Unswervingly confident, relaxed and assured, the élite of the 18th century are currently arrayed on the walls of the Royal Academy, gazing down at us with the utmost assurance of their unassailable place in the world, bright eyed and dressed to match. The swirls of public reputation are unpredictable: here is a revelation, the art of one of the most successful and highly prized portraitists of his day, Jean-Etienne Liotard (1702-1789), now almost completely unknown except to specialists.

A Huguenot, born in the independent Protestant city state of Geneva, he trained in Paris, and went on to travel all over Europe, visiting his clientele, having first in Italy joined the milordi and the grand tourists and accompanied them east to the Levant. He spent four years in Constantinople, absorbing the visual pleasures of the exotic, then to the court of Moldavia (present day Romania), Vienna, Germany, back to Paris for seven years, then London, Holland, and so on, through central and western Europe, painting as he went. Often dressed à la Turque himself, and with a luxuriant beard down to his waist, he excelled at self promotion, as Sir Joshua Reynolds grumbled.

Each portrait, whether drawing, miniature, oil painting or pastel, convinces as much by the gleaming textures of lace, satin and velvet, as the charming faces, vibrantly alive. In his time he was, as his contemporaries put it, the esteemed “painter of truth”, a magician in oil and pastel – yet his art has escaped public scrutiny until now. In part this is explained by his clientele, for much of what he did for grandees, not to mention the royals – Habsburgs, Bourbons and Hanoverians – has remained in private collections. And although he was an accomplished draughtsman, miniaturist and painter, much of his work is pastel, that most delicate of media (on vellum, and sometimes on paper) which, until recently, was very difficult to transport and show easily. Pastel, practical as it is easy to transport in its crayon-like sticks, is nevertheless a powdered pure pigment bound with gum and if treated carelessly reverts to just that, powder.

The sheer mastery with which these privileged people are portrayed is hypnotically fascinating. Moreover he had a rare sympathy for children, his own and others, still as was the convention of the day treated as miniature adults and dressed as such. But he catches their delicate, wary curiosity and the hints of the adult to come with an empathetic eye. The heartbreakingly tender and candid portrait of Princess Louisa Anne, five-year-old daughter of the Princess of Wales, was painted in 1754. She is wearing a dress too big for her, her right nipple showing, and her fragility is apparent in the silvery rather than rosy glow to her skin; she was dead by 19, of tuberculosis, that scourge even of the most privileged. (Pictured above right: Julie de Thellusson-Ployard, 1760; Pastel on vellum; Museum Oskar Reinhart, Winterthur)

The sheer mastery with which these privileged people are portrayed is hypnotically fascinating. Moreover he had a rare sympathy for children, his own and others, still as was the convention of the day treated as miniature adults and dressed as such. But he catches their delicate, wary curiosity and the hints of the adult to come with an empathetic eye. The heartbreakingly tender and candid portrait of Princess Louisa Anne, five-year-old daughter of the Princess of Wales, was painted in 1754. She is wearing a dress too big for her, her right nipple showing, and her fragility is apparent in the silvery rather than rosy glow to her skin; she was dead by 19, of tuberculosis, that scourge even of the most privileged. (Pictured above right: Julie de Thellusson-Ployard, 1760; Pastel on vellum; Museum Oskar Reinhart, Winterthur)

The artist’s own eight-year-old daughter, Marianne, dressed delightfully in blue, yellow and white, holds her china doll, also dressed in yellow and blue, and holds her finger up in the time honoured signal to keep quiet; her doll albeit with eyes wide open is evidently asleep.

There is an element in Liotard of beautifully costumed posing, the public persona rather than the private, although not with his views of children. He doesn't of course have the psychological penetration of, say, Goya – who does? – but within the limits of his chosen profession he was a master.

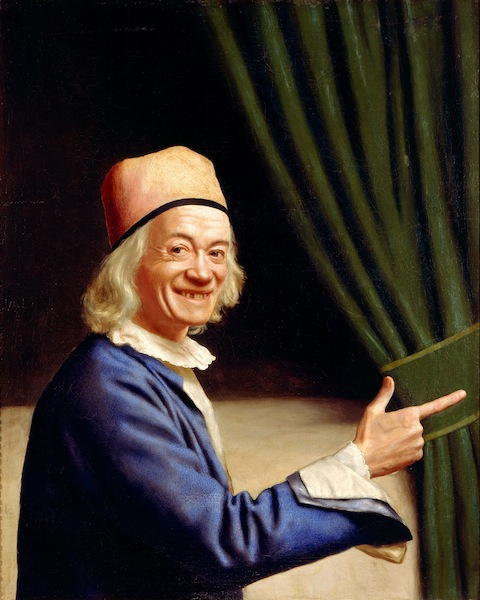

A late self portrait has him in a deep blue jacket, shining white shirt plus ruffled collar, and yellow cap, a model of restraint, but the miniature of Laura Tarsi has her dressed to kill: triple layers heavily embroidered, almost gilded, and a bejewelled turban. And imaginative male dandies include William Ponsonby, Lord Duncannon, an early and loyal patron,dressed in exotic Turkish costume, all in red, with fur-trimmed dark robe, complete with matching turban, gold sash and scimitar. Duncannon’s wife wears a dress so heavily embroidered with marvellous flowers that it seems to have a life of its own, engulfing its wearer.

The images are utterly charming, and can be ruthlessly realistic in terms of facial characteristics. Double chins abound. Here is the illegitimate but very rich Harriet Churchill, Lady Fawkener, wrapped in black lace over a sumptuous white gown, and with a charming hat, but certainly plain. One of his most privileged but tragic sitters was Charlotte Boyle, one of England’s greatest heiresses, married at 16 to the Marquess of Hartington. Here she is in a fur-trimmed gleaming blue cape. Her unusually large nose is eye-catching, and her red cheeks may indicate the incipient smallpox of which she was dying, aged only 23.

In his eerily odd self portrait (pictured left: Self-portrait Laughing, c.1770; Musee d'art et d'histoire, Geneva) he shows himself in his 60s with wrinkled and leathery skin, and a big gap where there is a missing front tooth. Uncharacteristically unconventional he is smiling with his mouth open, usually not an option in portraiture because of the appalling state of 18th-century dentistry, no matter your social class.

In his eerily odd self portrait (pictured left: Self-portrait Laughing, c.1770; Musee d'art et d'histoire, Geneva) he shows himself in his 60s with wrinkled and leathery skin, and a big gap where there is a missing front tooth. Uncharacteristically unconventional he is smiling with his mouth open, usually not an option in portraiture because of the appalling state of 18th-century dentistry, no matter your social class.

But Liotard’s own worn skin is an exception. What provides a kind of inner light in most of these portraits that almost invariably everybody’s skin is luminous, pearlescent, even flawless.

Liotard was the master chronicler in line and colour of many of the leading characters of his time.This unprecedented collection of his work could not be a more beguiling glimpse of the age of reason and of enlightenment, foreshadowing too, in this display of privilege, the coming of revolution.

Add comment