Angela de la Cruz/ Anna Maria Maiolino, Camden Arts Centre | reviews, news & interviews

Angela de la Cruz/ Anna Maria Maiolino, Camden Arts Centre

Angela de la Cruz/ Anna Maria Maiolino, Camden Arts Centre

Intimations of death and renewal in an evocative survey of two artists

Friday, 02 April 2010

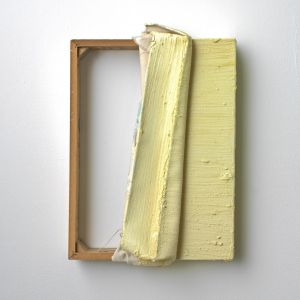

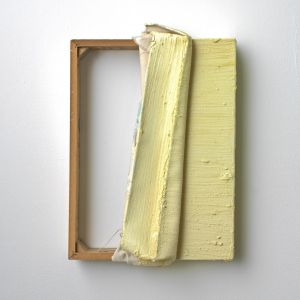

Acts of wanton destruction appear to have taken place at Camden Arts Centre, as canvases lie crushed, ripped, crumpled and broken. Monochrome and minimalist works have had their stretchers, their very backbones, ripped and cracked in two, and their once taut, painted surfaces hang, in some instances, like flayed skin. Their broken carcasses are arranged in a seemingly haphazard fashion, hanging precariously from walls or stuffed into corners. They lie forlornly on the floor, or are pushed with some force into armchairs. The gallery looks like the scene of a crime, as if we have chanced upon acts of malicious sabotage. Just who is responsible for this mayhem?

Angela de la Cruz is an artist who’s been around for a long time. She has perpetrated countless calculated acts of violence against defenceless paintings for the last two decades, but this is her first solo exhibition in a public gallery. “My starting point,” she explains, “was deconstructing painting. One day I took the cross bar out and the painting bent. From that moment on, I looked at the painting as an object.” And these objects are given anthropomorphic names: Homeless, Deflated, Ashamed. No wonder they cower in corners. Taken apart, or “deconstructed” they also appear in a naked state of transformation, from painting to sculptural object, but like a sculpture that’s failed, exhausted by the process of mutation. They've just given up, deflated, ashamed, with nowhere to hide.

And it’s not just canvases. More recently Cruz has taken to destroying furniture. A plastic chair has its spindly legs splayed out on the floor. It looks like an animal whose fragile limbs have been broken in a trap. And there are wardrobes, which look like coffins, hanging on walls. One is balanced unevenly on top of another, ready to topple at the merest puff of air. It looks like a wobbly T, or a truncated cruciform. Religious connatations spring to mind. In fact, thoughts of religion and death waft through the quiet rooms. Is it me, or is it like a morgue in here?

its spindly legs splayed out on the floor. It looks like an animal whose fragile limbs have been broken in a trap. And there are wardrobes, which look like coffins, hanging on walls. One is balanced unevenly on top of another, ready to topple at the merest puff of air. It looks like a wobbly T, or a truncated cruciform. Religious connatations spring to mind. In fact, thoughts of religion and death waft through the quiet rooms. Is it me, or is it like a morgue in here?

The unstable cruciform coffins are in a room where there is a huge canvas stretcher on the floor, placed like a futon, in the middle of the room and covered with a painted white, stiffly rumpled canvas, as if the effects of rigor mortis have taken hold. It looks like a double bed, and of course, it evokes a a sense of absence, as beds which are empty often do. On another wall there is a canvas that has been folded and spread out in the shape of a concertinaed fan. It’s painted a dark orange, but its heat fails to warm up this ghost of a room. The way the mind is running, it could be a neglected fireplace, a cold furnace.

Cruz’s works are deeply evocative, suggestive and quietly unsettling. And they are positioned in ways that suggest narratives of loss, abandonment, even fear, but in a way that is bracing and rather brilliant. You look at these exhausted, inert objects as one might a powerful memento mori painting, with a kind of renewed vigour at simply being alive.

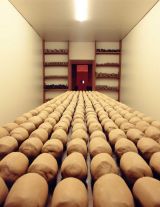

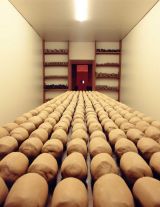

Meanwhile, an act of transformation is taking place in the gallery devoted to the work of Brazilian artist Anna Maria Maiolino. On tiered plywood tables dense lumps and clods of clay have been formed into different shapes and neatly arranged in tightly packed, regimented rows. You might be looking at a conveyor belt in a biscuit factory: round cookies, chocolate fingers, soft-centred truffles, rolled chocolate logs. Elsewhere, there are sacks of haggis, salami, Cumberland sausages, or great hunks of bread dough.

formed into different shapes and neatly arranged in tightly packed, regimented rows. You might be looking at a conveyor belt in a biscuit factory: round cookies, chocolate fingers, soft-centred truffles, rolled chocolate logs. Elsewhere, there are sacks of haggis, salami, Cumberland sausages, or great hunks of bread dough.

Why might we think of food, when these are just things in themselves? But associations bubble up unbidden. And while they possess the sensual, tactile quality of damp cold clay, you know that the pieces will soon to turn into dry clay. They will crack and eventually turn to rubble and dust, though if watered they can also be revived and remoulded. That is the quality of clay, the very substance that we ourselves were made from, if you want to dig deep into certain creation mythologies.

And like Cruz’s broken works, these too tell an evocative story about fragility and the possibility of renewal.

And it’s not just canvases. More recently Cruz has taken to destroying furniture. A plastic chair has

its spindly legs splayed out on the floor. It looks like an animal whose fragile limbs have been broken in a trap. And there are wardrobes, which look like coffins, hanging on walls. One is balanced unevenly on top of another, ready to topple at the merest puff of air. It looks like a wobbly T, or a truncated cruciform. Religious connatations spring to mind. In fact, thoughts of religion and death waft through the quiet rooms. Is it me, or is it like a morgue in here?

its spindly legs splayed out on the floor. It looks like an animal whose fragile limbs have been broken in a trap. And there are wardrobes, which look like coffins, hanging on walls. One is balanced unevenly on top of another, ready to topple at the merest puff of air. It looks like a wobbly T, or a truncated cruciform. Religious connatations spring to mind. In fact, thoughts of religion and death waft through the quiet rooms. Is it me, or is it like a morgue in here?The unstable cruciform coffins are in a room where there is a huge canvas stretcher on the floor, placed like a futon, in the middle of the room and covered with a painted white, stiffly rumpled canvas, as if the effects of rigor mortis have taken hold. It looks like a double bed, and of course, it evokes a a sense of absence, as beds which are empty often do. On another wall there is a canvas that has been folded and spread out in the shape of a concertinaed fan. It’s painted a dark orange, but its heat fails to warm up this ghost of a room. The way the mind is running, it could be a neglected fireplace, a cold furnace.

Cruz’s works are deeply evocative, suggestive and quietly unsettling. And they are positioned in ways that suggest narratives of loss, abandonment, even fear, but in a way that is bracing and rather brilliant. You look at these exhausted, inert objects as one might a powerful memento mori painting, with a kind of renewed vigour at simply being alive.

Meanwhile, an act of transformation is taking place in the gallery devoted to the work of Brazilian artist Anna Maria Maiolino. On tiered plywood tables dense lumps and clods of clay have been

formed into different shapes and neatly arranged in tightly packed, regimented rows. You might be looking at a conveyor belt in a biscuit factory: round cookies, chocolate fingers, soft-centred truffles, rolled chocolate logs. Elsewhere, there are sacks of haggis, salami, Cumberland sausages, or great hunks of bread dough.

formed into different shapes and neatly arranged in tightly packed, regimented rows. You might be looking at a conveyor belt in a biscuit factory: round cookies, chocolate fingers, soft-centred truffles, rolled chocolate logs. Elsewhere, there are sacks of haggis, salami, Cumberland sausages, or great hunks of bread dough.Why might we think of food, when these are just things in themselves? But associations bubble up unbidden. And while they possess the sensual, tactile quality of damp cold clay, you know that the pieces will soon to turn into dry clay. They will crack and eventually turn to rubble and dust, though if watered they can also be revived and remoulded. That is the quality of clay, the very substance that we ourselves were made from, if you want to dig deep into certain creation mythologies.

And like Cruz’s broken works, these too tell an evocative story about fragility and the possibility of renewal.

- Angela de la Cruz / Anna Maria Maiolino are at the Camden Arts Centre until 30 May

more Visual arts

Expressionists: Kandinsky, Münter and the Blue Rider, Tate Modern review - a missed opportunity

Wonderful paintings, but only half the story

Expressionists: Kandinsky, Münter and the Blue Rider, Tate Modern review - a missed opportunity

Wonderful paintings, but only half the story

Eye to Eye: Homage to Ernst Scheidegger, MASI Lugano review - era-defining artist portraits

One of Switzerland's greatest photographers celebrated with a major retrospective

Eye to Eye: Homage to Ernst Scheidegger, MASI Lugano review - era-defining artist portraits

One of Switzerland's greatest photographers celebrated with a major retrospective

Stephen review - a breathtakingly good first feature by a multi-media artist

Melanie Manchot's debut is strikingly intelligent and compelling

Stephen review - a breathtakingly good first feature by a multi-media artist

Melanie Manchot's debut is strikingly intelligent and compelling

Fantastic Machine review - photography's story from one camera to 45 billion

Love it or hate it, the photographic image has ensnared us all

Fantastic Machine review - photography's story from one camera to 45 billion

Love it or hate it, the photographic image has ensnared us all

Yinka Shonibare: Suspended States, Serpentine Gallery review - pure delight

Weighty subject matter treated with the lightest of touch

Yinka Shonibare: Suspended States, Serpentine Gallery review - pure delight

Weighty subject matter treated with the lightest of touch

Jane Harris: Ellipse, Frac Nouvelle-Aquitaine MÉCA, Bordeaux review - ovals to the fore

Persistence and conviction in the works of the late English painter

Jane Harris: Ellipse, Frac Nouvelle-Aquitaine MÉCA, Bordeaux review - ovals to the fore

Persistence and conviction in the works of the late English painter

Sargent and Fashion, Tate Britain review - portraiture as a performance

London’s elite posing dressed up to the nines

Sargent and Fashion, Tate Britain review - portraiture as a performance

London’s elite posing dressed up to the nines

Zineb Sedira: Dreams Have No Titles, Whitechapel Gallery review - a disorientating mix of fact and fiction

An exhibition that begs the question 'What and where is home?'

Zineb Sedira: Dreams Have No Titles, Whitechapel Gallery review - a disorientating mix of fact and fiction

An exhibition that begs the question 'What and where is home?'

Yoko Ono: Music of the Mind, Tate Modern review - a fitting celebration of the early years

Acknowledgement as a major avant garde artist comes at 90

Yoko Ono: Music of the Mind, Tate Modern review - a fitting celebration of the early years

Acknowledgement as a major avant garde artist comes at 90

Unravel: The Power and Politics of Textiles in Art, Barbican review - the fabric of dissent

An ambitious exploration of a neglected medium

Unravel: The Power and Politics of Textiles in Art, Barbican review - the fabric of dissent

An ambitious exploration of a neglected medium

When Forms Come Alive, Hayward Gallery review - how to reduce good art to family fun

Seriously good sculptures presented as little more than playthings or jokes

When Forms Come Alive, Hayward Gallery review - how to reduce good art to family fun

Seriously good sculptures presented as little more than playthings or jokes

Entangled Pasts 1768-now, Royal Academy review - an institution exploring its racist past

After a long, slow journey from invisibility to agency, black people finally get a look in

Entangled Pasts 1768-now, Royal Academy review - an institution exploring its racist past

After a long, slow journey from invisibility to agency, black people finally get a look in

Add comment