Romances on British Poetry / The Poet's Echo, English Touring Opera online review - Britten and Shostakovich in a double mirror | reviews, news & interviews

Romances on British Poetry / The Poet's Echo, English Touring Opera online review - Britten and Shostakovich in a double mirror

Romances on British Poetry / The Poet's Echo, English Touring Opera online review - Britten and Shostakovich in a double mirror

Two composers add up to one compelling drama, as ETO cuts its cloth to suit the times

A darkened stage; a pool of light; a solitary figure. And then, flooding the whole thing with meaning, music – even it’s just a soft chord on a piano. It’s no secret to any opera goer that even the barest outlines of a staging can magnify the dramatic potential of a piece of music to a point when it can seem like a completely new work.

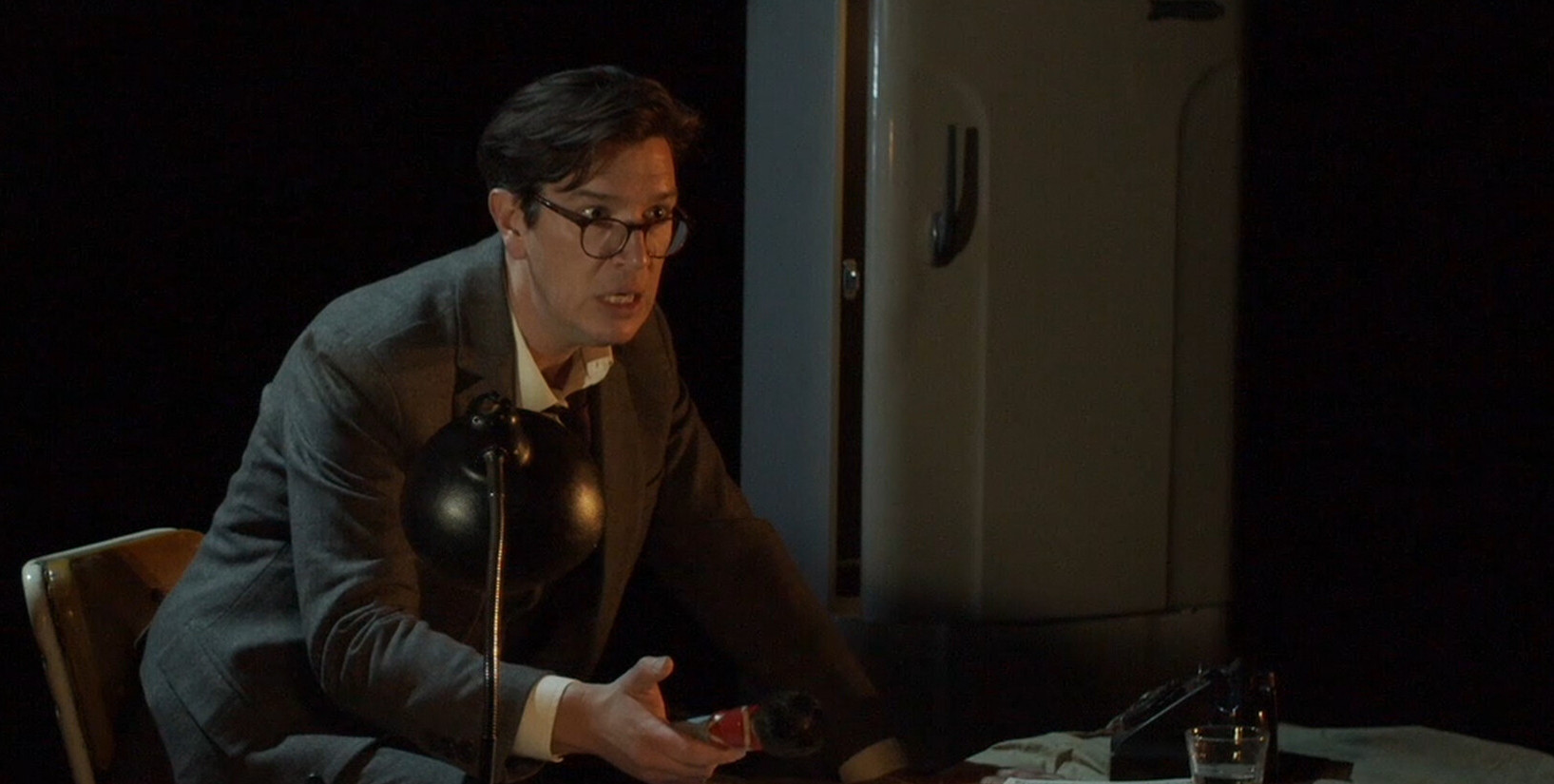

Fairly obvious, of course, why it’s being done now. This concentrated dramatisation of Shostakovich’s Romances on British Poetry and Britten’s Pushkin cycle The Poet’s Echo is just one of four such mini-dramas, conceived for socially distanced touring last autumn under the title Lyric Solitude and now released on film. In their own right, these two cycles add up to a compelling whole: Shostakovich uses English words as a channel for pitch-black Russian irony, while Britten attempts to set Russian verse and (in the process) reveals a rare emotional candour, as well as a profound understanding of his great Russian friend and colleague. The two cycles reflect and heighten one another, even as they tease at the boundaries between their two creators: a process symbolised by the tarnished mirror at the centre of Louie Whitemore’s pared-back stage design.  But this is no shadow play. When the Shostakovich cycle opened with Edward Hawkins (pictured above) sitting at his desk in those unmistakable chunky spectacles as a portrait of Stalin glowered behind him, the heart initially sank. Has any composer been more disastrously served by the tendency to treat every note as coded autobiography? Hawkins picked up and contemplated a toy soldier; later, he crammed volumes of verse into a travelling case. By then, happily, these touches had ceased to be much more than fleeting illustrations: visual footnotes clarifying the real action which was unfolding through Hawkins’ glinting, bitumen bass and his increasingly disturbing range of facial expressions, as bland bewilderment curdled into demonic snarls. A fridge opened to reveal a sawblade; Hawkins danced a wooden jig to words by Burns – delivered, as is almost always the case with ETO, with exemplary clarity.

But this is no shadow play. When the Shostakovich cycle opened with Edward Hawkins (pictured above) sitting at his desk in those unmistakable chunky spectacles as a portrait of Stalin glowered behind him, the heart initially sank. Has any composer been more disastrously served by the tendency to treat every note as coded autobiography? Hawkins picked up and contemplated a toy soldier; later, he crammed volumes of verse into a travelling case. By then, happily, these touches had ceased to be much more than fleeting illustrations: visual footnotes clarifying the real action which was unfolding through Hawkins’ glinting, bitumen bass and his increasingly disturbing range of facial expressions, as bland bewilderment curdled into demonic snarls. A fridge opened to reveal a sawblade; Hawkins danced a wooden jig to words by Burns – delivered, as is almost always the case with ETO, with exemplary clarity.

Throughout it all, Sergey Rybin at the piano played with wry understatement: a presence beyond this nightmare world, represented visually by the soprano Jenny Stafford, who hovered just out of sight in the surrounding gloom. As Hawkins disappeared into the twilight, she stepped in front of the mirror to perform Britten’s songs with luminous warmth riven by flashes of cold, fierce strangeness: never more so than in the birdlike cries of The Nightingale and the Rose. The direction was less overt here, even as the music grew more demonstrative; a masterly balancing act by Conway, and a concentrated performance by Stafford, whose expressions (both vocal and facial) never left you sure whether the poetic spirit she embodied was malevolent, consoling or even wholly real.

The opportunity to see all this close-up, and repeatedly, is one of the great advantages of viewing a production like this on screen, and the film direction – by Tim van Someren – is atmospherically done, with an unerring eye for the illuminating detail as well as a sure sense of when the picture needs to open out and let the drama breathe. It’s currently available on Marquee TV, but with its short length and visual flair it would surely merit a much wider release. If only we had a publicly funded national TV station that was committed to the performing arts, eh? Imagine that.

- Available to stream via English Touring Opera or Marquee TV

- Read more opera reviews on theartsdesk

rating

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Opera

First Person: Kerem Hasan on the transformative experience of conducting Jake Heggie's 'Dead Man Walking'

English National Opera's production of a 21st century milestone has been a tough journey

First Person: Kerem Hasan on the transformative experience of conducting Jake Heggie's 'Dead Man Walking'

English National Opera's production of a 21st century milestone has been a tough journey

Madama Butterfly, Irish National Opera review - visual and vocal wings, earthbound soul

Celine Byrne sings gorgeously but doesn’t round out a great operatic character study

Madama Butterfly, Irish National Opera review - visual and vocal wings, earthbound soul

Celine Byrne sings gorgeously but doesn’t round out a great operatic character study

theartsdesk at Wexford Festival Opera 2025 - two strong productions, mostly fine casting, and a star is born

Four operas and an outstanding lunchtime recital in two days

theartsdesk at Wexford Festival Opera 2025 - two strong productions, mostly fine casting, and a star is born

Four operas and an outstanding lunchtime recital in two days

The Railway Children, Glyndebourne review - right train, wrong station

Talent-loaded Mark-Anthony Turnage opera excursion heads down a mistaken track

The Railway Children, Glyndebourne review - right train, wrong station

Talent-loaded Mark-Anthony Turnage opera excursion heads down a mistaken track

La bohème, Opera North review - still young at 32

Love and separation, ecstasy and heartbreak, in masterfully updated Puccini

La bohème, Opera North review - still young at 32

Love and separation, ecstasy and heartbreak, in masterfully updated Puccini

Albert Herring, English National Opera review - a great comedy with depths fully realised

Britten’s delight was never made for the Coliseum, but it works on its first outing there

Albert Herring, English National Opera review - a great comedy with depths fully realised

Britten’s delight was never made for the Coliseum, but it works on its first outing there

Carmen, English National Opera review - not quite dangerous

Hopes for Niamh O’Sullivan only partly fulfilled, though much good singing throughout

Carmen, English National Opera review - not quite dangerous

Hopes for Niamh O’Sullivan only partly fulfilled, though much good singing throughout

Giustino, Linbury Theatre review - a stylish account of a slight opera

Gods, mortals and monsters do battle in Handel's charming drama

Giustino, Linbury Theatre review - a stylish account of a slight opera

Gods, mortals and monsters do battle in Handel's charming drama

Susanna, Opera North review - hybrid staging of a Handel oratorio

Dance and signing complement outstanding singing in a story of virtue rewarded

Susanna, Opera North review - hybrid staging of a Handel oratorio

Dance and signing complement outstanding singing in a story of virtue rewarded

Ariodante, Opéra Garnier, Paris review - a blast of Baroque beauty

A near-perfect night at the opera

Ariodante, Opéra Garnier, Paris review - a blast of Baroque beauty

A near-perfect night at the opera

Cinderella/La Cenerentola, English National Opera review - the truth behind the tinsel

Appealing performances cut through hyperactive stagecraft

Cinderella/La Cenerentola, English National Opera review - the truth behind the tinsel

Appealing performances cut through hyperactive stagecraft

Tosca, Royal Opera review - Ailyn Pérez steps in as the most vivid of divas

Jakub Hrůša’s multicoloured Puccini last night found a soprano to match

Tosca, Royal Opera review - Ailyn Pérez steps in as the most vivid of divas

Jakub Hrůša’s multicoloured Puccini last night found a soprano to match

Add comment