Ulysses, Abbey Theatre / The Tin Soldier, Gate Theatre, Dublin review - peerless Joyce marathon, Andersen squashed | reviews, news & interviews

Ulysses, Abbey Theatre / The Tin Soldier, Gate Theatre, Dublin review - peerless Joyce marathon, Andersen squashed

Ulysses, Abbey Theatre / The Tin Soldier, Gate Theatre, Dublin review - peerless Joyce marathon, Andersen squashed

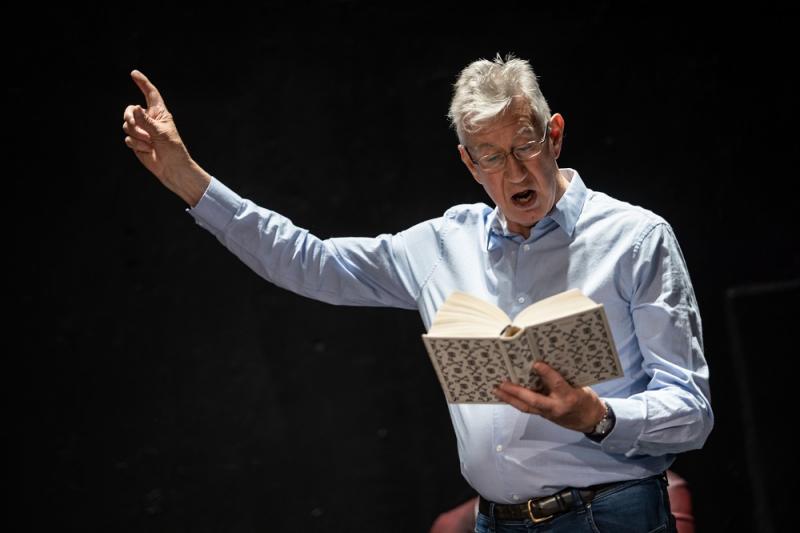

Barry McGovern is odyssey master, while fine performers sag under awful script

A pot plant on a stand, two tables with glasses of water, two chairs – one plush, one high – are all the props needed on the stage of the Abbey’s second theatre, the Peacock, for the ultimate complete reading of James Joyce’s Ulysses in its 100th year. For Barry McGovern is a master: one of Beckett’s favourite actors, on a par with Billie Whitelaw, and immersed in all things Joycean over the past 30 years (★★★★★).

McGovern began his odyssey last Friday morning at 10am, bringing to vivid life the first two, plain-sailing episodes of Ulysses, where we meet Stephen Dedalus not quite happy with Falstaffian mentor Buck Mulligan in the Martello Tower at Dublin’s Sandycove, and still less so with the anti-Semitic Mr Deasey at the school where he’s teaching. Then into Stephen’s head, not easily read as he roves the shore of Dublin bay but hypnotically welcome in McGovern's vocalisation, drawing us towards the darker recesses of a rather lost soul.

There were happy souls able to make all 14 three-or-so-hour sessions; for me, work called on most afternoons. So I had to remember what I’d read of acquaintance with Leopold Bloom, the kindly Jewish bourgeois Dubliner who becomes Stephen’s true spiritual guide; nearly a week later, on Bloomsday morning, 16 June, after the first reading of the day at the Martello Tower – amateur and widely distributed (pictured below) - and a dip in “the Forty Foot” like Mulligan, I’d be eating something like what he had for breakfast – “the inner organs of beasts and fowls” – at Kennedys Bar opposite Swenys Pharmacy where Bloom bought lemon soap and orange blossom water.

The supreme tour de force, of the seven episodes I was able to catch, came in the bewildering dreamscapes of “Circe”, split across Tuesday afternoon and Wednesday morning. The brothels of Nighttown (the Monto red-light area in north-east Dublin, the biggest at the time in the whole of Europe) become real for a time – Joyce knew them from teenage experience – but merge with the obscenities of the unconscious: supremely so when whoremistress Bella Cohen becomes the male “Bello” in dominating a she-pig Bloom. You don’t get filthier than this, and McGovern delivered with full shameless panache. But there were other, less menacing, comic peaks in some of the sequences: when Bloom, humiliated in court, becomes the whipping-post of indignant society ladies, or, flipping to triumph, the regal founder of the new Bloomusalem. And then the strange beauty of the pastoral idyll, a kind of Joycean classical Walpurgis Night à la Goethe, rounded off by the pathos of Bloom’s dead son reappearing as gentle spirit.  That was my last time in the transfixing company of McGovern: while Molly Bloom wove her fantasies in the concluding “Penelope” and the final orgasm had the audience rising to its feet, I was steeped in Sibelius in a two-hour Zoom class. But then there was Bloomsday, and the local celebrations of Dublin’s greatest celebrant.

That was my last time in the transfixing company of McGovern: while Molly Bloom wove her fantasies in the concluding “Penelope” and the final orgasm had the audience rising to its feet, I was steeped in Sibelius in a two-hour Zoom class. But then there was Bloomsday, and the local celebrations of Dublin’s greatest celebrant.

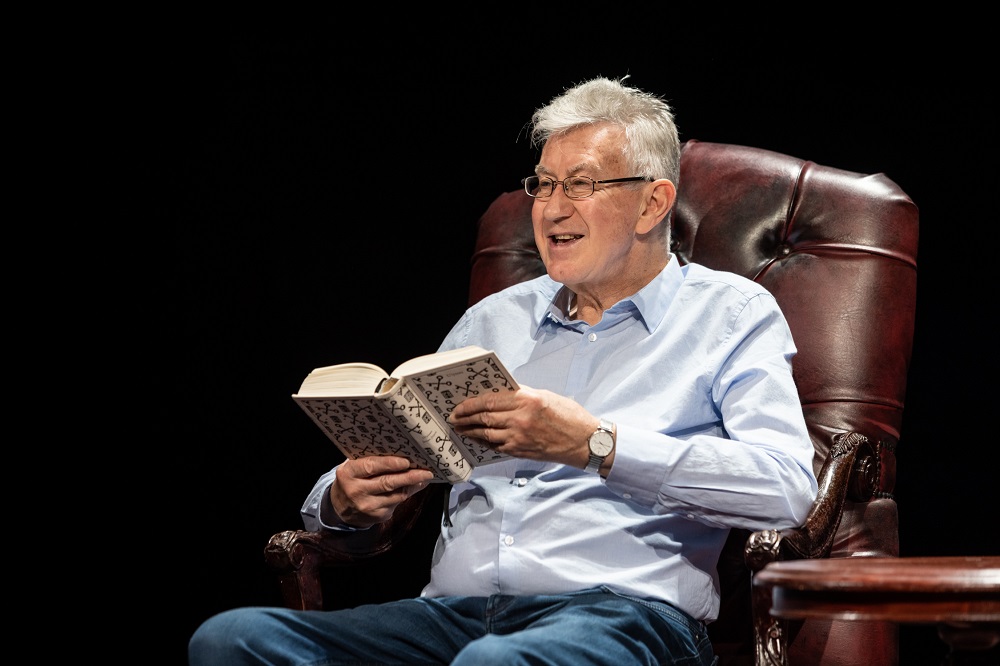

A less happy intermezzo came in a visit to the lovely Gate Theatre and The Tin Soldier, a kind of Hans Christian Andersen cabaret devised by the Gate and Theatre Lovett (★★). Drawing monotonously on the correspondences between Andersen’s fixations on his ugliness and outcast status and the protagonists of his fairy tales, the script by Louis Lovett and Nico Brown proved everything that Andersen’s writings are not: over-sentimental, self-pitying, banal..  No doubt about it, the performers had talent. Lovett as actor (pictured above by Roz Colqohoun on the right with Conor Linehan) could run the gamut of Andersen’s divided selves, ventriloquizing dancer Kevn Coqualard as The Tin Solder’s Devil in the Box with impressive falsetto – repulsive, but intentionally so. Music director Linehan could play the piano beautifully, but the material was mostly of sub-Lloyd-Webber banality. The presence of boy singer Arthur Peregrine and vocalist Olesya Zdorovetska seemed puzzling. So much, lighting and production wise, was thrown at this venture, but to no avail. When you have a single actor of supreme character and the best material in the world, you need none of them.

No doubt about it, the performers had talent. Lovett as actor (pictured above by Roz Colqohoun on the right with Conor Linehan) could run the gamut of Andersen’s divided selves, ventriloquizing dancer Kevn Coqualard as The Tin Solder’s Devil in the Box with impressive falsetto – repulsive, but intentionally so. Music director Linehan could play the piano beautifully, but the material was mostly of sub-Lloyd-Webber banality. The presence of boy singer Arthur Peregrine and vocalist Olesya Zdorovetska seemed puzzling. So much, lighting and production wise, was thrown at this venture, but to no avail. When you have a single actor of supreme character and the best material in the world, you need none of them.

- The Tin Soldier at the Gate Theatre until 2 July; the Abbey Theatre's new production of Brian Friel's Translations has just opened and runs until 13 August

- More theatre reviews on theartsdesk

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £33,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Theatre

A Midsummer Night's Dream, Bridge Theatre review - Nick Hytner's hit gender-bender returns refreshed

This Dream is a great night out, especially for Shakespeare first-timers

A Midsummer Night's Dream, Bridge Theatre review - Nick Hytner's hit gender-bender returns refreshed

This Dream is a great night out, especially for Shakespeare first-timers

Miss Myrtle’s Garden, Bush Theatre review - flowering talent, but needs weeding

New play about loss, love, grief and gardening is humane, but flawed

Miss Myrtle’s Garden, Bush Theatre review - flowering talent, but needs weeding

New play about loss, love, grief and gardening is humane, but flawed

Fiddler on the Roof, Barbican review - lean, muscular delivery ensures that every emotion rings true

This transfer from Regent's Park Open Air Theatre sustains its magic

Fiddler on the Roof, Barbican review - lean, muscular delivery ensures that every emotion rings true

This transfer from Regent's Park Open Air Theatre sustains its magic

In Praise of Love, Orange Tree Theatre review - subdued production of Rattigan's study of loving concealment

Unspoken emotion flows through this late work

In Praise of Love, Orange Tree Theatre review - subdued production of Rattigan's study of loving concealment

Unspoken emotion flows through this late work

Letters from Max, Hampstead Theatre review - inventively staged tale of two friends fighting loss with poetry

Sarah Ruhl turns her bond with a student into a lesson in how to love

Letters from Max, Hampstead Theatre review - inventively staged tale of two friends fighting loss with poetry

Sarah Ruhl turns her bond with a student into a lesson in how to love

Elephant, Menier Chocolate Factory review - subtle, humorous exploration of racial identity and music

Story of self-discovery through playing the piano resounds in Anoushka Lucas's solo show

Elephant, Menier Chocolate Factory review - subtle, humorous exploration of racial identity and music

Story of self-discovery through playing the piano resounds in Anoushka Lucas's solo show

This is My Family, Southwark Playhouse - London debut of 2013 Sheffield hit is feeling its age

Relatable or stereotyped - that's for you to decide

This is My Family, Southwark Playhouse - London debut of 2013 Sheffield hit is feeling its age

Relatable or stereotyped - that's for you to decide

The Frogs, Southwark Playhouse review - great songs save updated Aristophanes comedy

Tone never settles, but Sondheim's genius carries the day

The Frogs, Southwark Playhouse review - great songs save updated Aristophanes comedy

Tone never settles, but Sondheim's genius carries the day

Mrs Warren's Profession, Garrick Theatre review - mother-daughter showdown keeps it in the family

Shaw's once-shocking play pairs Imelda Staunton with her real-life daughter

Mrs Warren's Profession, Garrick Theatre review - mother-daughter showdown keeps it in the family

Shaw's once-shocking play pairs Imelda Staunton with her real-life daughter

The Crucible, Shakespeare's Globe review - stirring account of paranoia and prejudice

Ince's fidelity to the language allows every nuance to be exposed

The Crucible, Shakespeare's Globe review - stirring account of paranoia and prejudice

Ince's fidelity to the language allows every nuance to be exposed

The Fifth Step, Soho Place review - wickedly funny two-hander about defeating alcoholism

David Ireland pits a sober AA sponsor against a livewire drinker, with engaging results

The Fifth Step, Soho Place review - wickedly funny two-hander about defeating alcoholism

David Ireland pits a sober AA sponsor against a livewire drinker, with engaging results

The Deep Blue Sea, Theatre Royal Haymarket review - Tamsin Greig honours Terence Rattigan

The 1952 classic lives to see another day in notably name-heavy revival

The Deep Blue Sea, Theatre Royal Haymarket review - Tamsin Greig honours Terence Rattigan

The 1952 classic lives to see another day in notably name-heavy revival

Add comment