Expressionists: Kandinsky, Münter and the Blue Rider, Tate Modern review - a missed opportunity | reviews, news & interviews

Expressionists: Kandinsky, Münter and the Blue Rider, Tate Modern review - a missed opportunity

Expressionists: Kandinsky, Münter and the Blue Rider, Tate Modern review - a missed opportunity

Wonderful paintings, but only half the story

In 1903, Wassily Kandinsky painted a figure in a blue cloak galloping across a landscape on a white horse. Several years later the name of the painting, The Blue Rider (der Blaue Reiter) was adopted by a group of friends who joined forces to exhibit together and disseminate their ideas in a publication of the same name.

The key members were Kandinsky and his partner Gabriele Münter, Franz Marc, Marianne von Werefkin and her partner Alexej von Jawlensky, both Russian aristocrats. The group was based in Munich, but keen to emphasise their internationalism, they invited others to show with them, including French painters Robert Delaunay and Henri Rousseau.

Tate Modern’s exhibition of the Blue Rider has a similar emphasis; but the inclusion of artists peripheral to the group makes the introductory rooms feel rather turgid, despite the presence of some gorgeous paintings. Franz Marc’s 1906 portrait of his wife, Maria, for instance, is a subtle assemblage of greys, soft blues and creams while, at the other extreme, Marianne von Werefkin uses all the colours of the rainbow for a dramatic self-portrait (pictured right) in which she stares out through piercing red and turquoise eyes – ablaze with intensity.

Tate Modern’s exhibition of the Blue Rider has a similar emphasis; but the inclusion of artists peripheral to the group makes the introductory rooms feel rather turgid, despite the presence of some gorgeous paintings. Franz Marc’s 1906 portrait of his wife, Maria, for instance, is a subtle assemblage of greys, soft blues and creams while, at the other extreme, Marianne von Werefkin uses all the colours of the rainbow for a dramatic self-portrait (pictured right) in which she stares out through piercing red and turquoise eyes – ablaze with intensity.

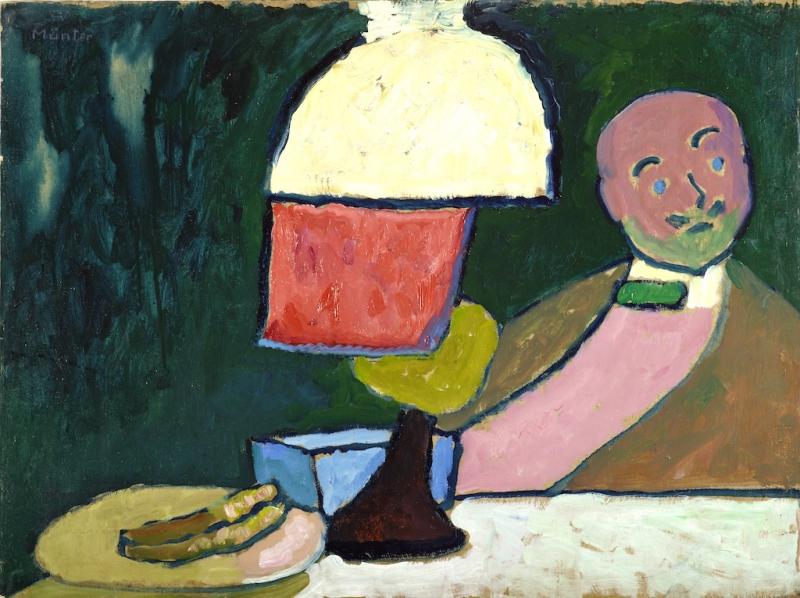

These influential artists deserve to be better known here and the women, who are too often excluded from history, are finally given their due. With their simplified forms, primary colours and black outlines, Gabriele Münter’s paintings are reminiscent of stained glass. Take, for example, her 1909 painting of Jawlensky listening to music (main picture); simple forms in striking colours are arranged on the diagonal to create dynamism in an otherwise static subject.

She portrays Werefkin as a force of nature rocketing skyward (pictured below left). With her oval face framed by a large hat and a magenta scarf draped over her pale turquoise blouse, she forms a dramatic pyramid silhouetted against an ochre ground.

That same year, Münter bought a house in Murnau, a small town nestling in the foothills of the Alps, which became a regular retreat for herself and her Russian companions. There Kandinsky began to experiment with abstraction, painting landscapes and street scenes that increasingly morph into swathes of bright colour articulated with black lines that suggest the presence of buildings, people and animals.

A woman sits milking a cow in a field edged with houses, a church and hills. The Cow 1910 (pictured left) is a joyous experiment in unifying the space by flattening everything into arcs and splodges of primary colour. The white cow is dappled with yellow and blue, the houses are white with green rooves while the hills become ribbons of blue and green.

A woman sits milking a cow in a field edged with houses, a church and hills. The Cow 1910 (pictured left) is a joyous experiment in unifying the space by flattening everything into arcs and splodges of primary colour. The white cow is dappled with yellow and blue, the houses are white with green rooves while the hills become ribbons of blue and green.

Meanwhile, Franz Marc was exploring the relationship between animals and the environment in paintings that suggest a profound sense of connection, which we humans have long since lost. Showing the influence of cubism, his glorious Tiger, 1912 (pictured below right) seems completely at one with surroundings that provide the strength for the animal to spring into action.

Ultimately, for Kandinsky, who had trained as a lawyer, experimenting freely was not enough. He was on a mission to save humanity from the slide into materialism, which he described as a black hand dragging humanity down. Painting was, he believed, a force for good that could impact the viewer directly – raising them to a higher spiritual level through a combination of forms and colours.

He studied the colour theories of Goethe and Chevreul and conducted experiments to arrive at what he considered a definitive understanding of the effects of different colours and shapes on the viewer. “Colour is the keyboard, the eyes are the hammers, the soul is the strings,” he wrote in his seminal essay The Art of Spiritual Harmony 1914. “The artist is the hand which plays, touching one key or another to cause vibrations of the soul.” It was incumbent on him, then, to develop an abstract language that had validity – based on what he called “inner necessity”. For many years, this belief was the driving force behind his work. Students at the Bauhaus, where he later taught, even nicknamed him Herr Gott because of this conviction !

He studied the colour theories of Goethe and Chevreul and conducted experiments to arrive at what he considered a definitive understanding of the effects of different colours and shapes on the viewer. “Colour is the keyboard, the eyes are the hammers, the soul is the strings,” he wrote in his seminal essay The Art of Spiritual Harmony 1914. “The artist is the hand which plays, touching one key or another to cause vibrations of the soul.” It was incumbent on him, then, to develop an abstract language that had validity – based on what he called “inner necessity”. For many years, this belief was the driving force behind his work. Students at the Bauhaus, where he later taught, even nicknamed him Herr Gott because of this conviction !

In the show, though, it is glossed over with scarcely a mention; likewise his interest in the spiritualism of Theosophist Annie Besant and Anthroposophist Rudolf Steiner. Theosophist CW Leadbeater claimed to see coloured shapes emanating from people as indicators of emotional states. Watercolours of these “thought forms” include those of an audience listening to Wagner and it’s no coincidence that, in his painting “Impression III, Concert” 1911, Kandinsky uses similar patches of colour to portray an audience’s response to the atonal music of Arnold Schoenberg. The painting is on show, but there’s no mention of this crucial connection.

Kandinsky was synthesthetic – listening to music prompted him to see colours and, conversely, colours were associated with various instruments. He began working on a stage production featuring yellow giants and “vague red creatures” moving to music. Yellow Sound was to be performed in Munich, but the outbreak of World War I put paid to the plan, but it has since been performed (and filmed) several times. A whole room is devoted to Werefkin’s support for performer Alexander Sacharoff, so why no record of Kandinsky’s pioneering work?

Many of the paintings Kandinsky titled Impression or Improvisation are based on biblical stories like the Apocalypse, Last Judgement and Flood and religious themes such as All Saints Day and St George slaying the dragon. These glorious canvases are among the most dynamic, exhilarating and beautiful pictures ever made; here, though, they’re hung on walls painted charcoal grey, which absorbs the light and sucks the life out of the colours. And no mention is made of their apocryphal subject matter, which many see as a portent of the war soon to engulf Europe but, for Kandinsky, was indicative of a general spiritual malaise.

Many of the paintings Kandinsky titled Impression or Improvisation are based on biblical stories like the Apocalypse, Last Judgement and Flood and religious themes such as All Saints Day and St George slaying the dragon. These glorious canvases are among the most dynamic, exhilarating and beautiful pictures ever made; here, though, they’re hung on walls painted charcoal grey, which absorbs the light and sucks the life out of the colours. And no mention is made of their apocryphal subject matter, which many see as a portent of the war soon to engulf Europe but, for Kandinsky, was indicative of a general spiritual malaise.

Based on the theme of the Flood, Improvisation Gorge 1914 is filled with depictions of gushing water and people desperately trying to navigate the deluge in boats (pictured below: Improvisation Deluge 1913). The painting is hung in a room lit by a loop of changing wavelengths that subtly alter the pigments from glowing crimsons, ochres and blues to a palette of sickly hues. Olafur Eliasson is responsible for this astoundingly arrogant act of aggression against an artist for whom colour was an all-important medium of communication.

For the curators to include this assault shows an amazing lack of understanding of the other work on show. While providing the opportunity for us to see these wonderful paintings, at the same time, Tate Modern seems to be doing its best to dilute their meaning. And given that the work of Franz Marc and von Werefkin has a comparably spiritual bent, this is to seriously misrepresent the Blue Rider project. The role of the curator is surely to respect the past, not to reinvent it to suit their own agenda. As an atheist, Kandinsky’s spiritualism does nothing for me, but to appreciate his paintings you need to understand the ideas that motivated them. What we need now is a proper retrospective of his work including the beliefs and sources which inspired him – no matter how misguided or overblown they may seem today.

The role of the curator is surely to respect the past, not to reinvent it to suit their own agenda. As an atheist, Kandinsky’s spiritualism does nothing for me, but to appreciate his paintings you need to understand the ideas that motivated them. What we need now is a proper retrospective of his work including the beliefs and sources which inspired him – no matter how misguided or overblown they may seem today.

rating

Buy

Explore topics

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Visual arts

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

Lee Miller, Tate Britain review - an extraordinary career that remains an enigma

Fashion photographer, artist or war reporter; will the real Lee Miller please step forward?

Lee Miller, Tate Britain review - an extraordinary career that remains an enigma

Fashion photographer, artist or war reporter; will the real Lee Miller please step forward?

Kerry James Marshall: The Histories, Royal Academy review - a triumphant celebration of blackness

Room after room of glorious paintings

Kerry James Marshall: The Histories, Royal Academy review - a triumphant celebration of blackness

Room after room of glorious paintings

Folkestone Triennial 2025 - landscape, seascape, art lovers' escape

Locally rooted festival brings home many but not all global concerns

Folkestone Triennial 2025 - landscape, seascape, art lovers' escape

Locally rooted festival brings home many but not all global concerns

Sir Brian Clarke (1953-2025) - a personal tribute

Remembering an artist with a gift for the transcendent

Sir Brian Clarke (1953-2025) - a personal tribute

Remembering an artist with a gift for the transcendent

Emily Kam Kngwarray, Tate Modern review - glimpses of another world

Pictures that are an affirmation of belonging

Emily Kam Kngwarray, Tate Modern review - glimpses of another world

Pictures that are an affirmation of belonging

Kiefer / Van Gogh, Royal Academy review - a pairing of opposites

Small scale intensity meets large scale melodrama

Kiefer / Van Gogh, Royal Academy review - a pairing of opposites

Small scale intensity meets large scale melodrama

Jenny Saville: The Anatomy of Painting, National Portrait Gallery review - a protégé losing her way

A brilliant painter in search of a worthwhile subject

Jenny Saville: The Anatomy of Painting, National Portrait Gallery review - a protégé losing her way

A brilliant painter in search of a worthwhile subject

Abstract Erotic, Courtauld Gallery review - sculpture that is sensuous, funny and subversive

Testing the boundaries of good taste, and winning

Abstract Erotic, Courtauld Gallery review - sculpture that is sensuous, funny and subversive

Testing the boundaries of good taste, and winning

Edward Burra, Tate Britain review - watercolour made mainstream

Social satire with a nasty bite

Edward Burra, Tate Britain review - watercolour made mainstream

Social satire with a nasty bite

Ithell Colquhoun, Tate Britain review - revelations of a weird and wonderful world

Emanations from the unconscious

Ithell Colquhoun, Tate Britain review - revelations of a weird and wonderful world

Emanations from the unconscious

Rachel Jones: Gated Canyons, Dulwich Picture Gallery review - teeth with a real bite

Mouths have never looked so good

Rachel Jones: Gated Canyons, Dulwich Picture Gallery review - teeth with a real bite

Mouths have never looked so good

Add comment