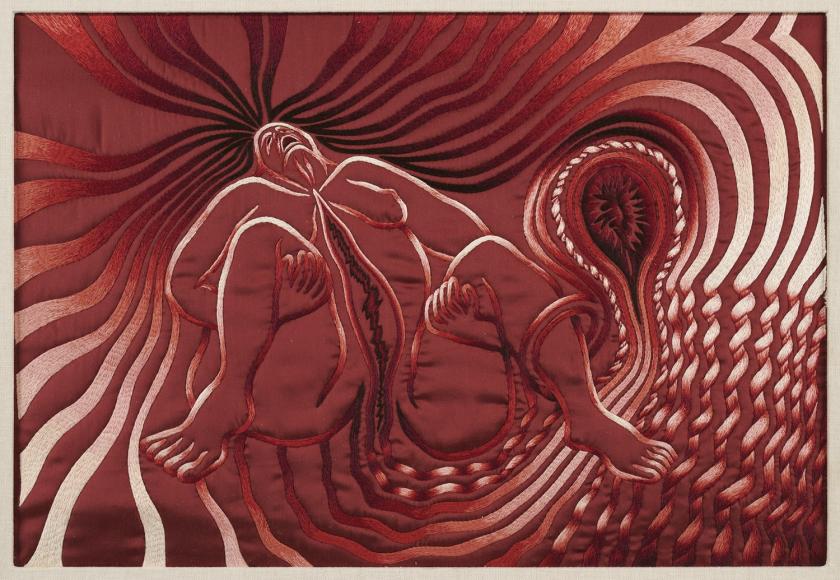

Judy Chicago created Birth Project in the 1980s, recognising with typical perspicacity that the favouring of “the paint strokes of the great male painters” over “the incredible array of needle techniques that women have used for centuries” has implications far beyond the precedence of one art form over another. She saw that a gendered hierarchy of art forms had contributed to the erasure of female experience, and pointed to the “iconographic void” where images of childbirth in western art might be.

Appearing early on in the show, Birth Tear/Tear, 1982, is an extraordinary evocation of the sensations of childbirth, embroidered by Jane Gaddie Thompson as part of Birth Project. Though specifically concerned with female experience, in emphasising image-making as an expression of power or the lack of it, it offers the boldest possible statement of the exhibition’s major themes. For while a great deal of the work on display here is by women, picking up themes from RE/SISTERS, Barbican’s previous show on ecofeminism, as well as Tate’s revelatory Magdalena Abakanowicz survey, its scope is broader, and shows how the marginalisation of “lesser” textile-based art forms correlates to the marginalisation of swathes of people due to gender, race, geography and wealth.

As clothes, and furnishings, and other household goods, textiles have always been traded, or passed from generation to generation, and the exhibition picks up on this inherent quality, setting up broad exchanges between objects and artists across time and place,which are organised into six thematic sections.

As clothes, and furnishings, and other household goods, textiles have always been traded, or passed from generation to generation, and the exhibition picks up on this inherent quality, setting up broad exchanges between objects and artists across time and place,which are organised into six thematic sections.

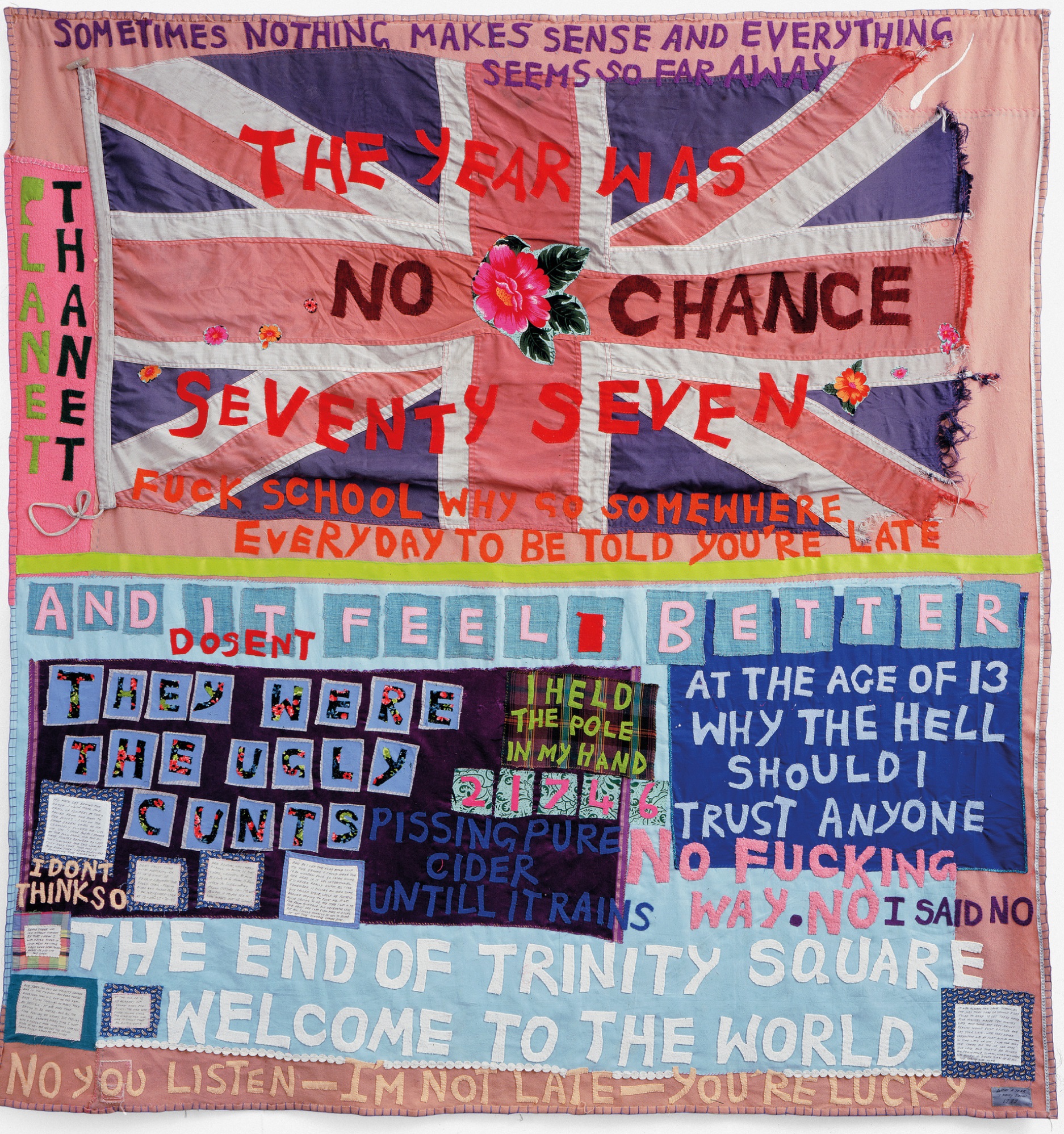

The first, “Subversive Stitch”, looks at the ways in which the domestic associations of textiles have been appropriated or rejected as expressions of resistance and protest. Tracey Emin’s appliqué blanket (Pictured above right) documenting her rape in 1977 is a shockingly effective example of this repurposing, the blanket's associations with comfort, safety, home and family, jarring horribly with the appliquéd words describing her violation. It echoes too, the quilts made by African-American women at Gee’s Bend, Alabama, examples of which appear nearby, made by Loretta Pettway (b. 1942). Still dirtied and stained from use, their designs belong to a tradition that has evolved over two centuries, combining the spontaneity that comes from making do, with design elements that have been passed through generations, and shared between makers.

Egyptian artist Ghada Amer uses embroidery as a literal cover for an act of artistic defiance in her Pink Landscape – RFGA, 2007, in which she has used, vivid, Ab Ex-like threads of colour to obscure, though not hide, a canvas covered with faint, but detailed images of masturbating women. It's a ferociously eloquent piece, born from rage triggered in the 1980s when she was refused entry to a painting class on the grounds of her gender.

As is characteristic of recent Barbican shows, this exhibition is not only thoughtful and responsive to current strands of debate in wider society, but just as importantly, it is gorgeously staged. The atrium-like central space is used to display large scale works by Cecilia Vicuña (Pictured below), Lenore Tawney, Sarah Zapata and others, their monumental forms enjoyed at both gallery levels, the pungent smell of hemp and other fibres adding to the effect. If I have a complaint, it concerns the texts, which though not excessive, are small and difficult to read for those of us in our reading-glasses era, and the ensuing back and forth between object and wall disrupts a varied and exciting hang. A handsheet helps, but as it contains neither titles, nor all the texts, it is not a complete solution. One of the most stunning moments in the show is South African artist Igshaan Adams’s installation opening the section called “Borderlands”. Bejewelled clouds of metal wire evoke the parched expanses of the veld, something of its light and magic captured in the colours and textures of beaded sculptures, that Adams has developed from his weaving practice. The installation explores “desire lines”, the footpaths created through repeated use, and that in post-apartheid South Africa have a special meaning as expressions of free will, and the breaking and crossing of boundaries.

One of the most stunning moments in the show is South African artist Igshaan Adams’s installation opening the section called “Borderlands”. Bejewelled clouds of metal wire evoke the parched expanses of the veld, something of its light and magic captured in the colours and textures of beaded sculptures, that Adams has developed from his weaving practice. The installation explores “desire lines”, the footpaths created through repeated use, and that in post-apartheid South Africa have a special meaning as expressions of free will, and the breaking and crossing of boundaries.

Storytelling, is the common thread in all of the 100 or so works on display here, made by 50 international artists working from the 1960s to today. Bearing witness is implicit, but few do this in the intensely visceral manner of Mexican artist Teresa Margolles, whose patchwork tapestries, laid flat in glass cases, take on the aura of religious relics. One tapestry includes the blood of a woman assassinated in Panama City; another was laid at the site where Eric Garner, a Black man, was murdered by the New York Police. Both examples were embroidered by the relatives and friends of the deceased, and serve not only as records of outrage and protest, but also of mourning and remembrance.

An equivalence between the body and sewn fabric is achieved through the use of human hair in place of thread in Angela Su’s embroidered images of sewn body parts, made in response to the violence that erupted following the 2019 pro-democracy protests in Hong Kong. Harmony Hammond’s Bandaged Grid #9, 2020, is a grisly, apparently blood-soaked abstract design that doubles as a maimed simulacrum.

An equivalence between the body and sewn fabric is achieved through the use of human hair in place of thread in Angela Su’s embroidered images of sewn body parts, made in response to the violence that erupted following the 2019 pro-democracy protests in Hong Kong. Harmony Hammond’s Bandaged Grid #9, 2020, is a grisly, apparently blood-soaked abstract design that doubles as a maimed simulacrum.

The lower gallery is dedicated to the show’s final theme, “Ancestral Threads”, highlighting the histories and traditions embodied by textiles. Yinka Shonibare's Boy on a Globe, 2008, is included for its batik-printed cotton to consider colonisation and global trade, while American artist Kevin Beasley creates “ghost” sculptures from old clothes and fabrics, shaped and set in resin, as if imbued with the people who once wore them.

Not all artists draw on their own cultural heritage, and Lenore Tawney, a foundational figure in the American mid-century fibre arts movement, studied many different textile traditions to arrive at her own unique style. Equally, for Polish artist Magdalena Abakanowicz, whose fleshy, richly smelling forms are both bodies and embracing shelters, the act of weaving sisal or hemp transcends culture, and is concerned instead with the elemental, life-giving properties of the earth (Pictured above left: Magdalena Abakanowicz,Vêtement Noir (Black Garment), 1968).

The creation of textiles as an act of communion and respect for the earth brings the exhibition to a close, and Celia Vicuña’s delicate objects, among the smallest in a show that favours the monumental, take weaving as an effective metaphor for the interconnectedness of all things.

Add comment