Carrie Mae Weems is the first live black artist to have a solo show at New York’s Guggenheim Museum, yet she is hardly known here at all. So the Barbican’s retrospective is timely, especially since, at 70, Weems is making her best work yet.

The climax of the show is The Shape of Things: a Video in 7 Parts 2021(main picture). This vast, multi-screen experience enfolds you in a panoramic take on American society. Sitting enthroned at the centre is performer, Okwui Okpokwasili. Sheets of paper drift around her like snow flakes – documents, perhaps, recording life in America. And her role is to bear witness.

The video starts gloriously with a murmuration of birds weaving complex patterns across the blue sky that fills the enormous curved screen. It’s an image of harmony, of the creative potential of co-operation while, on the soundtrack, we hear about a demographic shift in the U.S.A from white and black people to brown, from polarity to fusion.

Then comes the backlash, a rise in white suprematism. Archive footage shows a throng of black protestors confronting a wall of white segregationists and the violent assault on the Capitol of January 6th. A clown conducts a brass band and an animal trainer puts elephants through their paces; the circus of American politics grinds inexorably on and black people become a target.

Then comes the backlash, a rise in white suprematism. Archive footage shows a throng of black protestors confronting a wall of white segregationists and the violent assault on the Capitol of January 6th. A clown conducts a brass band and an animal trainer puts elephants through their paces; the circus of American politics grinds inexorably on and black people become a target.

Lasting 40 minutes, this extravaganza could feel like an anger-fuelled rant, yet it is mesmerising, partly because the seven parts are so well orchestrated and partly because the visuals are so compelling. Documentary footage is intercut with sections from earlier videos; desperate refugees storm international borders and, seen in black silhouette, slave owning ladies sip afternoon tea. Dressed in black with headdresses resembling skyscrapers, three women move with statuesque solemnity. Like a Greek chorus, they provide an oblique commentary on the unfolding drama. Other scenes are metaphorical. Standing under a studio-induced downpour, several black women smile defiantly, the embodiment of resilience.

Poetic words invite us to see things from a black perspective, to imagine what it’s like to live under constant threat, the police being your worst enemy. “Imagine that you are always stopped, always charged, always convicted. Imagine the worst and know it is always happening.” Imagine a cop demands to see your ID and when you reach into your pocket, he thinks you’re going for a gun. “A shot is fired and boom! you go down.”

We hear the hysterical voice of a white woman calling the police from Central Park. “An African American man is threatening my life,” she yells. Birdwatcher, Christian Cooper has requested that she put her dog on a lead. Her reaction would be laughable, if there wasn’t so much at stake. Wisely, Cooper filmed the encounter; otherwise he faced years rotting in jail.

We hear the hysterical voice of a white woman calling the police from Central Park. “An African American man is threatening my life,” she yells. Birdwatcher, Christian Cooper has requested that she put her dog on a lead. Her reaction would be laughable, if there wasn’t so much at stake. Wisely, Cooper filmed the encounter; otherwise he faced years rotting in jail.

We are invited, in the words of poet Carl Hancock Rux, “to ponder creative solutions”. Dressed in shimmering sequins and a fluffy white crown, a smiling beauty queen perches on a swing as Jimmy Durante croons "Love is the answer". It makes for a wonderfully kitsch climax, but no-one is fooled; the drones are still sent down to work themselves to death in a clip from Fritz Lang’s dystopian film Metropolis.

The Shape of Things is a tour de force, one of those rare experiences that sweeps you up and makes you see things differently. “I’m trying in my humble way to connect the dots, to confront history,” says Weems. And, of course, this ambitious work didn’t spring from nowhere; in fact, for three decades the artist has been making photographs and videos that explore, in various ways, issues around race and gender.

Weems first came to attention with Kitchen Table Series 1990 (pictured above right), as set of 20 black and white photographs in which she appears alone or with a man, her daughter or various female friends. Spotlit from above, the table becomes an arena for the exploration of domestic intimacy and conflict. Each scene is a tableau vivant, meticulously crafted to convey the interplay between characters.

Love is in the air as the couple embrace or share a meal. Increasingly, though, he appears distracted and distant, until finally he leaves the picture altogether. Attention shifts to the dynamics between mother and daughter. The most disarming scene is of them sitting in companionable silence each applying make-up. We see her relaxing with friends, but her loneliness becomes ever more palpable.

Love is in the air as the couple embrace or share a meal. Increasingly, though, he appears distracted and distant, until finally he leaves the picture altogether. Attention shifts to the dynamics between mother and daughter. The most disarming scene is of them sitting in companionable silence each applying make-up. We see her relaxing with friends, but her loneliness becomes ever more palpable.

The series is both ordinary and epic, mundane and profound. It is also revolutionary since the white people who normally occupy centre stage have been replaced by black actors who are usually relegated to marginal roles or cast as criminals and misfits. “For the most part”, says Weems, “our lives remain invisible. Blackness is an affront to the persistence of whiteness.”

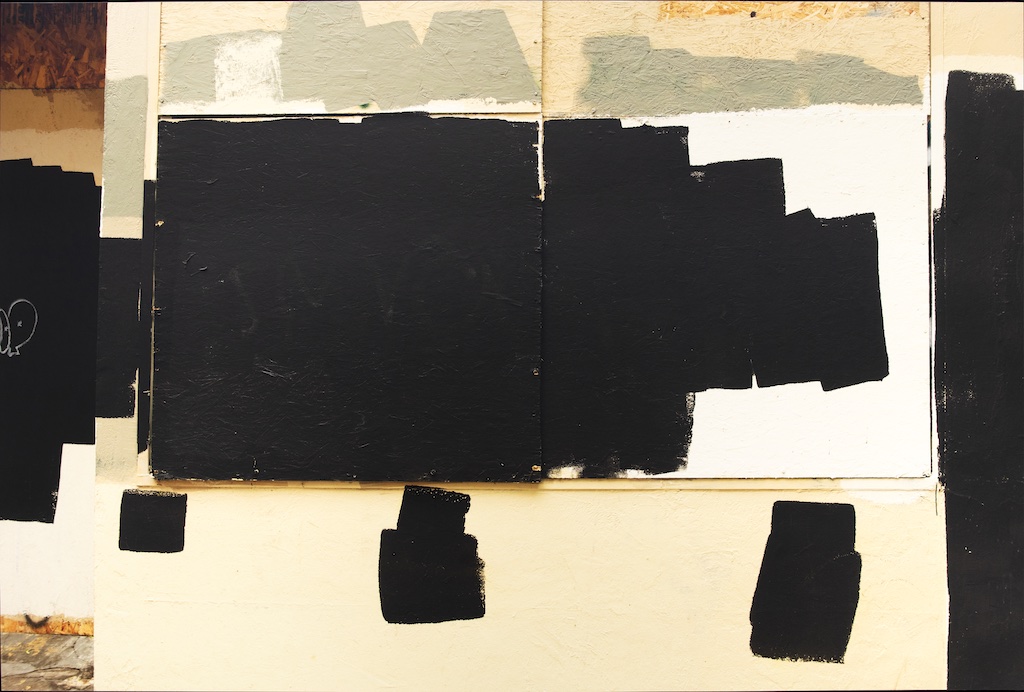

That was in the 1990s and Painting the Town, 2021, (pictured above) demonstrates how black people are still being excluded and silenced. Following the calculated murder of George Floyd by a police officer, demonstrators in Portland, Oregon gave vent to their fury by spraying slogans onto the boarded-up shop fronts. The authorities repeatedly painted over the offending graffiti with slabs of white, grey and black paint and, ironically, the results of their censorship bear an uncanny resemblance to abstract expressionist paintings. So Weems’s photographs of the impromptu paintings draw comparisons between the muzzling of the protestors and the exclusion of black painters from art history.

Those threats remain all too real. It’s Over: a Diorama 2021 (pictured above) is a memorial to the many black people killed by police in recent years. Heavy red curtains enclose a tableau that features photos of the dead surrounded by candles, flowers, a crucifix, balloons, teddy bears and a stuffed swan. Inspired by the shrines built by grieving families to commemorate their loved ones, it is gloriously kitsch and extremely moving. The rage and the sorrow are still raw; this is real life as well as art.

- Carrie Mae Weems is at the Barbican until 3rd September

- More visual arts reviews on theartsdesk

![SEX MONEY RACE RELIGION [2016] by Gilbert and George. Installation shot of Gilbert & George 21ST CENTURY PICTURES Hayward Gallery](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_125_x_125_/public/mastimages/Gilbert%20%26%20George_%2021ST%20CENTURY%20PICTURES.%20SEX%20MONEY%20RACE%20RELIGION%20%5B2016%5D.%20Photo_%20Mark%20Blower.%20Courtesy%20of%20the%20Gilbert%20%26%20George%20and%20the%20Hayward%20Gallery._0.jpg?itok=3oW-Y84i)

Add comment