As a line flows or falters, registering each slight change in pressure, pause, or occasional reworking, it seems to offer a glimpse into the mind of the artist at work. The line is the instrument of the artist’s eye, the often unpolished, provisional nature of a drawing offering a spark and freshness that tends to gradually lessen as a composition is rethought and worked up in paint.

Portraits only intensify this sense of immediacy, and from likenesses of loved ones hastily dashed off, to awkward first sittings for a commission, such drawings offer an unparalleled sense of encounter with an artist of the past. While this makes it easy to fetishise drawings by quasi-mythical figures such as Leonardo and Rembrandt, instead of encouraging us to focus on their individual genius, this exhibition at the National Portrait Gallery plunges us into the cut and thrust of artistic life from the 15th to 17th centuries.

Blessedly free from wall texts, the works are arranged to highlight their function in the artists’ studios of the Renaissance, where drawing from the life was not just part of the process of portraiture but the backbone of painting practice. It was at the core of an artists’ training, and a practice that many artists today still consider to be an essential daily exercise, in the way perhaps that a musician might practice scales and arpeggios.

Blessedly free from wall texts, the works are arranged to highlight their function in the artists’ studios of the Renaissance, where drawing from the life was not just part of the process of portraiture but the backbone of painting practice. It was at the core of an artists’ training, and a practice that many artists today still consider to be an essential daily exercise, in the way perhaps that a musician might practice scales and arpeggios.

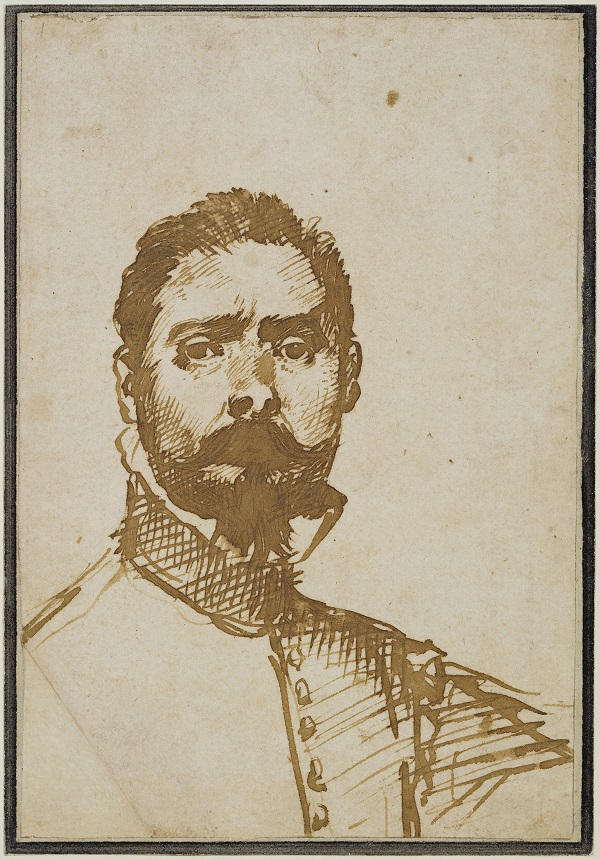

In the academy set up in Bologna by the Caraccis, drawing was an obsession, with any opportunity to take a likeness seized in a spirit of intense competition. The slightly frozen expression of one boy suggests that he has been ordered to "sit still!" by someone in authority, while the swaggering expression of the lutenist Mascheroni (pictured right) is matched by the bravado of the penmanship, the ink expertly controlled but threatening to run catastrophically. The waifish figure of a young man, accompanied by the inscription "I don’t know if God helps me" seems likely to be someone brought in off the streets; in the many characterful faces that populate the gallery walls there is a sense of artists constantly on the lookout for interesting people to draw, whether amongst friends, on the streets, or in the households of patrons.

While a formal, finished portrait would usually be completed in a way that showed the sitter to the best effect, most of these drawings are more for the artist’s satisfaction than the sitter’s, so that their nervous glances, or slightly bored expressions have been preserved on the page; surrounded by all these portraits, a self-portrait seems all the easier to recognise, the slight frown of concentration in that by Peter Oliver, c.1620, a dead giveaway. Some sitters verge on the hostile and the Old Woman Wearing a Ruff and Cap, c.1625-40, attributed to Jacob Jordaens fixes the artist with an unnerving glare (main picture).

In this exhibition, the curators point out, the drawings are still portraits, released temporarily from their usual categorisation as preparatory drawings for paintings. Sometimes, however, we see a model posed for a specific role, as in Pisanello’s study of one of his apprentices with his hands bound behind his back, a drawing that was used to model the figure of a hanged man in his fresco St George and the Princess, c.1434-8, at the church of Sant’ Anastasia in Verona.

In this exhibition, the curators point out, the drawings are still portraits, released temporarily from their usual categorisation as preparatory drawings for paintings. Sometimes, however, we see a model posed for a specific role, as in Pisanello’s study of one of his apprentices with his hands bound behind his back, a drawing that was used to model the figure of a hanged man in his fresco St George and the Princess, c.1434-8, at the church of Sant’ Anastasia in Verona.

Before an apprentice was allowed to draw from the life, he copied from the studio’s model books, the sheets of stock images that not only provided a much plundered source of figures and motifs for paintings, but also tutored studio assistants in the master’s style. He might copy from finished works too, as seen in a wonderful sheet of male and female heads copied from a range of different sources, including a painting by Veronese (pictured above). A sheet of heads from Hans Holbein the Elder's studio has been linked to several members of the Holbein dynasty, and to at least two finished paintings, the grotesque faces put to use as Christ’s tormentors.

Holbein figures prominently, and in sets of drawings made at the Tudor court, he encounters a whole range of different personalities, and you sense him putting them at ease, helping them find a comfortable way to sit. Woman Wearing a White Headdress, c.1526-8, has the slight smile of someone prone to nervous giggles, while the Man Wearing a Black Cap, c.1535, has slipped into his own thoughts, his eyes cast down as if avoiding the artist’s eye. They are astonishing pictures to look at, in an exhibition that offers a vivid and unexpected glimpse into the studios of the past.

- The Encounter: Drawings from Leonardo to Rembrandt at the National Portrait Gallery until 22 October 2017

- Read more visual arts reviews on theartsdesk

Add comment