Loving Highsmith review - documentary focused on the writer's lighter side | reviews, news & interviews

Loving Highsmith review - documentary focused on the writer's lighter side

Loving Highsmith review - documentary focused on the writer's lighter side

Eva Vitija presents a poignant portrait, but with most of the warts ignored

Since her death in 1995, Patricia Highsmith has prompted three biographies, screeds of often conflicting psychological analysis and now this documentary from the Swiss-born Eva Vitija. We hear the director say at the outset that by reading her then-unpublished diaries she learned to love, not just the writing, but the writer, which not all commentators have managed to do.

It’s tempting to say, "Join the queue, lady.” Highsmith was the most prolific of seducers, haunting gay bars around the world and specialising in pursuing married women. None of the relationships lasted, except for a couple that became friendships.

She passed time happily plotting how to kill her mother’s second husband

The most rewarding part of Loving Highsmith is the input of some of these ex-lovers, along with contributions from her Texan family. Two interviewees have died since the filming, so Vitija’s timing was spot on; and she narrowly missed being able to feature the mysterious “Caroline”, the married woman Highsmith moved to Suffolk to be near, who died just before Vitija located her.

These women still sound affectionate towards her, dark and difficult though she was. The writer Marijane Meaker (“MJ”), the last woman she shared a house with, even remembers Highsmith in the 1950s as unassuming, despite her fame. “She was easy to love.”

In Texas, her relatives are astounded to learn from Vitija that “Pat” numbered a distant family member among her conquests: “Aunt Milly”, who ran the American Airlines training programme for female air crew. The relatives fill in colourful background about the Coates family, Highsmith’s mother’s clan, who were, and still are, ranchers and rodeo announcers. Her grandmother, they reveal, wore her push-up bra and wig to bed her entire life. She was a “lady”, and granddaddy liked it that way.

Pat, though, was clearly a tomboy from the off, and there is a hilarious picture of her at about four years old in baggy shorts and big cap, legs planted in an A-shape, a cigarette in her mouth, doing her best Jackie Coogan impression.

With her now remarried mother, Mary, who had tried to abort her and abandoned her for the first six years of her life, she had a non-relationship, even after she moved to join her in New York. To MJ, Mary was a “bitch”, no love came back from her; yet Highsmith writes in a notebook: “I am married to my mother and will wed no other.” She also passed time happily plotting how to kill her mother’s second husband.

This acerbic relationship is usually regarded in Highsmith studies as the point of departure for understanding what drove her to become the solitary, hard-drinking writer of the blackest of stories, a predatory lover always looking to connect with a mother figure, though perhaps doomed to go on replaying being rejected by her. She dedicated two books to her mother, and kept secret her authorship of Carol until 1990, seemingly to protect her and the family from the controversy that would have followed.

The documentary has also had the benefit of access to Highsmith’s notebooks, finally published in 2021. These were written in French, German and Spanish, as well as English, and often had curses or warnings on their covers, to deter others from reading them. They contain many pronouncements about her approach to writing, how her books “poured out” of her, came from her bones, but also her insights into herself, a “forever-seeking” soul whose life was a “chronicle of unbelievable mistakes”.

The documentary has also had the benefit of access to Highsmith’s notebooks, finally published in 2021. These were written in French, German and Spanish, as well as English, and often had curses or warnings on their covers, to deter others from reading them. They contain many pronouncements about her approach to writing, how her books “poured out” of her, came from her bones, but also her insights into herself, a “forever-seeking” soul whose life was a “chronicle of unbelievable mistakes”.

Tax difficulties caused her to flee suddenly from her French village home to an ugly Swiss house she had built that a former French lover and lifelong friend, Monique Buffet, dubs “the bunker”. Vitija notes, with unseemly haste, that the diary entries dwindled and became vilely prejudiced – towards Jews, Arabs, all manner of foreigner – and racist. End of subject.

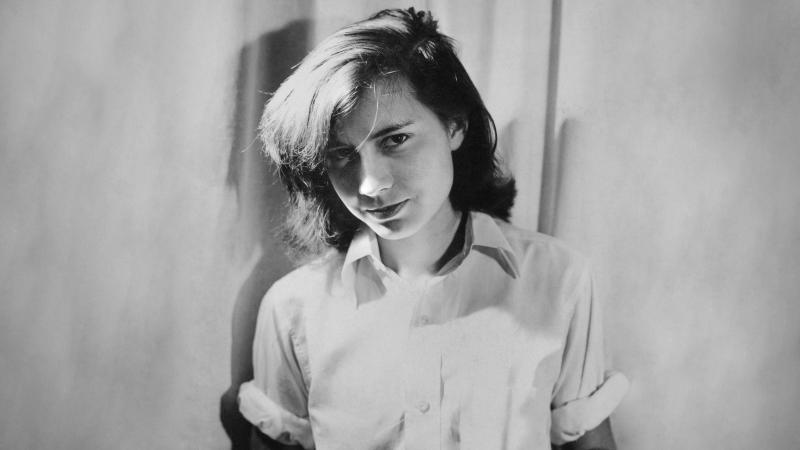

The film leaves us reflecting on the sad story of an unhappy, gifted woman who once went to Berlin transvestite bars that Bowie frequented, with the fabulous designer Tabea Blumenschein (pictured above), but ended up alone in Switzerland with her cats, slowly dying of leukaemia, yearning for the silence that triggered her subconscious, and thus her books.

But is this version any more satisfying than others that have sought to analyse Highsmith’s complex personality? Vitija’s lack of scrutiny of her anti-Semitism, for starters, is troubling. It had been a topic she reportedly pronounced on loudly in public long before, paradoxically, she had Jewish lovers. Was this anti-Semitism real, or part of an elaborate act to keep people at bay, an alternative persona (not unlike her grandmother’s, it has been said) that she carefully constructed around herself? Most commentators note the confluence of her life and her fiction: was her life-story also a construct, not just her writing?

It’s not a question Vitija even asks. She is more concerned to paint an evocative portrait of Highsmith’s personal life, which she succeeds in, with the to-camera interviews, montages of atmospheric photographs (including one of her nude), old footage of the rodeo gals she was supposed to emulate, all with a lilting country guitar soundtrack by Noel Akchote. Gwendoline Christie reads poignantly from the books and diaries, and Highsmith herself contributes via clips from interviews, some in her very American-sounding French. Carefully chosen clips from the films her texts inspired – Strangers on a Train, The Talented Mr Ripley, The American Friend, Carol – show the way her life bled into her work; Buffet suggests she was Ripley, a half-and-half person, like her beloved hermaphrodite snails.

But her anti-Semitism, the havoc she caused in people’s lives, even her tax problems in France, and especially the credibility of the pronouncements in her diaries: none of these is properly dug into. It’s like looking at a jigsaw with every third piece missing.

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

Add comment