Chinese artist, Ai Weiwei has created an extremely beautiful installation at the Design Museum in which the disparate elements play their part in creating a powerful overall message. On one level the exhibition is about design, but it also invites you to consider far more serious issues than are normally addressed in this temple to consumerism.

A deep sense of loss permeates the exhibition. In fact, the longer I stayed the more I was reminded of the terrible photographs taken at Auschwitz that record the mounds of hair and piles of shoes collected from those killed in the camp’s gas chambers.

Ai Weiwei spent 12 years in the United States before returning to Beijing in 1993 and was amazed by the changes that had taken place in his absence. A determination to modernise as quickly as possible meant there was little interest in or respect for the past. China’s cultural heritage was being dismantled and its historical artefacts destroyed, sold abroad or simply thrown away. So he began haunting flea markets, buying discarded items for next to nothing and, in the process, amassing a large collection of relics, many of which have been used to make these installations.

Laid out on the floor are carpets of ancient artefacts which query the way we use and value things; an item may be deemed worthless by one group of people, for instance, yet be considered priceless by another. Still Life 1993-2000 (pictured above) consists of 4,000 stone age tools – from axe heads, chisels and knives to spinning wheels. Arranged in rows, they act as a testament to the ingenuity of our ancestors. In a display case nearby is an exquisite jade knife resembling a tongue and a Neolithic hand axe from which the shape of an iPhone has been cut. One tool was used for millennia but is now considered useless, the other is regarded as essential until, that is, a new model supersedes it.

Still Life 1993-2000 (pictured above) consists of 4,000 stone age tools – from axe heads, chisels and knives to spinning wheels. Arranged in rows, they act as a testament to the ingenuity of our ancestors. In a display case nearby is an exquisite jade knife resembling a tongue and a Neolithic hand axe from which the shape of an iPhone has been cut. One tool was used for millennia but is now considered useless, the other is regarded as essential until, that is, a new model supersedes it.

The clash of ancient and modern value systems is succinctly addressed by an earthenware urn from the Han Dynasty (206 BCE-220 CE) onto which the artist has stencilled the Coca Cola logo (pictured below right). A precious artefact from an important moment in China’s cultural history is emblazoned with a symbol representing globalisation and the erasure of cultural difference.

Shocked by the speed at which the existing urban fabric was being torn down to make way for new buildings, in 2002 Ai Weiwei began photographing the spaces left by the demolition. They show a city shattered and scarred, its history erased and its people displaced. Hanging outside an apparently derelict shack, overlooking a demolition site, is a line of washing; against all odds the occupant is still hanging on. The skyline is dotted with the high rise blocks that have since transformed Beijing from a Chinese city into a modern metropolis just like any other.

Ancient temples and court yard houses were also being torn down, so the artist was able to buy these historically important buildings and incorporate them in his work. In Through 2007-8 he anchors the wooden beams of a Qing Dynasty temple (1644-1911 CE) with tables from the same period to create an installation that resembles a building hit by an earthquake – a symbol, if you like, of a culture wilfully destroyed from within.

Ancient temples and court yard houses were also being torn down, so the artist was able to buy these historically important buildings and incorporate them in his work. In Through 2007-8 he anchors the wooden beams of a Qing Dynasty temple (1644-1911 CE) with tables from the same period to create an installation that resembles a building hit by an earthquake – a symbol, if you like, of a culture wilfully destroyed from within.

Untitled (Porcelain Balls) 2022 (main picture) is a carpet of little porcelain spheres, tiny cannon balls made during the Song Dynasty (960-21279 CE). It’s hard to believe these delicate objects were designed to kill people. Of course, the 200,000 on display are a minute fraction of the numbers produced, which invites you to reconsider the relationship between mass production – designed to achieve uniformity – and hand crafting, which we identify with the creation of unique pieces. By churning out identical items, those workers were expected to function like machines.

Craftsmen in the Song Dynasty also produced hand-made porcelain tea pots. If a pot was imperfect, its spout was deliberately broken off. Spouts 2015 is a dense carpet consisting of 250,000 spouts. These elegant rejects remind one that mass production and the mountains of waste it produces are nothing new. People have always been profligate, but now there are billions of us discarding stuff in vast quantities. The demand for uniformity is a potent metaphor for the suppression of individuality in today’s China. The broken spouts serve as reminder that, nowadays, those who refuse to conform are arrested, silenced and ultimately broken.

In 2011 Ai Weiwei was arrested for criticising the state and was kept in solitary confinement for 81 days before being released as a result of international pressure. In 2018 the police raided his Beijing studio, smashing the work and demolishing the building. Left Right Studio Material 2018 is a carpet of broken pieces of blue porcelain salvaged from the studio after the raid. Its jagged edges are a testament to the violence enacted against the artist and his work.

Ai Weiwei now lives abroad, moving restlessly from one country to another, but he still makes work in response to events back in China. Snaking its way across one wall is a giant serpent (main picture) made from the grey and black rucksacks used by Chinese school children. 5,197 of them were killed when their substandard schools collapsed in the Sichuan earthquake of 2008. Bad design, or rather corrupt builders, contributed to their deaths.

Ai Weiwei now lives abroad, moving restlessly from one country to another, but he still makes work in response to events back in China. Snaking its way across one wall is a giant serpent (main picture) made from the grey and black rucksacks used by Chinese school children. 5,197 of them were killed when their substandard schools collapsed in the Sichuan earthquake of 2008. Bad design, or rather corrupt builders, contributed to their deaths.

You may remember the installation he made at the Royal Academy in 2015. Having salvaged 200 tonnes of steel rebars from the schools destroyed in the earthquake, he straightened the lengths of twisted metal and arranged the bars on the floor in an orderly pile alongside the names of the children who died. The simplicity and directness of the piece gave it enormous resonance; people cried. But I doubt if anyone will be as moved by the snake, which is too decorative to have the same impact.

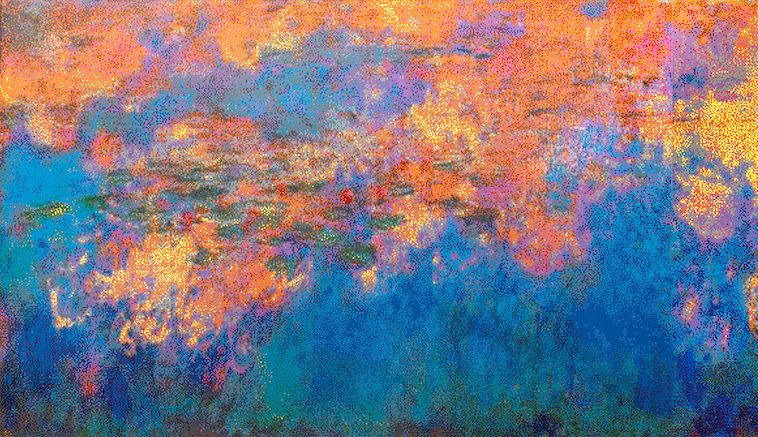

The same is true of a companion snake made from the blue and red life jackets left on the beaches of Lesbos by boat loads of Syrian refugees. Ai has previously wrapped the pillars of Berlin’s concert hall in these abandoned lifejackets and stuffed thousands more into the window recesses of Copenhagen’s Charlottenborg Palace. The raw power of those installations came from their intrusiveness; they were deliberately confrontational. This serpent, on the other hand, is too accommodating to make anyone feel uncomfortable. A whole wall is covered in a version of Monet’s 15m long triptych Waterlilies (1914-26) (pictured above: detail). Made with 650,000 studs of Lego bricks, the image is just about recognisable from a distance but, close up, all you see are individual plastic studs (pictured above left: detail of Lego Incident, 2014 discarded lego pieces). This mechanical replication of brushwork presages the increasing use of robots in advertising and elsewhere. Illustrators and designers are already being replaced by bots programmed to scan and cannibalise existing artworks. In the process, human creativity is rendered obsolete.

A whole wall is covered in a version of Monet’s 15m long triptych Waterlilies (1914-26) (pictured above: detail). Made with 650,000 studs of Lego bricks, the image is just about recognisable from a distance but, close up, all you see are individual plastic studs (pictured above left: detail of Lego Incident, 2014 discarded lego pieces). This mechanical replication of brushwork presages the increasing use of robots in advertising and elsewhere. Illustrators and designers are already being replaced by bots programmed to scan and cannibalise existing artworks. In the process, human creativity is rendered obsolete.

The elegance of Ai Weiwei’s exhibition tends to camouflage the anger and sadness permeating much of the work. But if you linger, they slowly rise to the surface to lend his installations profound resonance and meaning.

- Ai Weiwei: Making Sense at the Design Museum until 30 July

- More visual arts reviews on theartsdesk

Add comment