It may seem strange to watch a play about four English people on a kibbutz in the Seventies, and find yourself thinking about Brexit, but that’s precisely what springs to mind here. Culturally blinkered and politically ignorant, most of the characters seem to see their first trip to Israel as little more than an opportunity for sex and better weather.

The Finborough Theatre has a fantastic record in digging out overlooked theatrical gems – not least last month’s On McQuillan’s Hill which played to packed houses. Not Quite Jerusalem was a huge hit for playwright and actor Paul Kember when it opened at the Royal Court 40 years ago, breaking box office records and eventually being made into a (less well received) film. But in the complex, conflicted light of 2020 it just doesn’t sing convincingly any more.

True, the comedy is very much at the expense of the Brits who have misunderstood the utopian kibbutz social experiment. "Bit like a fucking prison camp," moans Dave in the opening scene. "Only I could get on a plane, travel 2,000 miles in search of the sun, step off the plane – and get pissed on." When he and Pete notice that there are dead flies on the sandwiches, Pete jokes "They’re not dead, mate. They’re kosher. They just hang themselves upside down."

The problem is that what might have seemed bracingly irreverent in the early Eighties now now seems no more funny than a bulldog with herpes. The difference between a classic and something that’s simply dated is like the difference between boeuf bourguignon and a packet of prawn cocktail crisps. One improves with age precisely because of its range and complexity. The other might have felt more fun at the time, but because of the broadened outlook of those sampling it, now it just seems flat, stale and synthetic.

It’s a shame, because this is – characteristically of the Finborough – a good and well-acted production. Peter Kavanagh directs a cast that certainly captures the spirit of an era that in its uninhibited sexism and blinkered approach to other cultures feels in itself like a foreign country.

It’s a shame, because this is – characteristically of the Finborough – a good and well-acted production. Peter Kavanagh directs a cast that certainly captures the spirit of an era that in its uninhibited sexism and blinkered approach to other cultures feels in itself like a foreign country.

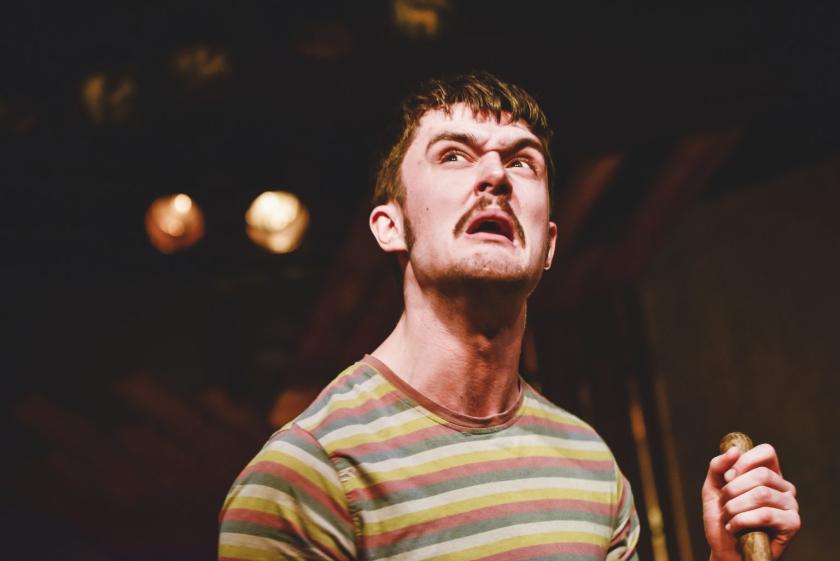

Joe McArdle is a convincingly hapless Dave, while Ronnie Yorke has such a striking comedic stage presence as wide-boy Pete that you wish he had better lines to wrestle with. The central storyline deals with the relationship that develops between Cambridge drop-out, Mike, and one of the female Israeli soldiers on the kibbutz, Gila. This is nicely handled, with a nuanced sympathetic performance from Ryan Whittle as a man sickened by the emptiness of Britain’s institutions and its class system. As his lover, Ailsa Joy (pictured above with Whittle) is amusingly contemptuous to start off with, introducing real depth as the chemistry flares between them.

Yet here again the script fails them. We learn plenty about Mike’s crisis by the end. Yet for all her strength and character, we have very little sense of what Gila’s life is like when she’s not interacting with him. Equally we become aware as the play progresses that Miranda Braun’s Carrie has mental health issues. But she’s basically written off first as an irritation, and then as someone who’s a bit of a curiosity because of the lies she’s told about her personal life.

I did hear a member of the audience praising "the refreshing lack of political correctness", but challenging political correctness is only interesting if it manages to highlight its contradictions and hypocrisies. Here it’s simply symptomatic of a set of people who are struggling to grow up. For all Mike’s attempts to articulate how his fellow Britons might develop if they are truly allowed to live according the democratic principles of the kibbutz, it’s difficult to see how these characters will be able to shift their perspective very far outside their navels. It’s a shame, because the theme of the disposessed white working class struggling to connect to another culture is, for obvious reasons, extremely interesting, but the way it's realised here feels no more edifying than that packet of stale prawn cocktail crisps.

- Not Quite Jerusalem at the Finborough Theatre till 28 March

- Read more reviews on theartsdesk

- @Hallibee1

Add comment