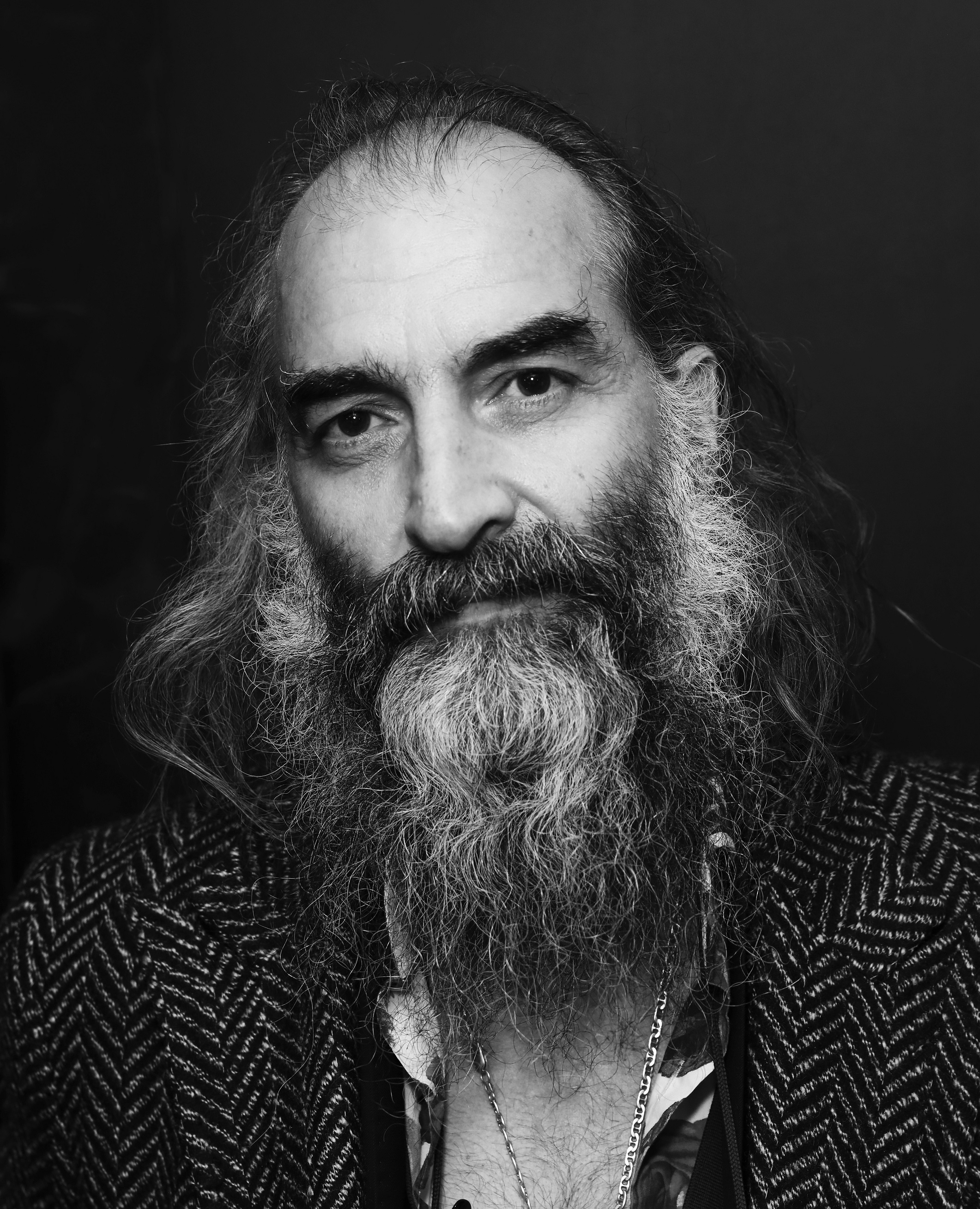

Warren Ellis is Nick Cave’s wild-maned Bad Seeds right-hand man and The Dirty Three’s frenzied violinist. Justin Kurzel’s Australian film subjects meanwhile exist on the malign edge, from Snowtown’s suburban serial killer and Nitram’s mass shooter to Ned Kelly.

Ellis is the contrastingly loving renegade subject of Kurzel’s debut documentary Ellis Park, an escapee from suburban Ballarat who here journeys further out to the titular Sumatran wildlife sanctuary he helps fund, where he plays to animals like a shaman Dolittle in jungle mist.

Ellis Park divides halfway between Ellis’s reluctant return to Ballarat and his subsequent sanctuary visit. Skittish time back at his family home with mum and dad John, a beautiful 89-year-old who literally packed up his musical hopes in a box upon starting a family but “demystified” art for Warren, is a haunting heartbreaker by itself, with John’s ancient, gentle smile and watchful dignity a human wonder. Home is also where Warren and his brother saw the garden illuminated with a midnight display of capering clowns, a childhood hallucination or revelation which sparked an open-hearted life.

Kurzel escorts Ellis to Ballarat sites of junkie purgatory and peaceful sanctuary during troubled early years. He plays violin beneath a park statue of a Pompeii family fleeing Vesuvius, the mother hopelessly shielding her baby with a sheet. The scene’s importance became clear to Kurzel later. “I didn’t fully appreciate what that sculpture was, with the element to it of maternity and protection. I didn't quite see at first that a lot of the [animal] park is about that, and it wasn’t until the edit that I started to feel these guardian angels over violence. With some of my films, it's been about why violence happens. Now it was the hope and care and love and rehabilitation after violent acts that really moved me. I’m definitely moving towards the light.”

Kurzel escorts Ellis to Ballarat sites of junkie purgatory and peaceful sanctuary during troubled early years. He plays violin beneath a park statue of a Pompeii family fleeing Vesuvius, the mother hopelessly shielding her baby with a sheet. The scene’s importance became clear to Kurzel later. “I didn’t fully appreciate what that sculpture was, with the element to it of maternity and protection. I didn't quite see at first that a lot of the [animal] park is about that, and it wasn’t until the edit that I started to feel these guardian angels over violence. With some of my films, it's been about why violence happens. Now it was the hope and care and love and rehabilitation after violent acts that really moved me. I’m definitely moving towards the light.”

Ellis Park’s second half shows Femke den Haas working at her Sumatra Wildlife Center and Ellis Park Wildlife Sanctuary, and Ellis recording the mantric, roaring soundtrack while experiencing the horror of human violence to animals, and den Haas’s team’s calling to heal them. Her partner Benfika’s tearful memory of resisting the death of double amputee monkey Rina is rewarded by Rina’s dexterous survival and charismatic eyes peering at Kurzel’s camera. The release of exploited monkeys to the wild as Ellis’s speeding bike nearly levitates back home in Paris and Nina Simone sings “I Wish I Knew How It Would Feel To Be Free” is ecstatic cinema.

Here Ellis speaks to The Arts Desk from his London home about how making this deeply felt, transcendent film broke him, then saved him.

NICK HASTED: What’s your relationship with the film now?

WARREN ELLIS: It became an incredibly important creative process and exorcism for me as a human being. I haven’t watched it since a screening in Melbourne with 1000 people, and it was one of the worst experiences of my life. I had to talk afterwards, and I could barely string a sentence together because it made me incredibly emotional, seeing myself back in that time and place. It caused a lot of upset within my family, all linked to the family stuff that I was discussing in the film [including Ellis’s mum’s abuse of his dad]. One of my brothers is still incredibly upset about it to this day. My older brother, who I’d been estranged from for 40 years, wasn’t upset, and we’ve reconnected, and that was a really beautiful thing that the film gave me. Making the film was to raise awareness and shine a light on the people [at the sanctuary], it wasn’t a vanity project, I didn’t even want it to be about me. I said to Justin, “Why the fuck are we going to Ballarat?” He said, “We have to try to tell people who you are, and why you might’ve [financed the sanctuary].” But for me it raised a lot of problems. I had a very difficult relationship with my mother. At one point, I tried to pull the film. I told Justin and he said to me, “Look, we can stop it now. I would encourage you to see this through. I’ll leave the camera running, and I promise you will have a say at the end as to what goes in.” I went from barely knowing Justin to him being one of the most important collaborators I’ve worked with, on one of the most important experiences. I know I did the right thing releasing it.

Sumatra was one of the most beautiful and extraordinary experiences of my life. I’d been in the jungle, waking up to the sound of the animals in morning. I went over there to make a film about monkeys and primates, and realised how extraordinary people are, when we put our best foot forward. It was almost like taking mushrooms and the [high] that drugs can stimulate in you. And when I got back I think it was inevitable that I collapsed, because I hadn’t really had time [to process it], then I was doing the Australian Carnage tour [with Cave], I was making this film, I spent a month with my dad as he was dying, I had a prostate issue, a new girlfriend [after separating from his wife], all this life shit, just when everything seemed to be falling into place. In the six months in between the demos for Wild God and then going in the studio with the Bad Seeds, I had a breakdown. It’s happened to me several times before throughout my life, it’s my body saying, we’re taking you out for a while, you can’t go on like this, and the filming definitely amplified it. I’d also just jumped off taking benzodiazepine for anxiety after 12 years, which was worse than when I jumped off heroin, worse than alcohol. That also had ramifications, and I went down a wormhole. If I’ve got something to do, that’s my anchor. But I’d finished all my work, I was left to own devices, and generally what happens to me then can be quite alarming. I’ve been like that all my life.

You went so high without preparation in Sumatra, then all the struts were knocked out when you got back.

It also demanded that I stay honest to my concept of the creative process. The film was on my mind all through these difficulties, if I stopped it coming out I was accountable for its funding, at one point for $5 million I didn’t have. It never got to that, but I was getting in the way of a director’s vision. I’ve seen this on so other many films, and I called Justin and said, “Make the film you want to make.” Justin said to me when it was finished and we were having a drink, “I pushed you as hard as any actor I’ve ever pushed.” I said, “Thanks, I appreciate that.” He had the book as a touchstone of what to put in, there was a loose narrative but we shot so much stuff and it was all found in the edit. He was really running by his instincts, and he came up with this idea for me to play music in all the places I felt safe in as kid. It allowed me to reclaim these places on my own terms, as the adult person I’ve become. Justin knew how to be gentle with me, but also how to push me, and try to help me walk through it.

There was a human responsibility for both of you, working in such tender terrain.

I could only have done this with an Australian. Justin had similar experiences growing up in a little town. I was able to be transparent with him, and he didn’t want to hurt anybody. There was a lot more that he could have put in that he didn’t.

I loved Snowtown, and I’ve seen all his films. Justin’s a really great director and extraordinary human being, and fundamentally Australian. There’s something in Australians of a certain generation - Justin’s a little bit younger than me, and I see this in Nick, Andrew [Dominik, whose films include several Cave documentaries featuring Ellis], and the guys in Dirty Three. When we were younger we didn’t aspire to be doctors or lawyers. We aspired to be creative people, the highest thing for me was the books on my shelf and the records and the films I went to see, this was the most important stuff in life. Justin has this too. Australians, we’re kind of raw and Australian stuff when it’s working at its best its poetic, it has a sense of humour, it’s chaotic, it’s irreverent, but there’s always this fundamental belief in the creative act that you’re going into, and after I did this, I realised all the people I have significant creative relationships with are Australians. Nick is the most important collaborator in my life, for the last 30 years we’ve chipped away at a relationship that’s only based on advancing, and when that doesn’t happen, it’s over. I have a brotherly kinship with Andrew. I do consider Femke [den Haas, the Dutch creator of the Sumatra Wildlife Center and Ellis Park] is an important person I’m having a creative relationship with.

I just watched The Narrow Road to the Far North, and I felt the same way as I did at the end of Ellis Park. There’s another great, purging emotional rush - not to compare your life to Narrow Road’s doctor in a Japanese POW camp…

Well, a lot of us have quite spectacular lives but you just don’t hear about it, we’re all going to battle daily with ourself. You just never know what’s going on with people. For me Ellis Park is about such fundamentally human things, which is why I wanted it to come out.

She was so true, she was such a pure person, and her motives weren’t clouded. She’d seen an injustice done to the animals, she’d gone over there and seen an orangutan chained up, she’d seen the skin and bone around the chain, and had it released. She just rolls up her sleeves and does what’s needed, all the people at the Center are like that.

In the film you say Nina Simone’s gum represents our imagination and what we’re capable of doing.

It felt like the heart of an idea. To me the gum is a metaphor. [Simone’s performance] is a beautiful thing that I witnessed, but the chewing gum and the story I wrote is about other people who become connected to this idea that it is her chewing gum that I’ve had for 20 years, and that I care about it. A friend summed it up when she said it was like the hair of Christ, and Andrew Dominik said, “Would you ever mass produce them? It could become the next crucifix.” These are such beautiful leaps of faith to make.

You share with Nick not an unquestioning faith, but a happy belief in there being more than the rational in the world.

I believe in something, and I need that in order to take a leap of faith. I feel like as a creative person or just as a human being, if you look at it in a logical way, it shuts down such an extraordinary universe, which is the imagination.

You’ve been centre-stage with the book and then this film. Are you out of your comfort zone?

Well, with Dirty Three I’m very much centre-stage, but there aren’t any words and that was great, because we just let it rip. Compared with the stuff with Nick, the drive with the film was coming from me and the Park. That was a new-found responsibility.

One important Australian in the film is your dad. There’s a moment when he’s on the sofa talking about the clowns you and your brother saw in your garden as kids, and he says he’s all for amazing, unbelievable visions. Is part of his importance in your childhood that he had that openness to something bigger?

My dad was straight-up, he was a mechanic, a really creative guy, he had a family he had to take care of, but he never lost his dream. That summed him up when he says, “Who am I to question somebody, if it happened it happened.” I realised when I got older that my dad was quite a special character. His dreams to be a singer were shut down, but he always encouraged ours. The making of this was extraordinary with my dad in particular, because my mum had advanced dementia, he had a big cancer on his face. I spent a month looking after him after the first operation, and he said to me, “Well, this is pretty shit, but the great thing is I’ve got to know my son in a way I never would’ve.” He goes, “I’ve watched you and I’ve been so proud of you” - and he looks at me, and I’m up to my elbows in the fucking toilet. “But now after all that, if you’ll come back and clean your dad’s toilet, I can see the sort of man that you’ve become.” I don’t say that in a sentimental way, but this film has provided me with experiences that I will remember for ever, that wouldn’t have happened otherwise.

The film’s Australian and Sumatran halves connect when you say of the places where you played music growing up that you were “trying to create a place of peace, and a place to feel safe”. Did your own vulnerability and need for sanctuary connect to your empathy with the animals?

It’s not something I would have thought of, but the narrative would suggest that. I think Justin was right when he said, “I think the reason you did this is back there.” When he asked me places I liked and I mentioned the statue of Pompeii [with a mother shielding her child from the lava, “Doing what you could in a situation,” Ellis says in the film, “doing your best”], it wasn’t for narrative reasons, it was just one of the first, real places I thought of. So it was quite something to see him and the editors’ idea of what was going on while we were filming. Maybe what you’re saying is what they’re hinting at. It’s really weird, because I could never have talked to you about all this, so the idea of having a fucking camera on me and talking about it almost shut me down. The upside of it is when you share this stuff, the load becomes lighter. I always felt a sense of guilt or shame. I’ve been doing therapy for various reasons, I’ve been in primal scream therapy, I’m still an addict. I function at a high level in the musical world. But I’m basically human, and [we should be] encouraged to share this stuff more. I’ve seen in AA meetings where people are able to speak so clearly about themselves. I’d always been quite shut down on certain things, and open book on others. My mother was a complex woman, it was interesting that when people watch it they feel empathy for her, as opposed to thinking she’s the monster in the story, which she wasn’t. My mother was subject to violence from her mother, it was passed on, till you’re able to take a step back and say, “No more.” My mum was the most charitable person I knew. I’ve had some of my best conversations about this film, because it’s like an open door. When people see the vulnerability, they expose their own as well. And these days I find that so important, because I want life to have meaning.

All the music is recorded as it’s being filmed, even in the studio, Justin didn’t want a traditional score, so it was intrinsically linked to the image and narrative. I started some of those ideas in the bottom of a monkey cage. I met musicians and traditional dancers and we were jamming ideas that kept evolving, I met a kid on a beach and we started playing their idea, and none of that was used. Then nine months after, Justin said, “I think it would be good go in the studio and evolve this.”

Does music strike you any differently at the bottom of a monkey cage?

No, place doesn’t do anything for me. At the weekend I played probably the greatest show I’ve ever played in my life in Sicily. I played the sun-up, and there was a lightning storm, and I knew it had started, but I didn’t see any of it. I’ve seen footage, and you’d think I was playing [the storm]. When I yell, the lightning happens, but I had no idea this was going on. Which is a great first lesson when making music to film, don’t look at the image, because the beautiful accidents are majestic when they happen. But I could have been at the bottom of a monkey cage then. The only place that matters, when I’m onstage or in the studio is here [pointing at self]. The only thing I know is when I’m unable to access that space, I’m quite fucked up, and I know my safe haven is no longer safe. Music is something I was just doing all my life and I didn’t realise I was building this place, that was like a structure. When I started doing TM, it’s identical to when I’m playing music. Everything stops. I’m just at one with myself, and nothing comes into that. I could be in the best studio in the world or the shittiest little garage. The only place that’s important is in me. I look around in Sumatra and I’ve got a meerkat running over me, and a monkey took a swing at me and I held up my violin to protect myself, but most of the time I’m unaware. The place that you access travels with you, it’s universal.

- Ellis Park is in UK cinemas now

- More film reviews on theartsdesk

Add comment