Schubert gave us a winter’s journey for the 19th century: a wandering lover brooding, remembering, fantasising, maybe even dying to the chilly accompanying churn of the hurdy-gurdy man. In Everest, composer Joby Talbot and librettist Gene Scheer recreate it for the 21st.

A journey of the mind becomes as much one of the body. Love remains, along with memories and fantasies, but now the human beloved must share their place with something else: the mountain. Obsessive, deceptive, all-consuming desire takes vivid form in this powerful operatic debut.

Premiered in Dallas in 2015, Everest – inspired by the horrifying events of 10 May, 1996, in which eight people died on the mountain when a storm hit – only now makes it to the UK. Again it falls to the Barbican to step up where opera companies won’t. As with Dead Man Walking (brought to the UK for the first time by the Barbican in 2018), the piece should have been a no-brainer for ENO and their outstanding salaried chorus and orchestra. For a one-off performance it’s an expensive undertaking, musicians packed right to the edges of the hall’s large stage: a big sound for a big mountain.

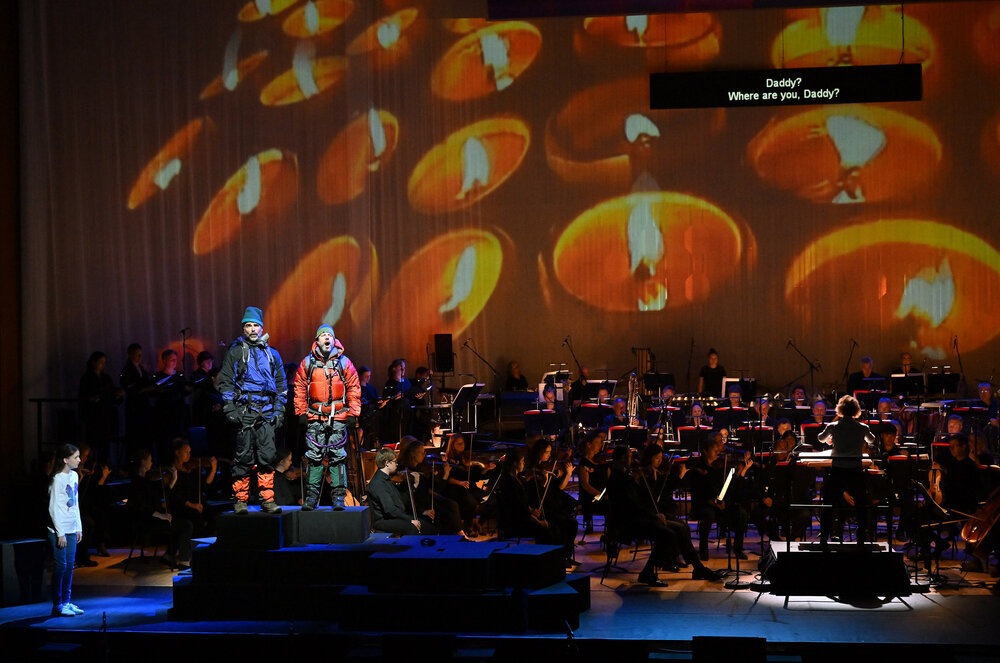

Director Leonard Foglia’s original Dallas staging is revived here in simplified essence by Kristen Barrett. The stage’s three walls become a wrap-around screen, at first grainy with the fizz and haze of static, a digital echo of the wind that will later blast through the action. Projections – maps, mountain-tops, flowers, candles – help place action that unfolds in collage rather than strict chronology, and a couple of black boxes supply the costumed cast with something tangible to climb. But it’s the score that does the heavy-lifting.

Director Leonard Foglia’s original Dallas staging is revived here in simplified essence by Kristen Barrett. The stage’s three walls become a wrap-around screen, at first grainy with the fizz and haze of static, a digital echo of the wind that will later blast through the action. Projections – maps, mountain-tops, flowers, candles – help place action that unfolds in collage rather than strict chronology, and a couple of black boxes supply the costumed cast with something tangible to climb. But it’s the score that does the heavy-lifting.

Talbot’s rhythmic style, the propulsive energy that has made him contemporary ballet’s composer of choice, is a natural fit for a story measured out in units: steps, breaths, days, seconds. The composer sets up a pulse – grinding, twitching, gradually accelerating – that takes the audience’s along with it pace and tension build unremittingly towards the climax. There’s no shortage of surface colour either. We open with the cracking of ice, shuddering through a percussion-heavy ensemble. A pedal note high in the violins supplies a distant horizon-line and cello glissandi nod to Britten’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream, conjuring a landscape no less eerie or alien than his magical forest.

Conductor Nicole Paiement holds everything taut, pacing her own journey with care. With the BBC Singers split across the two sides of the stage, the action is surrounded and driven forwards by chorus writing that extends well beyond commentary, supplying whispering atmospherics, throwing out questions, lamenting, filling the gaps where the mountain’s own voice would be. A concerto for choir by any other name, it was a showcase of exactly what we’d lose if this ensemble (who else could have pulled this performance together so swiftly?) is dismantled by the BBC?

Conductor Nicole Paiement holds everything taut, pacing her own journey with care. With the BBC Singers split across the two sides of the stage, the action is surrounded and driven forwards by chorus writing that extends well beyond commentary, supplying whispering atmospherics, throwing out questions, lamenting, filling the gaps where the mountain’s own voice would be. A concerto for choir by any other name, it was a showcase of exactly what we’d lose if this ensemble (who else could have pulled this performance together so swiftly?) is dismantled by the BBC?

Soloists are no less strong. Both Daniel Okulitch (client-mountaineer Beck Weathers, pictured above) and Andrew Bidlack (expedition leader Rob Hall, pictured below with Craig Verm as Doug Hansen) are veterans of previous stagings, and their relationship with these characters and Talbot’s demanding vocal writing shows. Bidlack in particular makes an almost too beautiful a job of the relentlessly high extremity of his lines, particularly in his heart-breaking final communications over the radio with his colleague Guy (Jimmy Holliday) and his pregnant wife Jan (a radiant Sian Griffiths). Okulitch’s warmth of tone, his ability to shift between folksy, musical-theatre directness and more obviously operatic delivery, make something singular of this unlikely hero.

Scheer (best known in the UK from his work with Jake Heggie) is a canny dramatist, but with an American style of writing that’s often a little rich, too self-consciously, look-at-me poetic for a European palate. Unlike Heggie, Talbot tempers it, refusing to linger or indulge, condensing what could easily be a full-length evening into just 75 minutes. When the names of all those who have died on Everest are projected onto the screens they speak for themselves; the music refuses to hand-wring or emote.

Scheer (best known in the UK from his work with Jake Heggie) is a canny dramatist, but with an American style of writing that’s often a little rich, too self-consciously, look-at-me poetic for a European palate. Unlike Heggie, Talbot tempers it, refusing to linger or indulge, condensing what could easily be a full-length evening into just 75 minutes. When the names of all those who have died on Everest are projected onto the screens they speak for themselves; the music refuses to hand-wring or emote.

It’s a happy creative marriage, a balance of lyrical and percussive, sweet and salty that gives this debut plenty of tang. Talbot and Scheer’s follow-up The Diving Bell and the Butterfly premieres in Dallas later this year. Let’s hope we don’t have to wait another eight years to see it.

Add comment