A polar bear stands guard over the seal pup it has just killed (main picture). How could photographer, Hiroshi Sugimoto have got so close to a wild animal at such a dangerous moment? Even if he had a powerful telephoto lens, he’d be risking life and limb. And what a perfect shot! Every hair on the bear’s body is crystal clear; in fact, it looks as if her fur has just been washed and brushed.

Once you start peering more closely, other anomalies begin to emerge. The sea ice looks suspiciously like expanded polystyrene dusted with flour rather than snow, and the distant ice hills are clearly painted onto a backdrop. This is no wild life photograph, but a fabricated scene; and when he took the picture, Sugimoto was not standing on an ice sheet, but a wooden floor.

I don’t know if they are still on display in New York’s Natural History Museum, but I remember, on a visit to the Big Apple, being fascinated by the very dioramas that Sugimoto encountered when he moved to the city in 1974. Stuffed wolves, hyenas, vultures, monkeys and deer were among the animals posed in life-like positions surrounded by artificial grass, rocks and trees in front of painted backdrops that would fool nobody. Collectively, the experience felt apocalyptic – as if these dusty relics were all that was left of the wild life that once roamed the earth. Back then the idea wasn’t on anyone’s radar; now, though, it has become a hideous possibility.

I don’t know if they are still on display in New York’s Natural History Museum, but I remember, on a visit to the Big Apple, being fascinated by the very dioramas that Sugimoto encountered when he moved to the city in 1974. Stuffed wolves, hyenas, vultures, monkeys and deer were among the animals posed in life-like positions surrounded by artificial grass, rocks and trees in front of painted backdrops that would fool nobody. Collectively, the experience felt apocalyptic – as if these dusty relics were all that was left of the wild life that once roamed the earth. Back then the idea wasn’t on anyone’s radar; now, though, it has become a hideous possibility.

“My life as an artist began the moment I saw that I had succeeded in bringing the bear back to life on film,” says Sugimoto. Maybe if I hadn’t seen the dioramas in question, I might have been taken in by his series; but I don’t think so, because the scenes are too creepily static. Photography is not taxidermy; it may freeze a moment in time, but it’s never as lifeless as a stuffed creature. Contained within a photo of a living being somehow there’s a sense of continuity, of a future in which the subject carries on breathing and moving.

Sugimoto does something more important than breathe life into dead animals, though. He explores photography’s relationship both to reality and other forms of representation. This gives his work increasing resonance since, as our ability to tamper with photographs gets ever more sophisticated, the question of how we read and judge pictures becomes even more relevant.

There’s also a droll sense of humour at work. Some 20 years after taking the diorama pictures, he was at Madame Tussaud’s trying to breathe life into waxworks by photographing them individually against a black ground. And things get complicated, especially with historical figures like Henry VIII and Anne Boleyn that are based on oil paintings – official images, rather than actual likenesses – so humanising them means transforming an icon into a person. Dressed in finery that could have come from a dressing up box along with Woolworth’s finest buckles, rings and pearls, Henry VIII looks like an actor playing the part, while Queen Victoria could be a man in drag.

There’s also a droll sense of humour at work. Some 20 years after taking the diorama pictures, he was at Madame Tussaud’s trying to breathe life into waxworks by photographing them individually against a black ground. And things get complicated, especially with historical figures like Henry VIII and Anne Boleyn that are based on oil paintings – official images, rather than actual likenesses – so humanising them means transforming an icon into a person. Dressed in finery that could have come from a dressing up box along with Woolworth’s finest buckles, rings and pearls, Henry VIII looks like an actor playing the part, while Queen Victoria could be a man in drag.

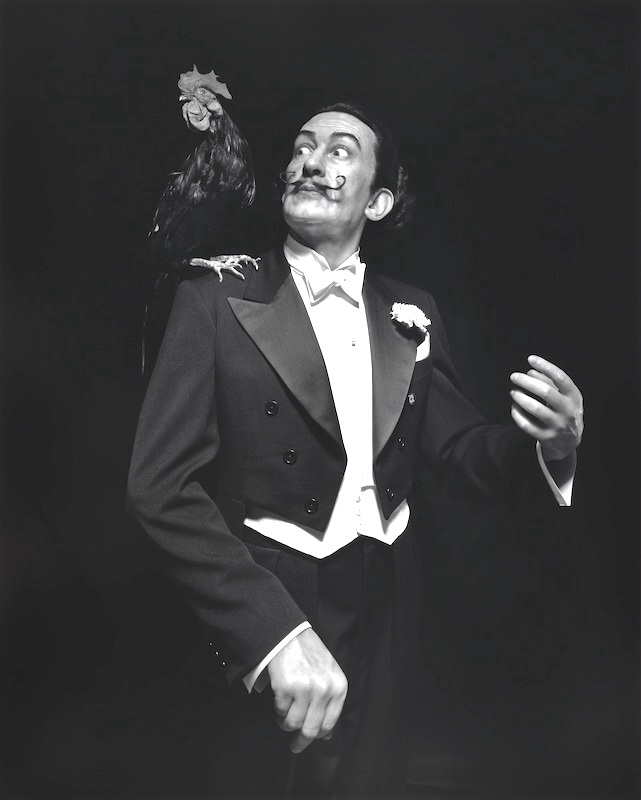

Even though she’s in full regalia, the late Queen seems to have been caught unawares; without the regal smile, she looks like a tired housewife in need of a break. Fidel Castro looks old and frail, and Napoleon appears introverted and unsure. Most convincingly theatrical is Salvador Dali, the consummate showman who was always playing a part (pictured above right), and most present is Princess Diana, probably because she’s wearing her own gown and is instantly recognisable to us as a photographic image.

The series, Theaters addresses the power of cinema (pictured above left: UA Playhouse, New York). “A two-hour film is the equivalent of 172,800 photographic after images,” Sugimoto points out, and he wants to record them all. By keeping the shutter open for the entire length of a feature, he captures the whole experience. The accumulated frames light up the screen with a white hot intensity. And casting an ethereal glow onto the surrounding architecture, seem to embody the emptiness of the promises offered by Hollywood. And when he projects a film inside a derelict cinema, theatre or opera house, the sorry sight of crumbling grandeur suggests misguided aspiration and broken dreams.

For over 40 years, Sugimoto used a traditional large format, wooden camera mounted on a tripod with black and white film, which he developed and printed himself. But in 2018 he began exploring colour. With the aid of a mirror and a huge prism that broke light up into its constituent parts, he was able to capture pure colour on film.

For over 40 years, Sugimoto used a traditional large format, wooden camera mounted on a tripod with black and white film, which he developed and printed himself. But in 2018 he began exploring colour. With the aid of a mirror and a huge prism that broke light up into its constituent parts, he was able to capture pure colour on film.

The resulting Opticks (pictured above right) are reminiscent of Mark Rothko’s abstract paintings, but if Sugimoto hopes to rival them he is on dangerous ground. Although beautiful, his images seem more like scientific experiments than paintings. If the life of a painting is visible in its surface – in the push and pull of the brush marks, for instance – the huge effort that went into making the photographs remains invisible. And missing the palpable history that gives a painting emotional resonance, they contain no sense of struggle, purpose or time.

Then there’s the annoyance of the reflections; a print shown behind glass that reflects people and gallery lights doesn’t allow one to experience pure colour. For that you need a light installation a la Dan Flavin.

But Sugimoto is wedded to his medium. The Seascapes which he began in 1980 and continues to this day (pictured below left: Bay of Sagami, Atami), are as much about the photographic print as they are about space, light and atmospherics. Gazing out to sea gives me a euphoric sense of infinite space unadulterated by human presence – a feeling of expansion almost akin to levitating.

By contrast, Sugimoto’s seascapes are almost claustrophobic in their flatness. Whether they were taken at night or by day, emphasis is on the horizon line that divides each photograph in half. There are no dramatic clouds or storm-tossed seas, no birds, boats or people – only uniform skies and oceans scarcely ruffled by tiny waves. So one’s eye is drawn to the differing textures of water and air, to the clarity or haziness of the dividing line between them and to the ability of a photograph to capture such nuances.

By contrast, Sugimoto’s seascapes are almost claustrophobic in their flatness. Whether they were taken at night or by day, emphasis is on the horizon line that divides each photograph in half. There are no dramatic clouds or storm-tossed seas, no birds, boats or people – only uniform skies and oceans scarcely ruffled by tiny waves. So one’s eye is drawn to the differing textures of water and air, to the clarity or haziness of the dividing line between them and to the ability of a photograph to capture such nuances.

The prints are hung in a progression from dark to light, which in reverse takes you from light into darkness. Sugimoto describes them as scenes that “are before human beings and after human beings”; not so much seascapes, then, as an opportunity to contemplate death, eternity or life on earth without humanity. It makes Sugimoto as much a philosopher as an artist and his seascapes more like icons than vistas. Pause for thought.

- Hiroshi Sugimoto at the Hayward Gallery until 7 January 2024

- More visual arts reviews on theartsdesk

![SEX MONEY RACE RELIGION [2016] by Gilbert and George. Installation shot of Gilbert & George 21ST CENTURY PICTURES Hayward Gallery](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_125_x_125_/public/mastimages/Gilbert%20%26%20George_%2021ST%20CENTURY%20PICTURES.%20SEX%20MONEY%20RACE%20RELIGION%20%5B2016%5D.%20Photo_%20Mark%20Blower.%20Courtesy%20of%20the%20Gilbert%20%26%20George%20and%20the%20Hayward%20Gallery._0.jpg?itok=3oW-Y84i)

Add comment