Thomas Adès: Alchymia Mark Simpson, Quatuor Diotima (Orchid Classics)

Thomas Adès: Alchymia Mark Simpson, Quatuor Diotima (Orchid Classics)

Thomas Adès continues to hit new heights of inventiveness in this new mini-album, a digital release of a mere 24 minutes. But there is no danger of feeling short-changed: Alchymia’s music is intense and dense, but also fluent and engrossing, demanding and rewarding multiple hearings. A four-movement piece for string quartet with basset-clarinet (an instrument usually only heard in Mozart’s Requiem) which, like his early string quartet Arcadiana examines a cultural idea from a range of perspectives, Alchymia is a panoramic and eclectic survey of the idea of alchemy.

The first movement, “A Sea-Change (…those are pearls…)” takes the simplest of descending motifs, the notes constantly dragged down as if to the watery depths, and plays complex rhythmic games with it, unrest gradually disturbing the placid surface. “The Woods So Wild” is based on Byrd, a moto perpetuo of fragile energy which resolves into an unexpected unison at its end. The “Lachrymae” references Dowland, finding something of his bleak beauty, while the finale, “Divisions on a Lute-Song: Wedekind’s Round” applies a typical Tudor structure (“division” form is a kind of evolving variation) to a piece of 20th century Expressionism. The result is as extraordinary as that description sounds. The music throughout is allusive and intriguing, as delicate as a carved walrus tusk but with complete conviction in every note. And it gets the performance it deserves from the remarkable Mark Simpson, whose playing is characterful and sensitive, finding charms and chills in Adès’s notes. The Quatuor Diotima make light of the technical challenges that Adès always presents to his interpreters, relaxing into the music and providing an ideal support for Simpson’s eloquent playing. Bernard Hughes

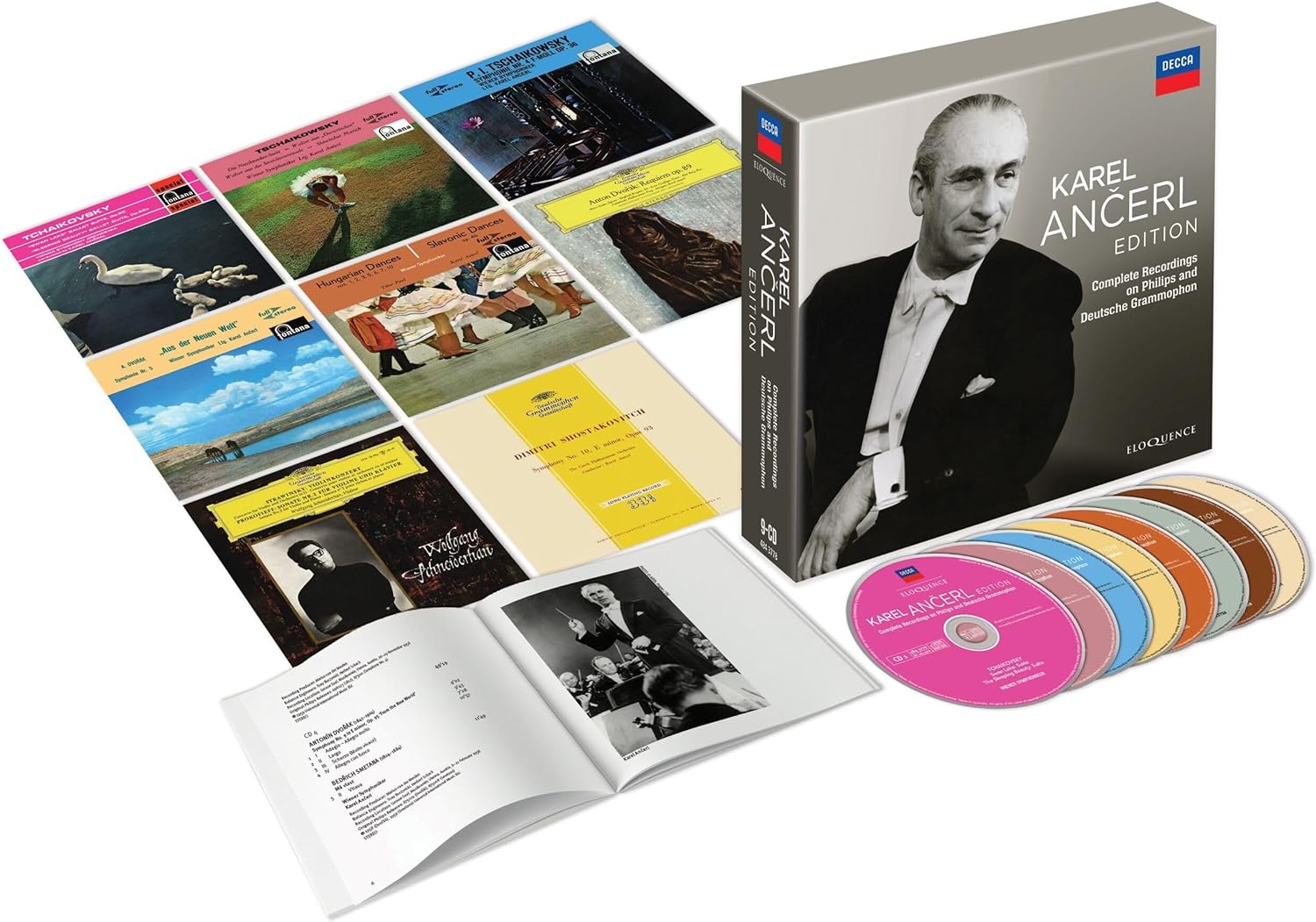

Karel Ančerl Edition: Complete recordings on Philips and Deutsche Grammophon (Decca Eloquence)

Karel Ančerl Edition: Complete recordings on Philips and Deutsche Grammophon (Decca Eloquence)

One thing that the world needs right now is a Supraphon box set containing all of Karel Ančerl’s recordings with the Czech Philharmonic. While we wait for that, get yourself a copy of Supraphon’s recent compilation of Ančerl’s live recordings, plus this Decca Eloquence set. Peter Quantrill’s booklet note outlines the difficulties which the conductor faced in post-war Prague, the Czech communist authorities describing Ančerl in a 1950 report as “a great individualist with bourgeois tendencies and manners”. Ten members of his orchestra acted as informers, and his phone was tapped before any foreign tours in case he was planning to defect.

Three famous DG recordings are included in this set, the most notable being a 1955 version of Shostakovich’s 10th Symphony with the Czech Philharmonic, only the work’s second appearance on disc. It’s a remarkable document, taped in Munich in clear mono sound, and one of the swiftest accounts on disc: Ančerl’s second movement lasts less than four minutes and is genuinely hair-raising. As is the finale, its mixture of exhilaration and terror brilliantly realised. Then there’s a 1959 co-production with Supraphon, the first recording of Dvořák's huge Requiem. Taped in Prague’s Rudolfinum in very good stereo, it boasts full-throated choral singing and excellent soloists. Sample the “Tuba mirum”, the passage where tenor Ernst Haefliger duets with a lonely oboe looking forward to Mahler. And do sample the “Confutatis”, where the men’s voices have incredible impact.

Three famous DG recordings are included in this set, the most notable being a 1955 version of Shostakovich’s 10th Symphony with the Czech Philharmonic, only the work’s second appearance on disc. It’s a remarkable document, taped in Munich in clear mono sound, and one of the swiftest accounts on disc: Ančerl’s second movement lasts less than four minutes and is genuinely hair-raising. As is the finale, its mixture of exhilaration and terror brilliantly realised. Then there’s a 1959 co-production with Supraphon, the first recording of Dvořák's huge Requiem. Taped in Prague’s Rudolfinum in very good stereo, it boasts full-throated choral singing and excellent soloists. Sample the “Tuba mirum”, the passage where tenor Ernst Haefliger duets with a lonely oboe looking forward to Mahler. And do sample the “Confutatis”, where the men’s voices have incredible impact.

Understandably, Ančerl was happy to accept conducting arrangements abroad, and his 1962 debut with the Berlin Philharmonic led to him recording Stravinsky’s Violin Concerto with Wolfgang Schneiderhan. This is still one of my go-to versions of a still-underappreciated piece, notable as much for the rhythmically alert orchestral playing (you can’t imagine these musicians having encountered the concerto before) as for Schneiderhan’s warm, witty playing. The original LP coupling is included, Schneiderhan and pianist Carl Seeman heard in Prokofiev’s Violin Sonata No. 2.

The remaining discs pair Ančerl with the Wiener Symphoniker. We get suites from the three Tchaikovsky ballets, Swan Lake especially good, and Ančerl’s 1812 Overture features some oddly balanced but spectacular bells. There’s an exciting Tchaikovsky 4th Symphony, almost but not quite approaching Mravinskian levels of hysteria, the Vienna players just about staying the course. A 1958 recording of Dvořák’s 9th isn’t as compelling as the 1961 Czech remake, but the brass playing is impressive. We get Smetana’s Vltava plus an entertaining disc coupling 8 Slavonic Dances with Tibor Paul's selection of seven Brahms Hungarian Dances. Decca Eloquence’s production values are predictably good, the sound handsomely remastered and the original LP sleeve art retained.

The remaining discs pair Ančerl with the Wiener Symphoniker. We get suites from the three Tchaikovsky ballets, Swan Lake especially good, and Ančerl’s 1812 Overture features some oddly balanced but spectacular bells. There’s an exciting Tchaikovsky 4th Symphony, almost but not quite approaching Mravinskian levels of hysteria, the Vienna players just about staying the course. A 1958 recording of Dvořák’s 9th isn’t as compelling as the 1961 Czech remake, but the brass playing is impressive. We get Smetana’s Vltava plus an entertaining disc coupling 8 Slavonic Dances with Tibor Paul's selection of seven Brahms Hungarian Dances. Decca Eloquence’s production values are predictably good, the sound handsomely remastered and the original LP sleeve art retained.

Maestro: Music by Leonard Bernstein London Symphony Orchestra/ Yannick Nézet-Séguin and Bradley Cooper (Deutsche Grammophon)

Maestro: Music by Leonard Bernstein London Symphony Orchestra/ Yannick Nézet-Séguin and Bradley Cooper (Deutsche Grammophon)

Anyone wanting to extend their listening of Bernstein – and Mahler, too, since I imagine the scene of the “Resurrection” Symphony’s closing stages in Ely Cathedral will inspire further investigation – will have to look elsewhere. This is exactly the music as it features in Bradley Cooper’s masterly film, with plenty of spoken dialogue too – but I like it. The only full tracks are those used as the credits roll – the UK’s sensational boy treble Malakai Bayoh in the central sequence of the Chichester Psalms (he also features in essential music from Mass) and the Candide Overture conducted by the film’s resident top conductor, Yannick Nézet-Séguin, a charismatic figure who might reach the kind of audiences Bernstein gained if times were different – and its most used orchestra, the London Symphony Orchestra, which had such an unforgettable relationship with Bernstein especially in the final years.

The orchestral tracks could be sharper soundwise, but the panache of Nézet-Séguin’s approach is never in doubt. And the contrasts of meditative, sometimes anguished, and punchy-brilliant work well as they do in the film. The American ensembles used are here, too, and it’s fun to revisit Shirley Ellis in “The Clapping Song”. Classy, like the masterly movie itself. David Nice

Fauré: Nocturnes and Barcarolles Mark-André Hamelin (piano) (Hyperion)

Fauré: Nocturnes and Barcarolles Mark-André Hamelin (piano) (Hyperion)

Fauré: Requiem and Messe des pêcheurs de Villerville La Chapelle Royale/Philippe Herreweghe (Harmonia Mundi)

I fell in love with the music of Gabriel Fauré when I was quite young, and my sense of fascination and delight has only grown over the years. I’ve covered quite a lot of Fauré recently, so how better to end the year with two recordings, a re-issued old classic and a new release which I have already come to value. Marc-André Hamelin’s Nocturnes and Barcarolles on Hyperion speaks to the ultra-refined, Gallic Fauré, the dreamy Fauré effortlessly spinning Chopinesque melodies and the muscular late-Romantic Fauré. But there is also the late Fauré, utterly unfashionable and battling deafness in his old age, creating peculiar and ineffable works like the B minor Nocturne op.119. Each of Fauré’s guises is inhabited effortlessly by Hamelin, the playing fluent and inventive. He is especially convincing in the passages, such as in op.37, where a simple texture gives way to flighty arabesque in the twinkling of an eye – and Fauré’s eye always has a twinkle in it.

His set of Barcarolles – “boat songs” – similarly span his whole career. No.2 has something of a Gershwin improvisation about it, and pre-echoes of Debussy’s Preludes, as does no.8. But again it is in the late pieces that real revelation is to be found: the final Barcarolle ploughs its own furrow, and Hamelin follows it down every byway. It is particularly revelatory when heard at the end of the sequence: a composer at the end of his long life delighting in finding new textures and dancing to nobody else’s tune. Definitely worth listening to as an album, not just isolated tracks.

Meanwhile a quick word on the Requiem in its 1988 recording by Philippe Herreweghe and La Chapelle Royale, recently re-released on Harmonia Mundi. This was a ground-breaking recording of the 1893 version, with its dark colours and omission of high strings, but was a bit of a disappointment. There is some sumptuous singing – Agnès Mellon’s “Pie Jesu” is ecstatic and pin-sharp – but the tempos are generally over-indulgent and sound is a bit washy (it isn’t clear if this re-issue is re-mastered: if it is, it hasn’t been a complete success). The “Agnus Dei” is great but overall I would recommend either Laurence Equilbey and the Orchestre National de France, or Tenebrae and the LSO, as better bets in the 1893 version.

Meanwhile a quick word on the Requiem in its 1988 recording by Philippe Herreweghe and La Chapelle Royale, recently re-released on Harmonia Mundi. This was a ground-breaking recording of the 1893 version, with its dark colours and omission of high strings, but was a bit of a disappointment. There is some sumptuous singing – Agnès Mellon’s “Pie Jesu” is ecstatic and pin-sharp – but the tempos are generally over-indulgent and sound is a bit washy (it isn’t clear if this re-issue is re-mastered: if it is, it hasn’t been a complete success). The “Agnus Dei” is great but overall I would recommend either Laurence Equilbey and the Orchestre National de France, or Tenebrae and the LSO, as better bets in the 1893 version.

Milhaud/ Tailleferre: Mélodies et Chansons Vol.2 Holger Falk (baritone), Steffen Schleiermacher (piano) (MDG)

Milhaud/ Tailleferre: Mélodies et Chansons Vol.2 Holger Falk (baritone), Steffen Schleiermacher (piano) (MDG)

Germaine Tailleferre is still in the process of becoming more than a footnote. The extensive compositional oeuvre of the only female member of Les Six really hasn’t been heard properly yet. For example, when France-Musique’s “En Pistes” programme featured “La Rue Chagrin” (1955) one of the Tailleferre songs from this album, both presenters had to admit to each other that they had never heard it before. The song in question, the most radio-friendly track from the new album by Holger Falk and Steffen Schleiermacher, is a slinky cabaret number with echoes of “These Foolish Things”, say, or the Schoenberg Brettl-Lieder. The words are by Denise Centore, from the time the pair were working together on five little pastiche/ parody operas for radio, “Du style galant au style méchant”. Their collaboration seems to have been a really successful one.

Tailleferre was prolific and hugely adaptable, and the selection of songs here, from the 1920s to the 1970’s shows that. “Six Chansons Franҫaises” are from 1929. A woman rails extensively against the men in her life always being the wrong ones (a bit incongruous hearing these songs being sung by a baritone). We also hear lively nonsense settings of Jean Tardieu, a poet who was the son of a lifelong friend; these songs are from much later in her life, 1977. There are some uncomfortable moments: I won’t be going back to the wordless Vocalise-Etude which starts in the falsetto register. As regards the selection here from Milhaud's vast song output, the most interesting set is the six Chansons Populaires Hebraiques, somewhere on the vast list of works written for Madeleine Grey - she also was also the dedicatee of works by Fauré, Ravel and Poulenc.

The main achievement here is that more of Tailleferre’s work is being given an airing. Hats off to Falk and Schleiermacher, and to MDG for making it happen. I hope that where a German baritone (born in Regensburg in 1972) has shown the way, French singers – Patricia Petitbon for the "Chansons Francaises", Stephane Degout for "La Rue Chagrin" please! - will follow. This review also led me in the direction of Falk’s Eisler discs which are an absolute revelation, with an incredible immediacy, authority, verbal clarity and breadth of stylistic nuance...which I don’t think the baritone can expect to match when he sings in French. Sebastian Scotney

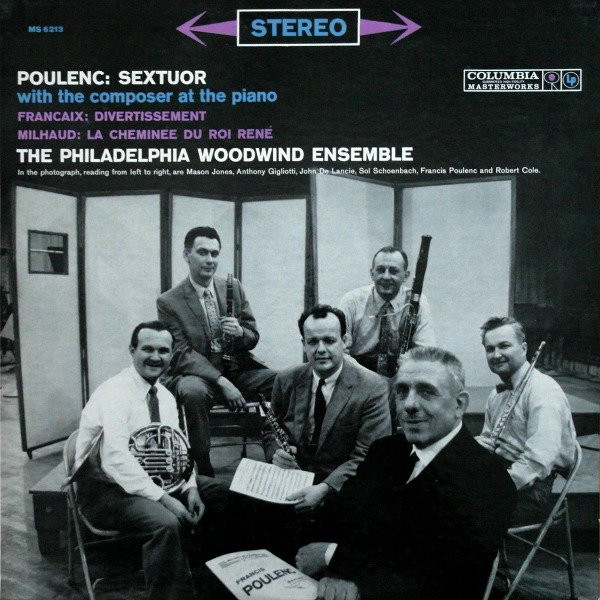

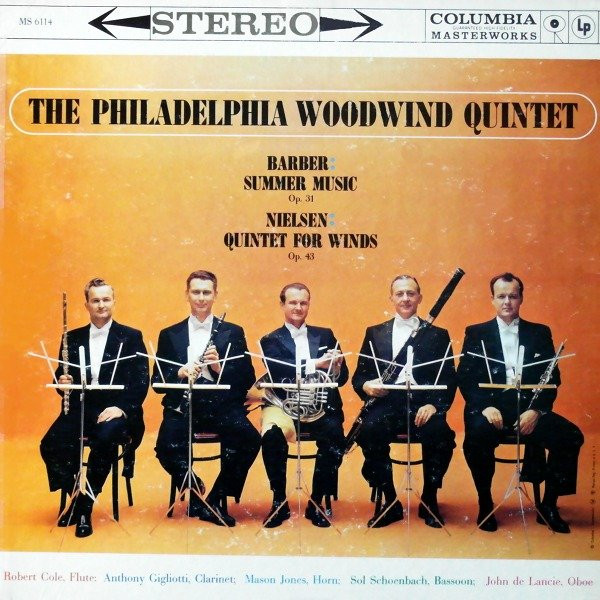

Philadelphia Woodwind Quintet: The Complete Columbia Album Collection (Sony)

Philadelphia Woodwind Quintet: The Complete Columbia Album Collection (Sony)

Filling 12 discs with wind quintets would be a tall order, so it’s understandable that many of the works contained in this superb box set are arrangements, works for smaller ensembles or quintets for winds with piano. The Philadelphia Woodwind Quintet began life in 1950 and released ten LPs between 1953 and 1968, its members the principal winds and horn of Eugene Ormandy’s Philadelphia Orchestra. It contained some starry names: hornist Mason Jones’s gutsy playing can be heard on Rostropovich’s first recording of the Shostakovich’s Cello Concerto No. 1, and oboist John de Lancie was the US Army corporal who, stationed near Richard Strauss’s home in the last days of WW2, suggested to the elderly composer that he write an oboe concerto.

There’s some fascinating repertoire here, including a delicious 1954 coupling of Janáček’s Mládí and Concertino (with pianist Rudolf Firkušný) – surely these pieces’ first non-Czech recordings? Both are superb, the players’ unhomogenised sound perfect for Janáček. Not that the playing isn’t the last word in terms of refinement; there’s something very Gallic about the way their individual colours blend. So, a 1960 recording of Poulenc’s Sextet, made with the composer, is one of the most idiomatic you’ll hear, and it’s coupled with some enticing Milhaud and Jean Françaix. Slightly more mainstream is a superb performance of Nielsen’s glorious Op. 43 Quintet. I love the composer’s own programme note, describing how “at one moment the players are all talking at once, at another they are quite alone”. The last movement’ solo variations are superb, and it’s oddly moving to hear the players reunited in the closing chorale.

There’s some fascinating repertoire here, including a delicious 1954 coupling of Janáček’s Mládí and Concertino (with pianist Rudolf Firkušný) – surely these pieces’ first non-Czech recordings? Both are superb, the players’ unhomogenised sound perfect for Janáček. Not that the playing isn’t the last word in terms of refinement; there’s something very Gallic about the way their individual colours blend. So, a 1960 recording of Poulenc’s Sextet, made with the composer, is one of the most idiomatic you’ll hear, and it’s coupled with some enticing Milhaud and Jean Françaix. Slightly more mainstream is a superb performance of Nielsen’s glorious Op. 43 Quintet. I love the composer’s own programme note, describing how “at one moment the players are all talking at once, at another they are quite alone”. The last movement’ solo variations are superb, and it’s oddly moving to hear the players reunited in the closing chorale.

We get two accounts of Mozart’s K452 Quintet, with Rudolf Serkin and Robert Casadeus (both great, especially the mono Serkin performance) and gems such as Hindemith’s witty Kleine Kammermusik and Jacques Ibert’s Trois Pièces brèves, notably zippier than an account included in Warner’s Dennis Brain box set. If you’re feeling brave, CD 4 contains a brave, pioneering account of Schoenberg’s Op. 26 Quintet, a piece that I can only tolerate in very small doses. It lasts 44 minutes - following it with the score (available on IMSLP) is worth doing, once, but this is a tough nut to crack.

We get two accounts of Mozart’s K452 Quintet, with Rudolf Serkin and Robert Casadeus (both great, especially the mono Serkin performance) and gems such as Hindemith’s witty Kleine Kammermusik and Jacques Ibert’s Trois Pièces brèves, notably zippier than an account included in Warner’s Dennis Brain box set. If you’re feeling brave, CD 4 contains a brave, pioneering account of Schoenberg’s Op. 26 Quintet, a piece that I can only tolerate in very small doses. It lasts 44 minutes - following it with the score (available on IMSLP) is worth doing, once, but this is a tough nut to crack.

It's good to hear the Philadelphians tackling a quintet by Anton Reicha, and arrangements of chamber works by Haydn, Mozart and Beethoven are fun. There’s an enjoyable album of transcriptions of Italian music and a disc titled Pastorale, containing Grainger, Stravinsky, Pierné and Jolivet. 5 Pieces for Wind and Percussion by Ernst Toch are worth hearing, paired with a string quartet by Henry Cowell. Oddest of all is the group’s last album, a 1967 anthology of works by jazz saxophonist Ornette Coleman. Initially forbidding, his Forms and Sounds is a grower, and hats off to the ensemble for tackling such outré music. Sony’s remasterings sound impressive, and it’s good to have the original sleeve designs (though you’ll need a magnifying glass to read the notes). A lovely box set, in other words – snap it up while you can.

Add comment