My relationship with the artist Brian Clarke, the subject of my forthcoming film, goes back a long way: when I first filmed him for a documentary I made for BBC Two in 1993 - a film about windows as symbols and metaphors in the series The Architecture of the Imagination - I was not only struck by the outstanding quality of his work as a painter and stained-glass artist, but by the exceptionally articulate and perceptive way in which he talked about art.

There was an eloquence there – as well as charm and a great deal of biting humour – and an unusual intellectual freshness and depth. He was, above all, immensely inspiring and there was something in the way he communicated about his path through the creative process that was infectious. You couldn’t leave him without a renewed faith in the power of the imagination. All of this added up to a must-make film, a project which I kept thinking about over the ensuing years and which has now finally made it to the screen.

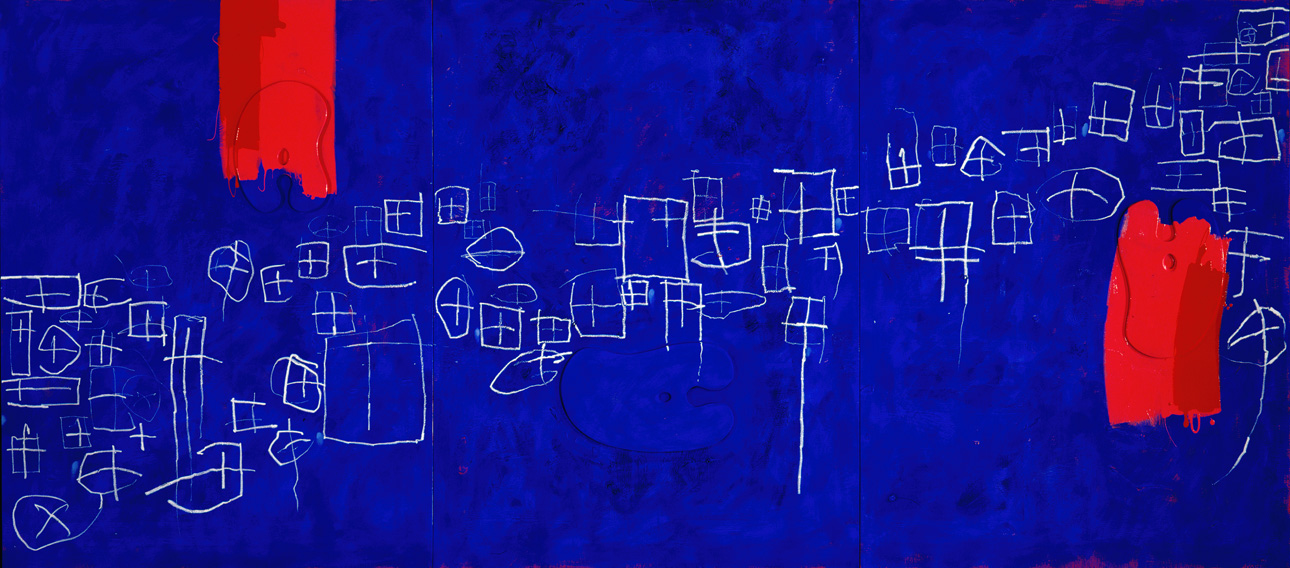

Clarke is one of Britain’s hidden treasures: he not only paints – mostly large semi-abstract canvases – but designs spectacular stained glass, which has been commissioned by clients from Japan to Kazakhstan, from Sweden to Brazil and from Switzerland to the United States. The range of his work is breathtaking – though he is not generally recognised for it or even credited. When it came to choosing a secondary title for the documentary, he suggested “An Artist Apart”, as Clarke feels that he exists in what he describes in the film as a “parallel world”. To the V&A he is a fine artist but, because of his association with stained glass, the Tate thinks of him as a mere craftsman. (Pictured below, Elegy to Lost Time, 1994, private collection.)

Stained glass has fusty associations, but Clarke has transformed the medium, continually exploring its possibilities, from making vast panels of glass without any lead to creating works where there is only lead and no glass at all, playing with the two extremes, as art historian Martin Harrison points out, of “absolute transparency and absolute opacity”.

There is something instantly pleasing about Clarke’s work with glass and he has chosen to work in public spaces – shopping malls as well as churches, mosques and synagogues, airports – as well as private homes and corporate headquarters. He believes passionately that light, shining through large sheets of coloured glass, has the power to change people’s lives. It is perhaps this commitment to touching people directly and changing the architectural and urban spaces they move through that has alienated a critical consensus which would have art provoke conceptual questions, rather than create accessible moments of transcendence.

Clarke has also been tarred with the reputation of one who hangs out with stars, not least those from the world of rock'n'roll

But Clarke has also, from the time of his first breakthrough on the London scene in the late 1970s, fired by punk energy and an unstoppable sense of his own destiny, been tarred with the reputation of one who hangs out with stars – not least those from the world of rock’n’roll. This tendency – fuelled at the time by his dealer Robert Fraser’s connections with a new wave of rich musician collectors (many of them art school graduates) – is of course perfectly kosher in the sensation-seeking celeb-driven world of today’s contemporary art, not to say de rigueur. But in the late Seventies it suggested not being a serious artist, and the mud that was slung at him stuck.

Clarke is a man of contrasts and paradoxes: he is articulate, extrovert and often very provocative. His rather un-English arrogance can offend but, as his ex-wife the artist Liz Finch suggests, he may act this way to hide the fact that he has remained the shy and basically introverted person he was when they first met at art school in their teens.

He is also steeped in tradition: he is immensely knowledgeable about architecture from the Renaissance to the 20th century, as well as about art, literature and music. He may be close friends with Paul McCartney and Jools Holland, but he is also a discerning connoisseur of classical music. He has also been transformed by contemporary culture: there is no doubt that the experience of punk rock touched something deep inside him, a fierce and ironic urge to stand up to and undermine the establishment. And yet he lives in a magnificent Arts and Crafts house in Kensington – where Basquiat and Bacon co-exist with Burne-Jones – and regularly goes on research trips to find inspiration from the arts of centuries past. (Pictured left, Clarke's glass in the Stamford Cone, Connecticut, courtesy of Skidmore, Owings and Merrill.)

He is also steeped in tradition: he is immensely knowledgeable about architecture from the Renaissance to the 20th century, as well as about art, literature and music. He may be close friends with Paul McCartney and Jools Holland, but he is also a discerning connoisseur of classical music. He has also been transformed by contemporary culture: there is no doubt that the experience of punk rock touched something deep inside him, a fierce and ironic urge to stand up to and undermine the establishment. And yet he lives in a magnificent Arts and Crafts house in Kensington – where Basquiat and Bacon co-exist with Burne-Jones – and regularly goes on research trips to find inspiration from the arts of centuries past. (Pictured left, Clarke's glass in the Stamford Cone, Connecticut, courtesy of Skidmore, Owings and Merrill.)

How was I to communicate, in an hour, the richness and range of my subject? It was a challenge I have faced before – with subjects as diverse as Tricky, Balthus, Norman Foster, Ravi Shankar, Robert Wyatt, Boy George, Derek Jarman and others. I had very little time as, after trying to raise money for several years and having started to shoot some material of Brian at work in 2007, I was suddenly offered a very small amount of funding by the BBC – on the condition I finish the film in three months. It felt risky, but the opportunity was too good to miss, and with supplementary finance from Dutch and Australian TV channels, some collaborators who were willing to work for less than the going rate, as well as a good deal of help from the staff at Brian’s studio, I embarked on the project.

There is something to be said for severe constraints: they concentrate the mind and stimulate instinct and intuition, basic tools of creative documentary film-making. I had been mulling the film over for years and a good deal of that kind of preparatory work goes on unconsciously. When the moment comes, decisions are made almost automatically – as if the essential ingredients for the film are in some way already in place.

I decided to film Brian on a visit to Lancashire, convinced as I was that his working-class and spiritualist roots in Oldham were crucial to understanding both man and artist. His matriarchal working-class family had a formative influence on him, and the grandmother, mother and aunts who “fussed over him” as he fondly puts it today, gave him the confidence to follow his own instincts – for he had known in his heart, at the age of 10, that he would be an artist.

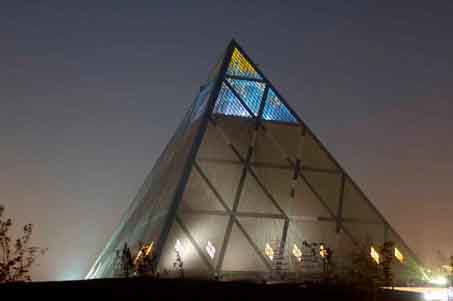

When we discussed what I should shoot for the documentary, Brian left it very much up to me. With limited funds, I could not fly to Brasil, Riyadh, New York or travel to a cathedral way north of Stockholm, let alone get to Kazakhstan - all places which featured important work. (Pictured right, Lord Foster's Pyramid of Peace, Astana, Kazakhstan, with the apex by Brian Clarke © 2006 Brian Clarke)

When we discussed what I should shoot for the documentary, Brian left it very much up to me. With limited funds, I could not fly to Brasil, Riyadh, New York or travel to a cathedral way north of Stockholm, let alone get to Kazakhstan - all places which featured important work. (Pictured right, Lord Foster's Pyramid of Peace, Astana, Kazakhstan, with the apex by Brian Clarke © 2006 Brian Clarke)

Something about the way he had always spoken to me of a relatively modest project at a small 1,000-year-old church in Romont, near Fribourg in Switzerland, suggested to me that this was something I should definitely film. When I got there, met the nuns of the Cistercian abbey who had commissioned a series of windows from Brian 15 years ago, and experienced the work, I knew that this would, in all kinds of ways, provide a key moment in the film: the commission drew something from deep inside him, as the Abbess clearly recognised and talks about in the film in a moving sequence. In her terms, it is about communicating with the Invisible. In Brian’s, it’s about freeing his spirit, transcending ordinary reality and expressing something of the truth that lies behind it.

As Martin Harrison says in the film, “There is always in Brian’s work a mixture of order and chaos, the grid and the free line” - the punk-inspired artist who makes work in churches and shopping malls, the stained-glass artist who works for corporations and yet fights his ground at the expense of getting the commissions he doesn’t feel comfortable with, or many times going way over budget at his own cost. Harrison talks of the “free line” in Brian’s drawings, paintings and stained glass, as an expression of his free spirit: “It is a nervous line, it is his life.” The line is there from the start – it is the stuff of the drawing, an art at which Clarke (pictured left © Ti Foster) unquestionably excels.

As Martin Harrison says in the film, “There is always in Brian’s work a mixture of order and chaos, the grid and the free line” - the punk-inspired artist who makes work in churches and shopping malls, the stained-glass artist who works for corporations and yet fights his ground at the expense of getting the commissions he doesn’t feel comfortable with, or many times going way over budget at his own cost. Harrison talks of the “free line” in Brian’s drawings, paintings and stained glass, as an expression of his free spirit: “It is a nervous line, it is his life.” The line is there from the start – it is the stuff of the drawing, an art at which Clarke (pictured left © Ti Foster) unquestionably excels.

On one level the film tells the story of that line. Inspired by the German Johannes Schreiter, one of the great stained-glass artists of our times, Clarke sought ways of liberating the lead lines that were originally used to hold the pieces of glass together. He allowed it to become an independent element in the image. The liveliness and appeal of his work has a lot to do with witnessing this incredibly life-affirming release from formal constraints.

Clarke talks towards the end of the film about liberating the line entirely from the formal devices – the cross, fleur-de-lys and more recently schematised images of Spitfires, Porsches and paint tubes - that he has used to launch his imagination, and allowing it to assume a life of its own. This process has naturally taken him into sculpture, and the last thing I filmed, during the penultimate week of editing, was his first piece of bronze sculpture, fresh from the casting foundry in Stroud and not yet exhibited anywhere. There is a slightly oversized shiny-gold paint tube, around which dark "lines" that directly echo the work in his recent paintings reach upwards in a breathtaking mix of hesitancy and expressive direction. This piece, reflecting so much of Clarke’s character, is the logical outcome of his work in painting, drawing and glass.

All the media he has used - even if narrow-minded convention ascribes to them the label of "fine" or "applied" - are symbiotically related: there is no division between them. His reach across very different media has forced him into a parallel world. As Zaha Hadid says at the close of the film, “Brian is a very great artist. Fame is not what it’s about. The quality of the work is much more important.” Brian Clarke may be an underrated artist today but, as Zaha says, “His time will come.”

- Mark Kidel's film Colouring Light: Brian Clarke - An Artist Apart is on BBC Four on Monday, 17 October at 10pm

- Brian Clarke's website

- More information about Mark Kidel's films

Watch a clip from Colouring Light: Brian Clarke - An Artist Apart

![SEX MONEY RACE RELIGION [2016] by Gilbert and George. Installation shot of Gilbert & George 21ST CENTURY PICTURES Hayward Gallery](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_125_x_125_/public/mastimages/Gilbert%20%26%20George_%2021ST%20CENTURY%20PICTURES.%20SEX%20MONEY%20RACE%20RELIGION%20%5B2016%5D.%20Photo_%20Mark%20Blower.%20Courtesy%20of%20the%20Gilbert%20%26%20George%20and%20the%20Hayward%20Gallery._0.jpg?itok=3oW-Y84i)

Add comment