If you were a fan of “Rock Island Line” when it became a pop hit, you’d have to be at least in your mid-70s now. In 1956, Paul McCartney heard Lonnie Donegan perform it live in Liverpool, and Paul’s rising 77. How many below that age know it is moot, though that doesn’t necessarily disqualify it from the hour-long documentary treatment. For blues lovers, it’s a benchmark. “Rock Island Line” dates from the late 1920s and was first recorded in 1934.

Billy Bragg dependably and articulately fronted up this BBC Four history of the song, a protest paean to, or (as it might once have been called) a Negro spiritual about, a railroad network begun in the mid-19th century. Trains eventually steamed to many points west, south and north of Chicago – Rock Island sits west of Chicago, on the east bank of the Mississippi.

Those first recorded voices of the song belonged to black prisoners in Arkansas, way to the south. Key here was that another erstwhile convict, Huddie William Ledbetter – aka Lead Belly, who was violent but musically hugely influential on the 1950s and 1960s: Dylan references him on his first album – was present at the recording, clocked the performance and made the song his own. He died in 1949.

Those first recorded voices of the song belonged to black prisoners in Arkansas, way to the south. Key here was that another erstwhile convict, Huddie William Ledbetter – aka Lead Belly, who was violent but musically hugely influential on the 1950s and 1960s: Dylan references him on his first album – was present at the recording, clocked the performance and made the song his own. He died in 1949.

About 15 minutes in, after a roll call of those who felt the heat of the song – The Beatles not least of all – the tale started to resemble the Pyramids, or Indiana Jones. Responsible for said Arkansas prison recording was one John Lomax, a musicologist who in his hat and academic glasses evoked George Lucas’s whip-cracking archaeologist. A heavily bearded folk music researcher showed Bragg an extraordinary box containing the mechanism by which Lomax cut his recordings. It might have been something that Darwin took with him on the Beagle.

With Lead Belly having refined the song, enter Ken Colyer. He was a London-based New Orleans-obsessed trumpeter, who in the early 1950s by rather byzantine means, including jumping ship in Mobile, Alabama ended up playing with his jazz heroes on the Big Easy’s Bourbon Street. He was deported, then back in the UK linked up with Chris Barber. Barber is still alive and spoke to camera. His trad-jazz band, among others, helped foment in 1950s white teenagers a keen, and decidedly post-rationing, interest in African-American music.

That’s a potted version of an amazingly tangled sequence of transatlantic connections, which Bragg adeptly held together, though by halfway through a diagram or family tree wouldn’t have gone amiss. The film’s nub was skiffle – a word, according to Bragg, that was “obscure”, came from “African-American roots culture” and was a way of getting around the culturally-appropriating awkwardness of white musicians claiming they “play the blues”.

Lonnie Donegan was part of Barber’s troupe and had a solo smash in 1955 with a rivetingly energetic version of “Rock Island Line”, heard here in its entirety. Donegan emerged from skiffle. That was all about musical DIY: washboard for percussion, broom handle with string and empty tea-chest for bass, acoustic guitars. Bragg’s marvelling at skiffle’s ingenuity belied the fact that its paraphernalia resembles, today, degraded antiquities discovered in an old cupboard.

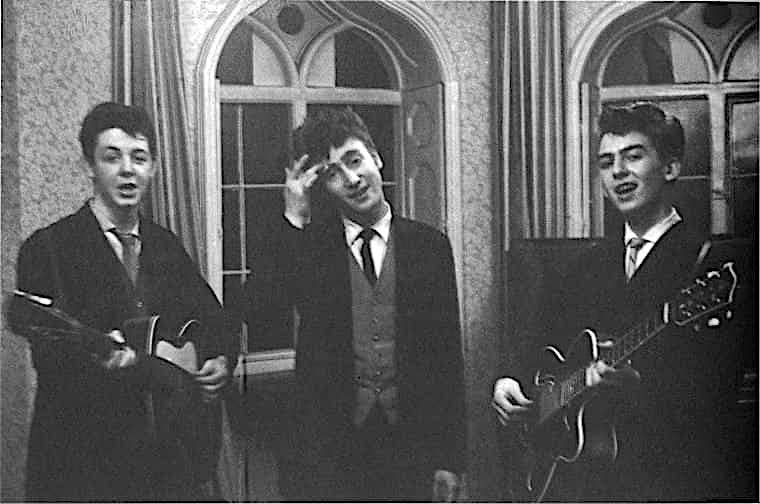

Sales of guitars when Donegan and his ilk hit the UK airwaves leapt from 5,000 to 250,000 a year. John Lennon formed the skiffle group The Quarrymen in late 1956 (pictured above, in 1958). Six months later, having chanced upon Paul, he was being told by his Little Richard-loving junior that to get ahead their band had to write their own stuff.

Paul should have been in this film. Instead, towards the end, a trio of amiable men who knew both John and Paul, recalled – in the Woolton church hall where the two met – how fast skiffle came and went. Bragg said it lasted 18 months. Donegan didn’t have much of a career afterwards, though a short contemporaneous interview clip with him underlined how vividly he felt the form was about fighting racial prejudice. It was a theme that got an airing in the film but remained unprobed.

As the credits rolled, we could probably have done without Bragg’s somewhat tuneless rendition of “Rock Island Line”. But by this point, even if throughout the film there had been a surfeit of detail, the Barking troubadour had made a solid case for the song’s pre-Beatles importance. Yet the question remains: why in the 21st century, research purposes aside, would anyone want to listen to it?

Add comment