The Iranian playwright Nassim Soleimanpour is many things, some seemingly contradictory: a) a clever, poetic playwright who uses high-tech elements in his work to inventive effect; b) a mischievous presence who likes to appear in his own highly unusual plays; c) a man in pain who is traumatised by his self-imposed exile from Iran.

This blend helps make his latest, ECHO (Every Cold-Hearted Oxygen), a uniquely enriching experience. This production, which is part of LIFT 2024, is like the pieces he has taken to the Edinburgh Fringe: White Rabbit, Red Rabbit in 2014, Nassim in 2017. It is staged unrehearsed, using a solitary actor who has never seen the script before and spends 80 minutes being prompted through it by texts and whisperings in an earpiece: a process now known as a “cold read”. Fifteen different actors, from Fiona Shaw to Self-Esteem, are stepping up for this role.

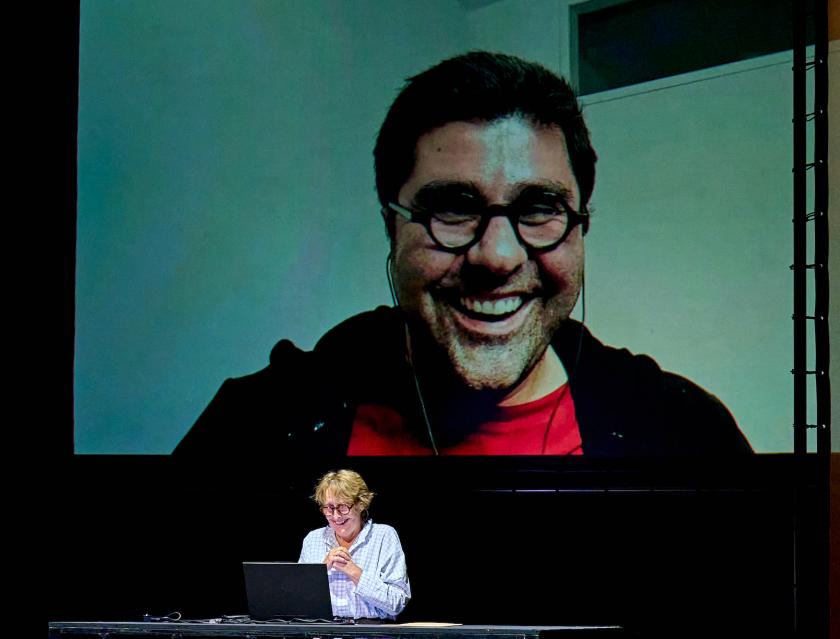

The staging is much more elaborate than this description suggests, even though the set consists of just two large screens for video projections and a laptop on a desk. The key is the inventive use of hi-tech that Soleimanpour and his director, Omar Elerian, deploy. Some is now standard on our stages. When the actor reads the playtext on the laptop screen, for example, its camera feeds his or her image – on press night, Adrian Lester – to a large upright screen. On the big horizontal screen, meanwhile, a head larkily pokes into view from one side: our ringmaster has arrived, Soleimanpour himself. From Berlin, apparently via a live feed. From here things grow surreal and engaging.

The author then seems to guide a camera through his Berlin flat. We pass through the first of many doors to find his wife Shirin cooking dinner and being humorously sarcastic about his lack of contribution to it. As more doors are opened, we begin to realise that anywhere could be on the other side. HIs friend Wolfgang, waiting in Berlin’s Märkischer Hof; a young girl in Wisconsin who gives him a friendship bracelet; his Tehran flat, empty but for a few packing boxes; a bearded Swede, Lars, who appears in an empty landscape on a snowmobile seemingly from nowhere, like a wintry Omar Sharif on his camel. Not all the doors lead to benign places. One opens into the room where the writer was sent to be questioned about White Rabbit, Red Rabbit. Why, the stern official asks him, red, why that colour? When the official notices that the interview is being secretly filmed, he starts quizzing Lester instead, who pretends to be Nassim, offering suitably evasive answers. "Life is not a play," he is admonished by the official.

More doors take us with Nassim through an abandoned building, where, in a faraway room, a television is playing a recording of a man we guess is his novelist father, reading from a book (his own?). The most wrenching encounter is with Nassim's mother, who we realise, as the camera tracks back from a closeup, is surrounded by a film crew as she says goodbye to him, heartbroken that he may never come back. This is an ostentatiously staged performance but with the beating heart and tears of a real person at its core.

There is no hint of voyeurism in the audience’s presence at all these key stations in Nassim’s life. We are a vital part of his process, the script explains, the pilots who can help him navigate his experiences through time and space and join all the dots. He is necessarily a time traveller because his body has to stay put in Iran while he goes wandering. Our gathering together in a theatre, he says in a memorable section, is the force countering the universe’s attempts to explode: “an act of resistance on a galactic scale”.

There is no hint of voyeurism in the audience’s presence at all these key stations in Nassim’s life. We are a vital part of his process, the script explains, the pilots who can help him navigate his experiences through time and space and join all the dots. He is necessarily a time traveller because his body has to stay put in Iran while he goes wandering. Our gathering together in a theatre, he says in a memorable section, is the force countering the universe’s attempts to explode: “an act of resistance on a galactic scale”.

By the final stretch we are moving through dense belts of the cosmos, looking at stars and nebulae (pictured above right, with Kate Maravan), through which autumn leaves suddenly blow from another planet. “We have built a bridge,” Soleimanpour’s script announces to Lester, “to a better future.” By which he means also a better future for his homeland.

The joy of this production is that it never feels pretentious or ponderous. Soleimanpour may see his current work as the belated scream he didn't produce in 2022, when protests started in Tehran and he didn't join in, but he is also a warm, jolly man, despite his obvious sorrow. (Typical of his teasing is that Echo is also the name of his little white fluffy dog.) Accordingly, the production knows when to intrigue and when to serve up an icy dose of reality; when to expound an idea, and when to make us laugh. There is well chosen music as a kind of soundtrack, from traditional Iranian to baroque opera, but the main fibre of the piece is its clever script, which gives the unrehearsed actors just enough to do without making them feel supernumerary. Lester proved an ideal choice, delivering the text with his usual sweet solemnity, but flashing big grins and adding his own dry humour to the mix.

Eventually things build to what feels like a reveal. Will Nassim turn out to be in Sloane Square, not in his Berlin flat? Will he appear onstage? There's a wonderful piece of hi-tech trickery in this finale, but no spoilers allowed. You leave with the same odd combination of elation and melancholy that has distinguished the piece, feeling you too have been on a significant journey.

Add comment