Queen Elizabeth and the Spy in the Palace, Channel 4 review - how the Fourth Man burrowed deep into the British Establishment | reviews, news & interviews

Queen Elizabeth and the Spy in the Palace, Channel 4 review - how the Fourth Man burrowed deep into the British Establishment

Queen Elizabeth and the Spy in the Palace, Channel 4 review - how the Fourth Man burrowed deep into the British Establishment

Did Anthony Blunt uncover secrets which threatened the survival of the house of Windsor?

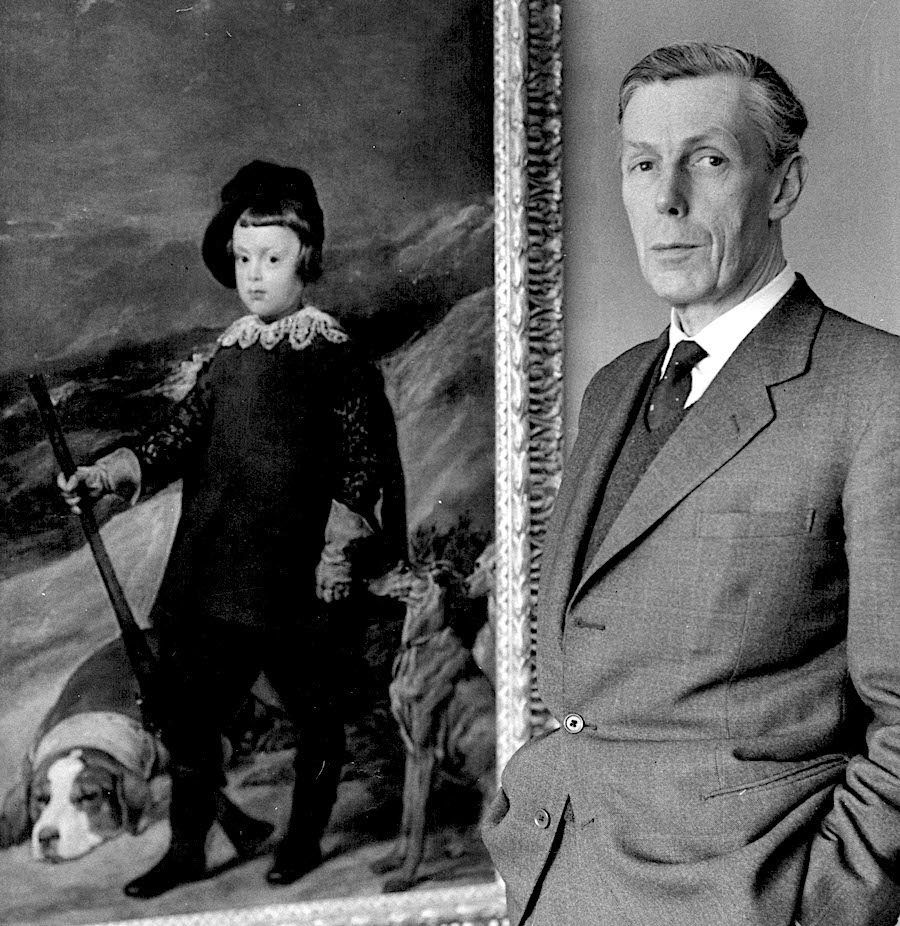

Director of the Courtauld Institute, Surveyor of the Queen’s Pictures and a particular expert on the art of Poussin, Sir Anthony Blunt spent decades at the epicentre of the royal family and the British Establishment.

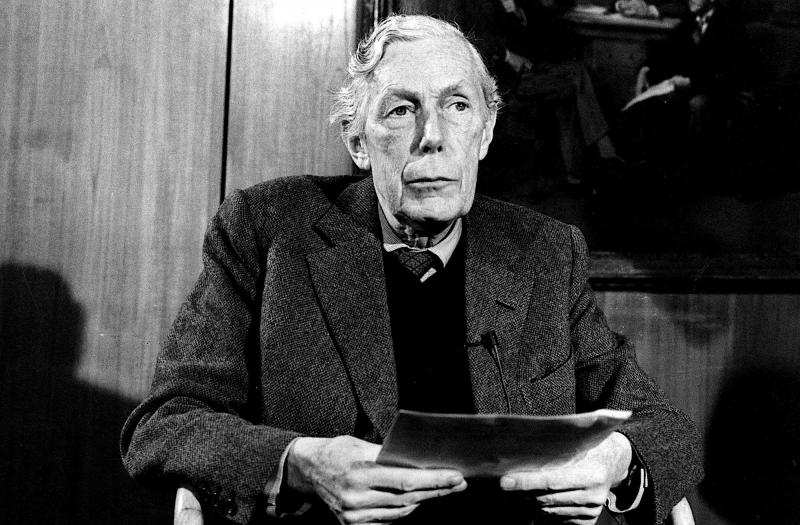

The Blunt story, in all its murky fascination, has long gripped writers, historians, documentary-makers and The Crown’s creator Peter Morgan. Andy Webb's documentary for Channel 4 probably didn’t reveal anything that Blunt-obsessives haven’t already ferreted out elsewhere, but it told the story with punch and panache, aided by some evocative archive footage and historic still photos (Blunt and Cambridge friends, pictured below by Lytton Strachey).

The theme that emerged most strongly was the way Blunt was so closely entwined with royalty and the ruling classes that exposing him might have resulted in catastrophic collateral damage. This would answer the question why, when he’d long been suspected by MI5 of treachery and being in the pay of the Russians, he was left undisturbed for so many years. He came under intense scrutiny after his lover and mentor Guy Burgess defected to Moscow in 1951, and was apparently interviewed 11 times by MI5 between 1951 and 1964, when he finally saw the game was up and confessed to MI5. Even so, this wouldn’t have happened without a tip-off from the FBI. He was given immunity from prosecution in return for the confession, and apparently believed his treason would not be publicly revealed.

The theme that emerged most strongly was the way Blunt was so closely entwined with royalty and the ruling classes that exposing him might have resulted in catastrophic collateral damage. This would answer the question why, when he’d long been suspected by MI5 of treachery and being in the pay of the Russians, he was left undisturbed for so many years. He came under intense scrutiny after his lover and mentor Guy Burgess defected to Moscow in 1951, and was apparently interviewed 11 times by MI5 between 1951 and 1964, when he finally saw the game was up and confessed to MI5. Even so, this wouldn’t have happened without a tip-off from the FBI. He was given immunity from prosecution in return for the confession, and apparently believed his treason would not be publicly revealed.

It wasn’t until Margaret Thatcher was Prime Minister in 1979 that Blunt’s dirty secrets were revealed in the House of Commons. Thatcher, disgusted by what she saw as upper-class cronyism and the Establishment closing ranks to protect itself, described Blunt as “repugnant and contemptible”. It was only then that Blunt was stripped of his knighthood, though his only further punishment was a deluge of hostile publicity. Perhaps they thought hanging was too good for him. As the historian Piers Brendon put it here, “Blunt absolutely got away with it.”

The theory advanced here was that Blunt, who was sent on clandestine missions to Germany in 1945 to rescue assorted letters and artefacts on behalf of the Royal Family, had unearthed evidence of the Windsors’ sympathy for, and possible collusion with, the Nazis, reaching far beyond the well-documented antics of Third Reich fanboy the Duke of Windsor. Blunt dutifully copied the letters to Moscow, and the film quoted Soviet spy Gennady Sokolov’s suggestion that “if the documents discovered by Blunt were published” it would cause a scandal “which could even be the fall of the dynasty” (Blunt in 1962, pictured below by Aubrey Hart).

It’s a fascinating thesis, though incontrovertible proof was lacking. However, as an instructive parable of class and snobbery, the Blunt story takes some beating. He was, to a certain extent, to the manor born, since the Queen Mother (or Mrs George VI) was his third cousin, while his mother Hilda used to be given clothes by Queen Mary. Mixing with a group of posh aesthetes and intellectuals when he went up to Trinity College, Cambridge, he was insulated in this dreamy walled garden from the then-draconian legal penalties for homosexuality, and became infatuated with the extrovert Burgess. It seems the titans of the intelligence community couldn’t comprehend that someone of such rarefied breeding might be capable of such heinous treachery. Compare and contrast with the barbarous treatment meted out to code-cracking genius Alan Turing, a crucial contributor to the Allied victory driven to suicide after his conviction for “gross indecency”.

It’s a fascinating thesis, though incontrovertible proof was lacking. However, as an instructive parable of class and snobbery, the Blunt story takes some beating. He was, to a certain extent, to the manor born, since the Queen Mother (or Mrs George VI) was his third cousin, while his mother Hilda used to be given clothes by Queen Mary. Mixing with a group of posh aesthetes and intellectuals when he went up to Trinity College, Cambridge, he was insulated in this dreamy walled garden from the then-draconian legal penalties for homosexuality, and became infatuated with the extrovert Burgess. It seems the titans of the intelligence community couldn’t comprehend that someone of such rarefied breeding might be capable of such heinous treachery. Compare and contrast with the barbarous treatment meted out to code-cracking genius Alan Turing, a crucial contributor to the Allied victory driven to suicide after his conviction for “gross indecency”.

Blunt’s defence was that he and his contemporaries were drawn into working for the Soviets because Stalin seemed to be the only bulwark against Hitler and fascism, though he never expressed any remorse at having enabled the monstrosities of Stalinism, or for anything else. His trite little homily about it being “a case of political conscience against loyalty to country – I chose conscience” was about as convincing as a fake Poussin scrawled with a Sharpie pen. At least Channel 4 managed to resist the temptation to call this film A Very British Traitor.

rating

Explore topics

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more TV

Blu-ray: The Sweeney - Series One

Influential and entertaining 1970s police drama, handsomely restored

Blu-ray: The Sweeney - Series One

Influential and entertaining 1970s police drama, handsomely restored

I Fought the Law, ITVX review - how an 800-year-old law was challenged and changed

Sheridan Smith's raw performance dominates ITV's new docudrama about injustice

I Fought the Law, ITVX review - how an 800-year-old law was challenged and changed

Sheridan Smith's raw performance dominates ITV's new docudrama about injustice

The Paper, Sky Max review - a spinoff of the US Office worth waiting 20 years for

Perfectly judged recycling of the original's key elements, with a star turn at its heart

The Paper, Sky Max review - a spinoff of the US Office worth waiting 20 years for

Perfectly judged recycling of the original's key elements, with a star turn at its heart

The Guest, BBC One review - be careful what you wish for

A terrific Eve Myles stars in addictive Welsh mystery

The Guest, BBC One review - be careful what you wish for

A terrific Eve Myles stars in addictive Welsh mystery

theartsdesk Q&A: Suranne Jones on 'Hostage', power pants and politics

The star and producer talks about taking on the role of Prime Minister, wearing high heels and living in the public eye

theartsdesk Q&A: Suranne Jones on 'Hostage', power pants and politics

The star and producer talks about taking on the role of Prime Minister, wearing high heels and living in the public eye

King & Conqueror, BBC One review - not many kicks in 1066

Turgid medieval drama leaves viewers in the dark

King & Conqueror, BBC One review - not many kicks in 1066

Turgid medieval drama leaves viewers in the dark

Hostage, Netflix review - entente not-too-cordiale

Suranne Jones and Julie Delpy cross swords in confused political drama

Hostage, Netflix review - entente not-too-cordiale

Suranne Jones and Julie Delpy cross swords in confused political drama

In Flight, Channel 4 review - drugs, thugs and Bulgarian gangsters

Katherine Kelly's flight attendant is battling a sea of troubles

In Flight, Channel 4 review - drugs, thugs and Bulgarian gangsters

Katherine Kelly's flight attendant is battling a sea of troubles

Alien: Earth, Disney+ review - was this interstellar journey really necessary?

Noah Hawley's lavish sci-fi series brings Ridley Scott's monster back home

Alien: Earth, Disney+ review - was this interstellar journey really necessary?

Noah Hawley's lavish sci-fi series brings Ridley Scott's monster back home

The Count of Monte Cristo, U&Drama review - silly telly for the silly season

Umpteenth incarnation of the Alexandre Dumas novel is no better than it should be

The Count of Monte Cristo, U&Drama review - silly telly for the silly season

Umpteenth incarnation of the Alexandre Dumas novel is no better than it should be

The Narrow Road to the Deep North, BBC One review - love, death and hell on the Burma railway

Richard Flanagan's prize-winning novel becomes a gruelling TV series

The Narrow Road to the Deep North, BBC One review - love, death and hell on the Burma railway

Richard Flanagan's prize-winning novel becomes a gruelling TV series

The Waterfront, Netflix review - fish, drugs and rock'n'roll

Kevin Williamson's Carolinas crime saga makes addictive viewing

The Waterfront, Netflix review - fish, drugs and rock'n'roll

Kevin Williamson's Carolinas crime saga makes addictive viewing

Add comment