My Name Is Alfred Hitchcock review - a sly primer | reviews, news & interviews

My Name Is Alfred Hitchcock review - a sly primer

My Name Is Alfred Hitchcock review - a sly primer

The master of suspense surveys his cunning craft from beyond the grave

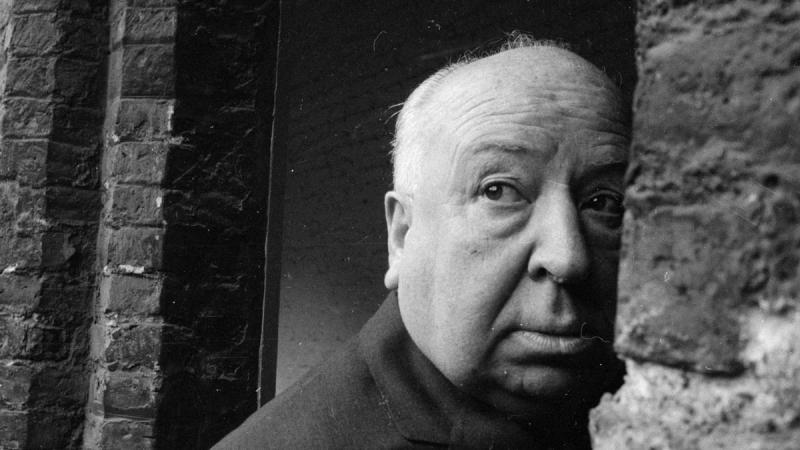

Mark Cousins pulled off a coup for his latest film history documentary, My Name Is Alfred Hitchcock, by getting the great director to narrate it. In his catarrhal East London drawl, Hitchcock parses dozens of the brilliant visual techniques he used to elicit emotional responses in his movies' audiences, as Cousins cuts rapidly from one memorable excerpt to another. Quite a feat since Hitchcock died 43 years ago.

The conceit mostly works well thanks to the unseen Alistair McGowan’s impersonation of Hitchcock. Insinuating and sardonic (not least in his fleeting observations about the speeded-up, 5G phone-distracted lives we live now), this Hitch makes us his confidants, his repeated rhetorical emphases – “Do you see?” “Don’t you think”? – building the intimacy. Not only an incisive critic, Cousins has a good ear: his Hitchcock monologue is as persuasive as McGowan’s mimicry.

The doc's playfulness is problematic, however – the irony not only palls over the two-hour running time but ultimately trivialises the film’s expert forensic analyses. Its yen to entertain undercuts the dark power and pathological complexity of Hitchcock’s oeuvre – the films’ under-scrutinized political alertness, their oneiric quality, the sadism behind the sexiness. Given his access to Hitchcock’s entire filmography, Cousins’ might have made a much more substantial documentary.

The doc's playfulness is problematic, however – the irony not only palls over the two-hour running time but ultimately trivialises the film’s expert forensic analyses. Its yen to entertain undercuts the dark power and pathological complexity of Hitchcock’s oeuvre – the films’ under-scrutinized political alertness, their oneiric quality, the sadism behind the sexiness. Given his access to Hitchcock’s entire filmography, Cousins’ might have made a much more substantial documentary.

The film is arranged in chapters themed to Hitchcockian preoccupations ( “escape”, “desire”, “loneliness”, ‘time”, “fulfilment”, and “height”). But the achronological arrangement of the clips chosen to demonstrate Hitchcock’s manipulations of images and sounds preclude Cousins showing how he evolved as a filmmaker over time. What was the source of his early virtuosity, as revealed in the British silents? Why did Hitchcock regard his 1934 The Man Who Knew Much (pictured above) as so much better than the 1956 one?

There’s an internal logic in the film’s organization, but for all of McGowan/Hitchcock’s deliberation as a commentator, the clips come too thick and fast, and are unhelpfully abstracted from the social or historical circumstances in which they were made. (An exception is Hitchcock’s contribution to the 1945 Holocaust documentary Memory of the Camps.) Brief interpolations filmed by Cousins – shots of an enigmatic young Asian woman, a black hand caressing a white back – feel like modish attempts to add a strain of contemporary multiculturalism.

Still, as a primer on the master’s ingenious methods, My Name Is Alfred Hitchcock is a treat. Cousins should be applauded for his discretion: in showing over and over again how Hitchcock creates and defies expectations in scenes, he never reveals the outcomes. Those viewers must discover for themselves – and many will.

rating

Explore topics

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Film

Steve review - educator in crisis

Cillian Murphy excels as a troubled headmaster working with delinquent boys

Steve review - educator in crisis

Cillian Murphy excels as a troubled headmaster working with delinquent boys

Can I get a Witness? review - time to die before you get old

Ann Marie Fleming directs Sandra Oh in dystopian fantasy that fails to ignite

Can I get a Witness? review - time to die before you get old

Ann Marie Fleming directs Sandra Oh in dystopian fantasy that fails to ignite

Happyend review - the kids are never alright

In this futuristic blackboard jungle everything is a bit too manicured

Happyend review - the kids are never alright

In this futuristic blackboard jungle everything is a bit too manicured

Robert Redford (1936-2025)

The star was more admired within the screen trade than by the critics

Robert Redford (1936-2025)

The star was more admired within the screen trade than by the critics

Blu-ray: The Sons of Great Bear

DEFA's first 'Red Western': a revisionist take on colonial expansion

Blu-ray: The Sons of Great Bear

DEFA's first 'Red Western': a revisionist take on colonial expansion

Spinal Tap II: The End Continues review - comedy rock band fails to revive past glories

Belated satirical sequel runs out of gas

Spinal Tap II: The End Continues review - comedy rock band fails to revive past glories

Belated satirical sequel runs out of gas

Downton Abbey: The Grand Finale review - an attemptedly elegiac final chapter haunted by its past

Noel Coward is a welcome visitor to the insular world of the hit series

Downton Abbey: The Grand Finale review - an attemptedly elegiac final chapter haunted by its past

Noel Coward is a welcome visitor to the insular world of the hit series

Islands review - sunshine noir serves an ace

Sam Riley is the holiday resort tennis pro in over his head

Islands review - sunshine noir serves an ace

Sam Riley is the holiday resort tennis pro in over his head

theartsdesk Q&A: actor Sam Riley on playing a washed-up loner in the thriller 'Islands'

The actor discusses his love of self-destructive characters and the problem with fame

theartsdesk Q&A: actor Sam Riley on playing a washed-up loner in the thriller 'Islands'

The actor discusses his love of self-destructive characters and the problem with fame

Honey Don’t! review - film noir in the bright sun

A Coen brother with a blood-simple gumshoe caper

Honey Don’t! review - film noir in the bright sun

A Coen brother with a blood-simple gumshoe caper

The Courageous review - Ophélia Kolb excels as a single mother on the edge

Jasmin Gordon's directorial debut features strong performances but leaves too much unexplained

The Courageous review - Ophélia Kolb excels as a single mother on the edge

Jasmin Gordon's directorial debut features strong performances but leaves too much unexplained

Add comment