In this juxtaposition of Piet Mondrian, a world famous modernist, and Hilma af Klint, a little known Swedish painter, guess who knocks your socks off ! This fascinating show is a delight and a revelation, because it declares the spiritualist underpinnings of modernism which many, until now, have sought to hide.

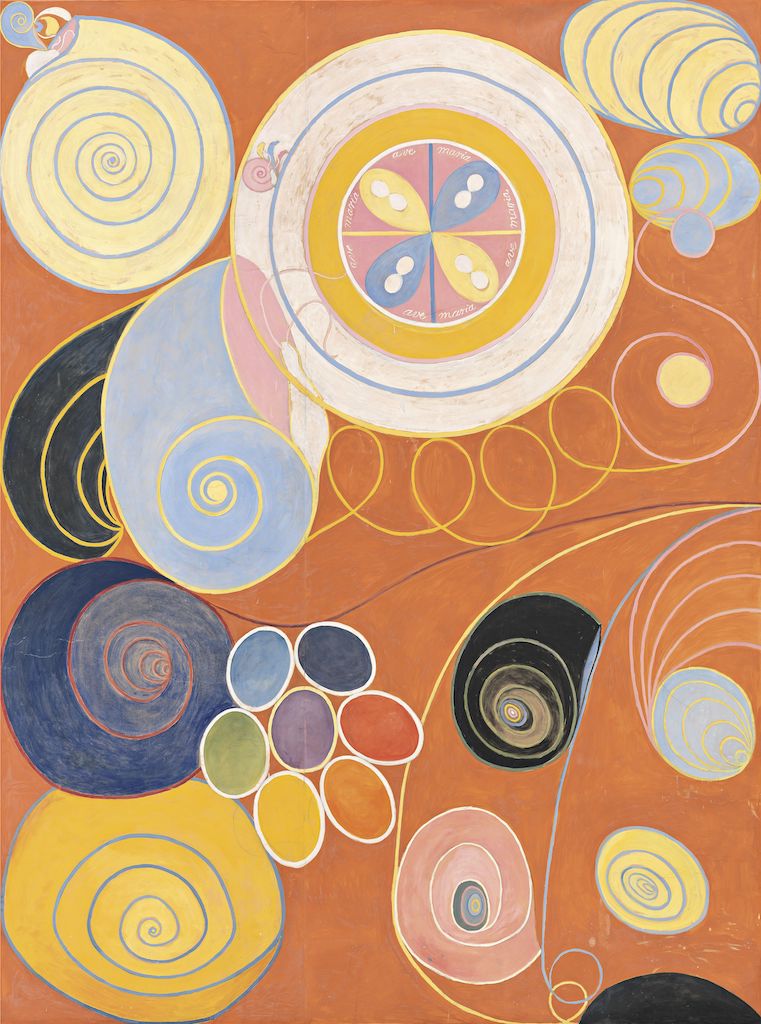

The exhibition comes to a climax in the very last room. Ten huge paintings – 10 foot by 8 – enfold you in the world of Hilma af Klint. The theme of this joyous installation is the progression from childhood to old age (pictured below: "Youth", 1907). Gliding across vibrantly coloured grounds, that vary from burnt orange to dark blues and soft pinks, are constellations of figurative and abstract shapes.

Roses and irises appear alongside leaves, shells, spirals, overlapping and concentric circles, curlicues and looping letter forms. It’s like gazing through a microscope and discovering a world of enormous beauty and calm where everything appears weightless – floating in a soup of benign well being. Af Klint’s paintings are far from just decorative. Nothing is random; in fact, the various elements constitute a kind of language. The subtext for The Ten Largest is the evolution of the human spirit; spirals represent that evolution and growth, while the almond shapes created by overlapping circles symbolise unity, the letters W and U stand for the material and the spiritual, O and A for alpha and omega, and so on.

Af Klint’s paintings are far from just decorative. Nothing is random; in fact, the various elements constitute a kind of language. The subtext for The Ten Largest is the evolution of the human spirit; spirals represent that evolution and growth, while the almond shapes created by overlapping circles symbolise unity, the letters W and U stand for the material and the spiritual, O and A for alpha and omega, and so on.

Af Klint was a mystic who took direction from a spirit guide named Amaliel. Under the guidance of this “High Master” she began the series in 1906, several years before Wassily Kandinsky – usually credited with producing the first abstract – had left figurative art behind. The series was intended to hang in The Temple, a spiral-shaped structure that existed only in the artist’s mind, and altogether this “commission” led to the creation of 193 glorious paintings, many of which are on show.

Af Klint’s mysticism was far from unusual. In fact, the pioneers of abstraction were all spiritualists. Like af Klint, Piet Mondrian – whose primary coloured paintings are the epitome of modernist abstraction – was a member of the Theosophical Society. This aspect of his work is usually down-played, because it embarrasses art historians. But Tate Modern’s juxtaposition of him with af Klint underlines the importance of Theosophical ideas to the evolution of abstraction.

A key belief outlined by Helena Blavatsky, Russian founder of the Theosophical Society, was the existence of invisible forces beyond surface appearances. The idea was backed up, of course, by recent scientific discoveries such as the presence of atoms, radio waves, electromagnetism and radiation – all invisible to the naked eye yet manifestly present – and X rays, which literally saw through the flesh to the structure beneath.

A key belief outlined by Helena Blavatsky, Russian founder of the Theosophical Society, was the existence of invisible forces beyond surface appearances. The idea was backed up, of course, by recent scientific discoveries such as the presence of atoms, radio waves, electromagnetism and radiation – all invisible to the naked eye yet manifestly present – and X rays, which literally saw through the flesh to the structure beneath.

Space, Blavatsky posited, was not empty but filled by ether, a medium through which radio waves etc could travel. And one of the most interesting rooms in the exhibition is devoted to the ether and associated concepts and the influence of such ideas on artists.

It explains how Theosophy sought to combine modern science with religion, philosophy, Darwin’s theory of evolution and ancient wisdom and thereby emphasise the interconnected of everything. I first encountered Theosophy in the 1970s, while writing a thesis about its influence on Kandinsky. Then it felt like esoteric nonsense, but aspects of it now seem rather perceptive. And importantly for art, Rudolf Steiner, head of the German branch of Theosophy, believed that artists could play a crucial role in revealing those hidden levels of reality.

“The form is the waves,” af Klint wrote, and “behind the form lies life itself.” In 1916 she painted a series of squares in unbelievably subtle watercolours, titled The Convolute of the Mental Plane, The Ether Convolute etc. It’s as if these exquisite abstracts are portraits of the very essence of being – pure spirit, the air, the ether, whatever you want to call it.

Both af Klint and Mondrian started out painting landscapes and flowers (pictured above left: Red Amaryllis with blue background, 1909–1910 by Piet Mondrian); af Klint’s delicate watercolours of wild flowers are especially delicious. Mondrian’s famous studies of an apple tree reveal his slow progress towards abstraction. Gradually the branches are reduced to a web of lines and curves, while the spaces between become increasingly dynamic; it’s as though he’s creating a dialogue between the visible and invisible, the tree and the enveloping ether. “Between the physical and the ethereal spheres there is a boundary, clearly delineated by the senses,” he wrote. “Yet the ether penetrates the physical sphere and acts upon it.”

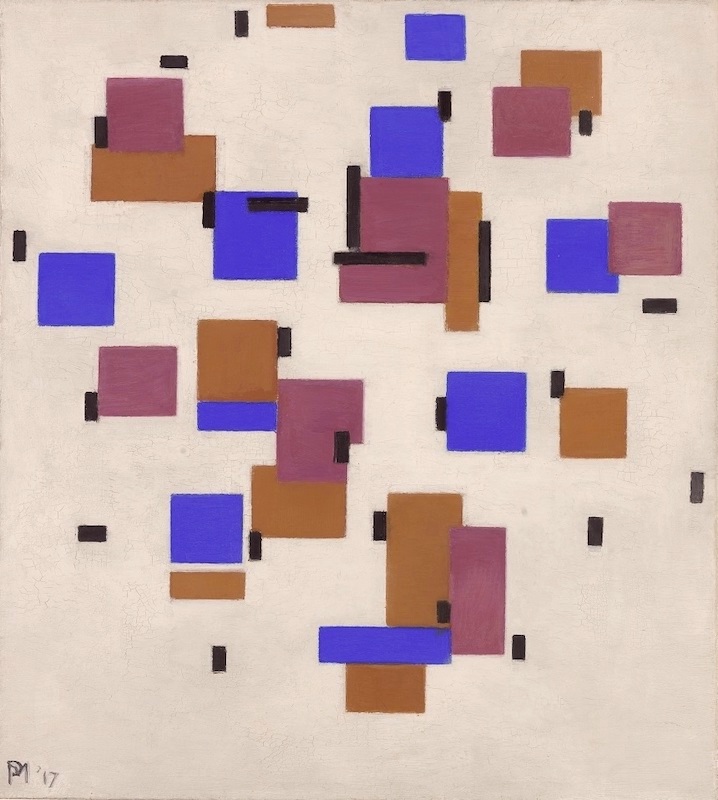

In 1911 he went off on a disastrous tangent, painting a triptych of three robotic females supposedly representing stages of enlightenment. It’s one of the worst paintings ever made. Luckily, that same year he came into contact with cubism, moved to Paris and developed the next phase – producing images in which the dialogue between lines and interstices makes no apparent reference to the external world (pictured right: Composition in colour B, 1917).

In 1911 he went off on a disastrous tangent, painting a triptych of three robotic females supposedly representing stages of enlightenment. It’s one of the worst paintings ever made. Luckily, that same year he came into contact with cubism, moved to Paris and developed the next phase – producing images in which the dialogue between lines and interstices makes no apparent reference to the external world (pictured right: Composition in colour B, 1917).

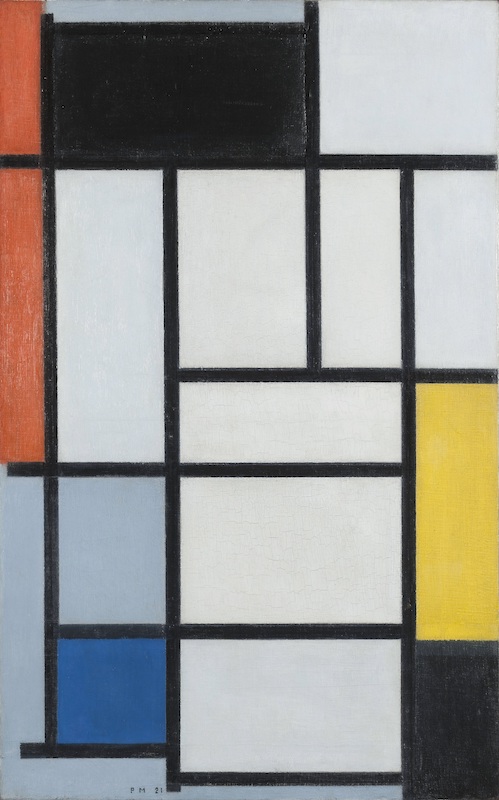

Finally he arrived at the signature style for which he is so famous – comprising a black grid in which the verticals represent the masculine or spiritual and the horizontals the feminine or material, with primary colours (red, yellow, blue) plus white or grey filling the rectangular spaces between. (Pictured below left: Composition with Red, Black, Yellow, Blue and Grey, 1921)

Mondrian’s progress towards abstraction was public, part of the unfolding story of modern art. Af Klint’s abstracts, on the other hand, were kept secret. While continuing to exhibit and sell her landscapes and portraits, she reserved her esoteric work for the eyes of fellow mystics. This was not from modesty but belief in their importance. “My mission, if it succeeds,” she wrote, “is of great significance to humankind. For I am able to describe the soul from the beginning of the spectacle of life to its end.”

Rudolf Steiner, from whom she sought approval, suggested that humanity was not ready for her radical visions so, when she died in 1944, she instructed her heirs to keep her esoteric work hidden for 20 years. For several decades after that, though, no-one took her seriously; her gender and mysticism both undermined her credibility.

But all that has changed. A solo show at the Modern Museum in Stockholm in 2013 put her on the map and her 2018 retrospective at New York’s Guggenheim Museum attracted a record 600,000 visitors.

But all that has changed. A solo show at the Modern Museum in Stockholm in 2013 put her on the map and her 2018 retrospective at New York’s Guggenheim Museum attracted a record 600,000 visitors.

It’s hard to look at the work of these two artists side by side; while af Klint’s paintings are still fresh and unfamiliar, over familiarity with Mondrian’s formulaic grids – especially their appearance on dresses, shoes and handbags – has rendered them about as exciting as lego.

Tate Modern’s show is rewriting and enriching the story of modern art. Not only does it establish af Klint as the first abstract painter, but by revealing how important spiritualism was to the pioneers of abstraction, it blows away the treasured belief that abstract art is pure form, devoid of content.

- Hilma af Klint & Piet Mondrian: Forms of Life is at Tate Modern until 3rd September

- More visual arts reviews on theartsdesk

![SEX MONEY RACE RELIGION [2016] by Gilbert and George. Installation shot of Gilbert & George 21ST CENTURY PICTURES Hayward Gallery](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_125_x_125_/public/mastimages/Gilbert%20%26%20George_%2021ST%20CENTURY%20PICTURES.%20SEX%20MONEY%20RACE%20RELIGION%20%5B2016%5D.%20Photo_%20Mark%20Blower.%20Courtesy%20of%20the%20Gilbert%20%26%20George%20and%20the%20Hayward%20Gallery._0.jpg?itok=3oW-Y84i)

Add comment