Harry Potter has a track record of trickery. He miraculously persuaded a generation of screen addicts to get stuck into hardbacks. Lately he has been luring multiplex junkies into the theatre to see live wizards on stage. Can Harry Potter make it a hat trick by coaxing his fans into a gallery? Harry Potter: A History of Magic is at the British Library. “I’ve got to get to the library!” says Hermione Grainger on the inside flap of the exhibition book. Is a trip to this library obligatory?

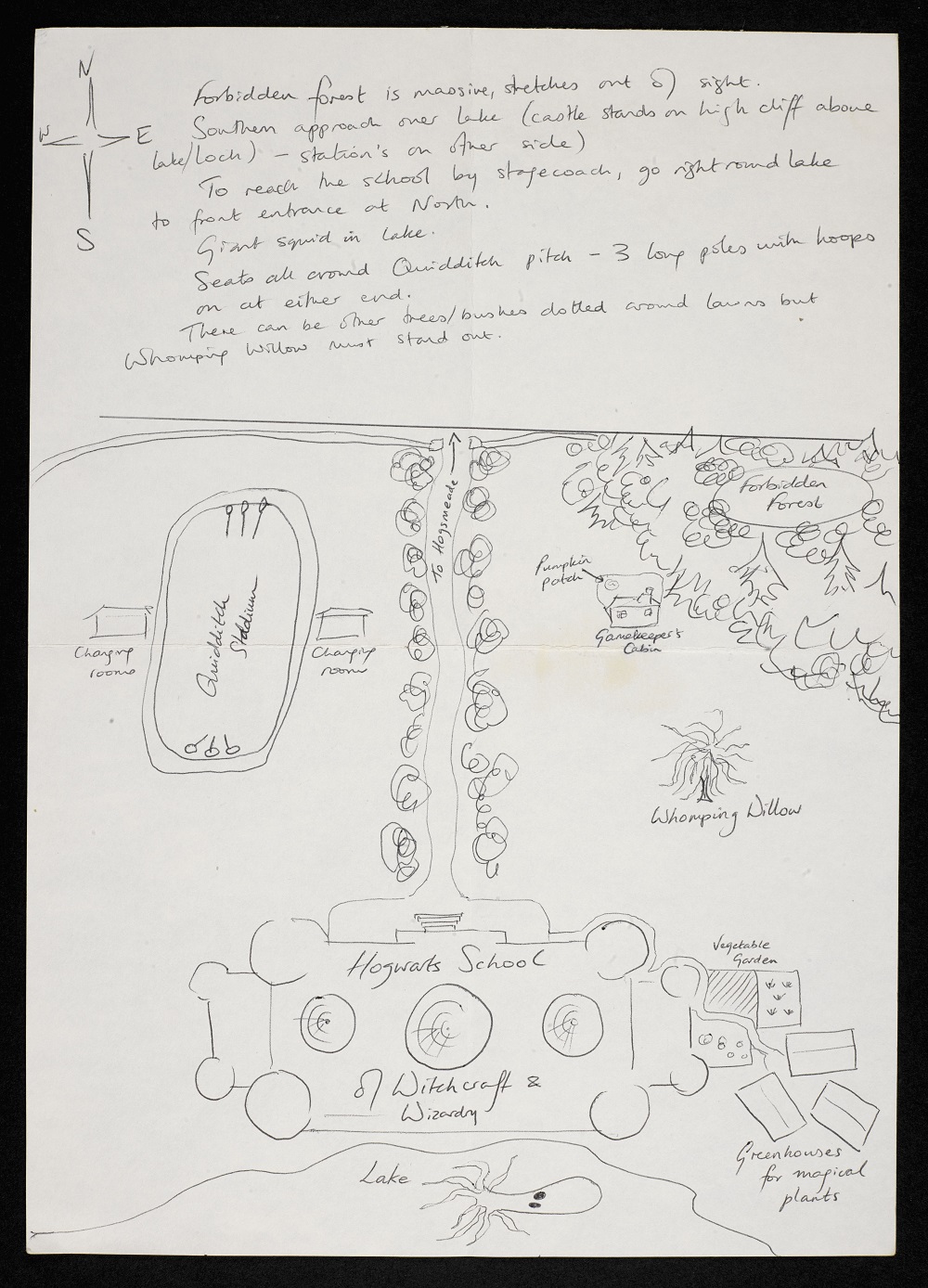

The show is astutely pitched at younger gallery-goers. For one and a half days a week, you won’t be able to get in unless you’re in a school party (sections of it will be displayed on panels in 20 public libraries in the UK). The bait is a sizeable loan from JK Rowling, including handwritten drafts, proofs, a scribbled map of Hogwarts (pictured below © JK Rowling), a guide to the sorting hat, a gridded plot plan of Harry Potter and the Order of the Phoenix, on which one panel reads in fanfaring capitals, “DOESN'T REALISE UNTIL THERE THAT THE HALL CONTAINS PROPHECIES”. The real surprise from Rowling is a set of her own sketches of her characters (including Nearly Headless Nick and the squib Argus Filch). These illustrations were made several years before the first book’s publication. Hermione, it should be noted, has big curls. There is also an annotated first edition of Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone. The story of how she wrote the book, she says, “is written invisibly on every page, legible only to me.” Talking of invisible, a certain cloak hangs from a thick hook in a display case.

The real surprise from Rowling is a set of her own sketches of her characters (including Nearly Headless Nick and the squib Argus Filch). These illustrations were made several years before the first book’s publication. Hermione, it should be noted, has big curls. There is also an annotated first edition of Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone. The story of how she wrote the book, she says, “is written invisibly on every page, legible only to me.” Talking of invisible, a certain cloak hangs from a thick hook in a display case.

If this exhibition is to be a gateway drug for Potterheads, they’ll need to get used to po-faced gallery labels. One next to a draft of text about Professor Quirrell explains that the author was “writing in biro, on unlined paper”. When in Rome... Never in her wildest fantasies can Rowling have imagined being exhibited alongside Leonardo da Vinci, but here they both are: a page from one of Leonardo's notebooks illustrates the sun and moon revolving around the Earth; in this context his mirror writing has a sulphurous whiff of necromancy.

It’s a bizarre and sometimes jarring experience wandering along display cases which include material from the 1990s alongside items of ancient vintage. One or two exhibits are staggeringly old. Some Chinese oracle bones are from before 1000 BC. There’s also a real cauldron from the Bronze Age, the so-called Battersea Cauldron (pictured below © Trustees of the British Museum) which could be more than 3000 years old, alongside a real broom, a real bezoar, a real mandrake (very creepy). The oldest books date back to the start of the last millennium: from the 12th century a book offers a remedy for snakebite from a plant known as Centaury, and an astronomical miscellany illustrates the dog-shaped constellation Canis Major (aka Sirius). An opening video interview with Rowling sort of disavows almost everything that follows: 95 percent of the magic in her books is made up, she attests. On the other hand, you could argue that 100 percent of all magic is made up, however integral to a wide panoply of cultures. The show is divided into sections which match subjects studied at Hogwarts (herbology, potions, care of magical creatures etc). What they cumulatively stress is that Rowling may have invented the spells, but her background knowledge was profound.

An opening video interview with Rowling sort of disavows almost everything that follows: 95 percent of the magic in her books is made up, she attests. On the other hand, you could argue that 100 percent of all magic is made up, however integral to a wide panoply of cultures. The show is divided into sections which match subjects studied at Hogwarts (herbology, potions, care of magical creatures etc). What they cumulatively stress is that Rowling may have invented the spells, but her background knowledge was profound.

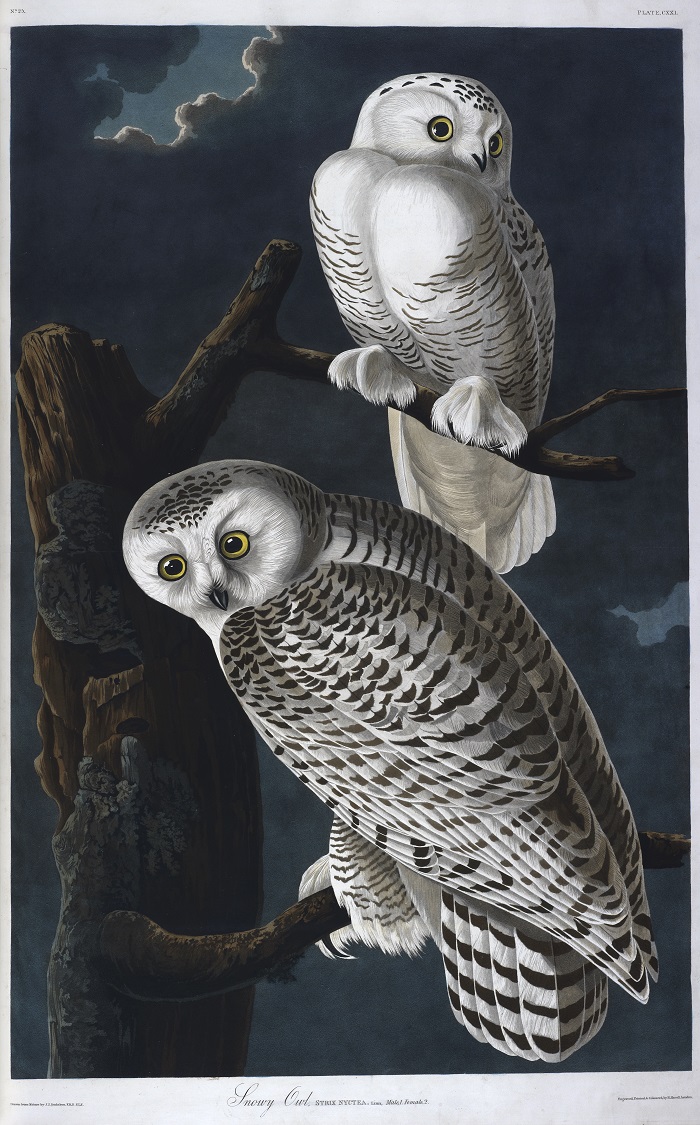

Thus we meet the real Culpeper and the real Nicolas Flamel – his 15th-century tombstone is even here. The remarkable 16th-century Ripley Scroll, six metres long, explains how to follow Flamel’s lead and create a philosopher’s stone. Not all of this is going to hit the spot with many 10- or even 20-year olds. But in and among the rather dry text-based exhibits that might struggle to ignite younger minds, there are many such visual coups. Two stunning life-size snowy owls stare out from John James Audubon’s 19th-century The Birds of America (pictured below © British Library Board). There’s a beautiful double-page illustration of a reticulated python from 18th-century Holland. Among the many apothecary manuals, there’s Robert Thornton’s The Temple of Flora (1799-1807), a vast tome on which the page is open on a livid-looking Drago Arum: “This extremely foetid poisonous plant will not admit of sober description,” he advises. In John William Waterhouse’s highly dramatic painting The Magic Circle, 1886, a wild-eyed enchantress draws a protective circle around herself with a wand.

The global footprint of the collection is impressive: as well as China and the Americas, there are exhibits from as far afield as Ethiopia, Iran and Egypt, but also plenty of tongue-in-cheek items borrowed from the Museum of Witchcraft in Boscastle, north Cornwall, which has lent a leaky cauldron dated to 1998. Other inducements are Jim Kay’s portraits of characters and places for Bloomsbury's illustrated editions; the highlights are some fetching sketches of winged keys and a dense visualisation of Diagon Alley.

The global footprint of the collection is impressive: as well as China and the Americas, there are exhibits from as far afield as Ethiopia, Iran and Egypt, but also plenty of tongue-in-cheek items borrowed from the Museum of Witchcraft in Boscastle, north Cornwall, which has lent a leaky cauldron dated to 1998. Other inducements are Jim Kay’s portraits of characters and places for Bloomsbury's illustrated editions; the highlights are some fetching sketches of winged keys and a dense visualisation of Diagon Alley.

If the Potter phenomenon is a triumph of fantasy over rationalism, its magical world is rooted in real fears and beliefs. There are images of witches from medieval England and werewolves in a 16th-century book from Strasbourg are said to enjoy the taste of children. A 17th-century pharmaceutical manual depicts five types of unicorn including "three unidentified breeds" and recommends the horns as an antidote to poisons.

But not all creatures were magical. From 1699 to 1701 a naturalist called Maria Sybilla Merian became the first woman ever to lead a scientific expedition. In Surinam she encountered a giant spider that feasted on birds, and illustrated them beautifully. When she got home to Amsterdam she was discredited by male peers who dismissed her a fantasist (her findings were accepted only in 1863). There's nothing wrong with being a fantasist, of course, as this weirdly wonderful exhibition demonstrably proves.

- Harry Potter: A History of Magic at the British Library until 28 February 2018. It travels to the New-York Historical Society in October 2018

- More visual art reviews on theartsdesk

Add comment