Bloomberg New Contemporaries, ICA | reviews, news & interviews

Bloomberg New Contemporaries, ICA

Bloomberg New Contemporaries, ICA

Emerging artists show low-key work that doesn't shout to be heard

As I wandered round this year’s New Contemporaries at the ICA, a few yards away in Trafalgar Square, thousands of students braved the cold for the third time to protest against the Government’s proposed spending cuts on education. How many art students joined the rally is impossible to tell, since most London art schools have been swallowed up by universities and lost their individual identities in the process. Whereas the high-profile sit-ins of 1968 were orchestrated by students from Hornsey College of Art (now part of Middlesex University) and, 20 years later, students from Camberwell College of Art (now part of the University of the Arts, London) were leading vociferous protests against cuts in art school funding, any art students involved in the current unrest are all but invisible.

It says something, I think, about the way they see their role in relation to society. Art has become such big business that artists can no longer think of themselves as outsiders – troublemakers; on the contrary, they are key players in an industry that contributes serious money to the economy both from sales of exclusive commodities and in the form of cultural tourism. While London’s galleries and museums attract millions of visitors each year, the Frieze Art Fair brings in plane-loads of collectors; and as wary investors switch their funds to commodities such as art and gold that retain their value, London’s auction houses are also thriving.

Art students must find the situation rather confusing; on the one hand, they are preparing for entry into one of the few areas of the economy that is still vibrant, while, on the other, they are invited to join protests against government cuts. But the 49 recent graduates and undergraduates showing in New Contemporaries seem unperturbed by such contradictions. The words that come to mind to describe the tenor of the exhibition are modest, thoughtful and considered. They are not glamorous or sexy qualities and these exhibitors don’t set out to please or seduce which, paradoxically, makes their work more engaging and far more pleasurable.

It may seem invidious to pick out one or two from this commendably low-key company, but some people inevitably stand out. Johann Arens (Goldsmiths) steals the show with a video installation (main picture) that deliberately confuses here and there, indoors and out, and reality and aspiration. In two images (one projected on the wall, one screened on a monitor), he juxtaposes the geometry of the urban landscape (damply mouldering concrete, the neat brick walls of a new housing estate) with shots of a furniture showroom and an art installation featuring fake bricks, a revolving pot plant and a levitating Chesterfield. With gentle surrealism, he celebrates our ability to see things as they might be, as well as for what they are.

Elsewhere, a banquet has been arranged in the middle of nowhere (pictured right). Soon the vultures arrive and, in less than 11 minutes, they devour everything bar the garnishing. It's Bünuel meets Beckett in this dystopian scenario elegantly filmed by Greta Alfaro (Royal College) in a static shot with ambient sound.

Elsewhere, a banquet has been arranged in the middle of nowhere (pictured right). Soon the vultures arrive and, in less than 11 minutes, they devour everything bar the garnishing. It's Bünuel meets Beckett in this dystopian scenario elegantly filmed by Greta Alfaro (Royal College) in a static shot with ambient sound.

In the middle of an empty road in America’s Midwest, Sophie Eagle (the Slade) stages the tranquil demise of the utopian dream. Rebuilt from gleaming, lightweight units easily unbalanced by a breath of wind, Brancusi’s Endless Column (that enduring symbol of Modernist aspiration) survives only a few minutes before gracefully toppling to the ground.

Kristian de la Riva’s (Central St Martin’s) beautifully drawn animation (pictured left) similarly pokes gentle fun at heroic gestures. Using various sharp instruments – knives, a hand saw, a chainsaw, an electric fan – a nude performer nonchalantly lops of his toes, fingers, ear, leg and penis only to return to glorious good health in the next frame. Pain without consequence.

Kristian de la Riva’s (Central St Martin’s) beautifully drawn animation (pictured left) similarly pokes gentle fun at heroic gestures. Using various sharp instruments – knives, a hand saw, a chainsaw, an electric fan – a nude performer nonchalantly lops of his toes, fingers, ear, leg and penis only to return to glorious good health in the next frame. Pain without consequence.

While studying in Hangzhou, China, Pablo Wendel (Royal College) staged an extraordinary performance that challenged the conformism expected of citizens in the People’s Republic. Disguised as a terracotta figure, he joined the ranks of the life-sized warriors on display in the excavated tomb of the First Emperor of Qin. Alerted to his presence by a visitor, a guard tries to persuade him to leave; many urgent phone calls later, his colleagues arrive and unceremoniously carry off the intruder – but to what fate? The consequences of this rebellious incursion are not revealed.

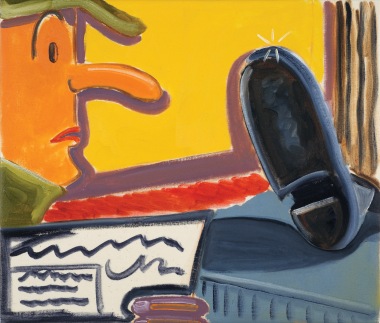

Ian Homerston (Royal College) and Alec Kronacker (the Slade) prove that painting can be potent yet modest. In Homerston’s small canvases, the underpainting bleeds through like a memory to confuse surface and ground. A yellow border invades the grey topcoat with wedge-shaped flickers of sharp colour while, elsewhere, the pink edge intrudes to disrupt a skein of dense black with jagged bands of unexpected brilliance. Meanwhile, Kronacker’s claustrophobic little canvases (pictured above right: Twentieth Century Man) are beautifully orchestrated gems posing as one-liners. Strange encounters between awkward shadows, Fauvist colours and cartoon characters – men with cloth caps, sausage noses and shiny boots – produce an atmosphere of alienation tinged with incipient hysteria. Is that oddly shaped woman really kneeing that painting and, if so, what pent-up fury is being unleashed? Rather than narrative conundrums, though, these are light-hearted essays in deft paint handling; Andy Capp seen through the eyes of Philip Guston and Alex Katz.

Ian Homerston (Royal College) and Alec Kronacker (the Slade) prove that painting can be potent yet modest. In Homerston’s small canvases, the underpainting bleeds through like a memory to confuse surface and ground. A yellow border invades the grey topcoat with wedge-shaped flickers of sharp colour while, elsewhere, the pink edge intrudes to disrupt a skein of dense black with jagged bands of unexpected brilliance. Meanwhile, Kronacker’s claustrophobic little canvases (pictured above right: Twentieth Century Man) are beautifully orchestrated gems posing as one-liners. Strange encounters between awkward shadows, Fauvist colours and cartoon characters – men with cloth caps, sausage noses and shiny boots – produce an atmosphere of alienation tinged with incipient hysteria. Is that oddly shaped woman really kneeing that painting and, if so, what pent-up fury is being unleashed? Rather than narrative conundrums, though, these are light-hearted essays in deft paint handling; Andy Capp seen through the eyes of Philip Guston and Alex Katz.

- Bloomberg New Contemporaries at ICA until 23 January, 2011

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Visual arts

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

Sir Brian Clarke (1953-2025) - a personal tribute

Remembering an artist with a gift for the transcendent

Sir Brian Clarke (1953-2025) - a personal tribute

Remembering an artist with a gift for the transcendent

Emily Kam Kngwarray, Tate Modern review - glimpses of another world

Pictures that are an affirmation of belonging

Emily Kam Kngwarray, Tate Modern review - glimpses of another world

Pictures that are an affirmation of belonging

Kiefer / Van Gogh, Royal Academy review - a pairing of opposites

Small scale intensity meets large scale melodrama

Kiefer / Van Gogh, Royal Academy review - a pairing of opposites

Small scale intensity meets large scale melodrama

Jenny Saville: The Anatomy of Painting, National Portrait Gallery review - a protégé losing her way

A brilliant painter in search of a worthwhile subject

Jenny Saville: The Anatomy of Painting, National Portrait Gallery review - a protégé losing her way

A brilliant painter in search of a worthwhile subject

Abstract Erotic, Courtauld Gallery review - sculpture that is sensuous, funny and subversive

Testing the boundaries of good taste, and winning

Abstract Erotic, Courtauld Gallery review - sculpture that is sensuous, funny and subversive

Testing the boundaries of good taste, and winning

Edward Burra, Tate Britain review - watercolour made mainstream

Social satire with a nasty bite

Edward Burra, Tate Britain review - watercolour made mainstream

Social satire with a nasty bite

Ithell Colquhoun, Tate Britain review - revelations of a weird and wonderful world

Emanations from the unconscious

Ithell Colquhoun, Tate Britain review - revelations of a weird and wonderful world

Emanations from the unconscious

Rachel Jones: Gated Canyons, Dulwich Picture Gallery review - teeth with a real bite

Mouths have never looked so good

Rachel Jones: Gated Canyons, Dulwich Picture Gallery review - teeth with a real bite

Mouths have never looked so good

Yoshitomo Nara, Hayward Gallery review - sickeningly cute kids

How to make millions out of kitsch

Yoshitomo Nara, Hayward Gallery review - sickeningly cute kids

How to make millions out of kitsch

Hamad Butt: Apprehensions, Whitechapel Gallery review - cool, calm and potentially lethal

The YBA who didn’t have time to become a household name

Hamad Butt: Apprehensions, Whitechapel Gallery review - cool, calm and potentially lethal

The YBA who didn’t have time to become a household name

Add comment