You wouldn't judge a painting on how it would look in your own home, but textiles are different: in fact it is exactly this assessment that counts. A length of fabric laid flat is a half-formed thing: it needs to be cut, stitched and draped before we can appreciate it, and even then it must take its place within an interior, domestic or public, before we can really understand it. Fabrics need – to coin a terrible, but useful expression – to be activated.

There are examples of John Piper’s textile designs, like Arundel (1959, issued 1960), that look rather wonderful framed and treated like pictures, but most of the furnishing fabrics in this exhibition, realised by venerable British manufacturers like Arthur Sanderson & Sons Ltd and David Whitehead Ltd, are at a serious disadvantage. Hung on walls with no real indication of their application, they are viewed in a raw, and effectively incomplete state – and on this basis, I wouldn’t give house space to any of them.

And yet I'm sure I’ve missed something. Piper was prolific, producing multiple designs, often in a range of colourways. Clearly they were hugely popular, and as current tastes are very much in tune with mid-century design, it is surprising to find them so utterly unappealing. But aside from a sample hung from a curtain rail, we really don’t get any impression of what these fabrics were like as furnishings. The Glyders, issued by Sandersons in 1960, was a favourite in the Piper household, but what we really need is to see it made into a chair covering.

And yet I'm sure I’ve missed something. Piper was prolific, producing multiple designs, often in a range of colourways. Clearly they were hugely popular, and as current tastes are very much in tune with mid-century design, it is surprising to find them so utterly unappealing. But aside from a sample hung from a curtain rail, we really don’t get any impression of what these fabrics were like as furnishings. The Glyders, issued by Sandersons in 1960, was a favourite in the Piper household, but what we really need is to see it made into a chair covering.

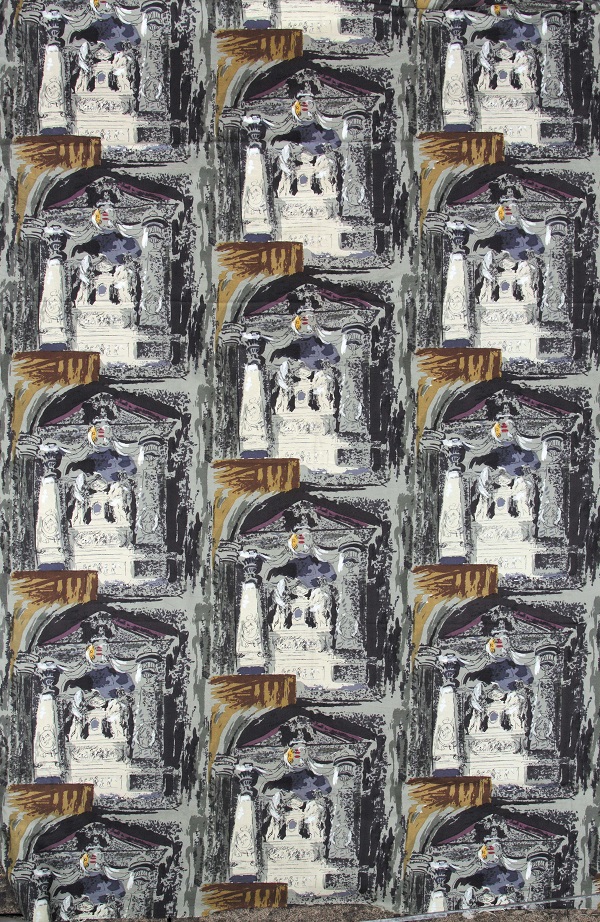

Not all of Piper’s designs were for upholstery fabrics, and the earliest piece here is an Ascher square from 1947, one of a series of silk scarves designed by artists including Picasso, Matisse, and Hepworth. Piper’s Medieval Heads design reflects his preoccupation with stained glass and the ancient heritage of Britain, a theme that recurs in his textile designs, many of which include motifs of church buildings and landscapes, treated in a modernist idiom (pictured above right: Church Monument, Exton, 1954).

A pioneer of abstraction in the 1930s, Piper had returned to landscape by the 1940s, and in his role as an official war artist he toured Britain recording the bombed remains of churches and cathedrals from Coventry to Bath and London. Peers like Barbara Hepworth and Ben Nicholson were aghast at what seemed to be his rejection of modernism, but however much Piper’s work in the Forties and Fifties seems nostalgic, a melancholic yearning for a lost past, it is always tempered with a modern edge, his Foliate Heads owing as much to Picasso as the medieval stonemason (main picture).

His paintings from this period look much like the fabrics, and Piper's loose brushstrokes and vibrant colour combinations foster pattern and symmetry, promoting a sense of movement ideally suited to fabric. Indeed, many of the fabric designs originated as paintings. What is not entirely clear is whether the paintings were made with a fabric design in mind, or whether paintings originally made as autonomous objects were later identified as a suitable source for a fabric.

Piper’s painting Sheffield Cathedral, 1960, is clearly the source for Sanderson’s Northern Cathedral design issued in 1962, and yet the considerable differences between them suggest that while the painting might have served as the initial inspiration for the fabric, it did not form part of a conscious design process. The painting consists of two distinct fields, the cathedral represented in a dark area that contrasts with the vivid reds of a neighbouring brick building. In the fabric, these fields have been lightened considerably, and treated as repeating, contrasting motifs that would be particularly effective when gathered.

Despite various comparisons of paintings and fabrics, the process of translation from paint to cloth is not really explored, and there is little sense of the process of collaboration that must have occurred. Piper described his textile designs as “delegated art”, but the craftsmen and women who realised his designs remain largely invisible. The closest we get to insight into the process of delegation concerns the Chichester Tapestry, which hangs behind the cathedral’s High Altar and was consecrated 50 years ago in 1966.

Despite various comparisons of paintings and fabrics, the process of translation from paint to cloth is not really explored, and there is little sense of the process of collaboration that must have occurred. Piper described his textile designs as “delegated art”, but the craftsmen and women who realised his designs remain largely invisible. The closest we get to insight into the process of delegation concerns the Chichester Tapestry, which hangs behind the cathedral’s High Altar and was consecrated 50 years ago in 1966.

Made up of seven separate panels, the tapestry is an abstract but essentially figurative design that reflects Piper’s return to abstraction in the Sixties, and his use of techniques like collage and marbling (pictured left: Cartoon for St Luke, Chichester Cathedral Tapestry, 1965). The tapestry was woven by Pinton Frères in the Limousin region of France, and while the weavers translated Piper’s strips of marbled paper with remarkable accuracy, other areas have been interpreted more freely, staying faithful to a general effect rather than fastidiously replicating marks on paper. But while we know that Piper worked closer with the Pinton Frères, and immersed himself fully in the challenge of designing a tapestry, it is hard to gauge to what extent Piper was engaged with the technical problems of the project, and whether he confined himself to artistic challenges.

The purpose of this exhibition is to show the relationship between Piper’s textile designs and his broader practice, but bound up with this is the far more compelling question of process, which is disappointingly under-explored. What we have instead is a snapshot of a special area of creative endeavour, when artists saw textile design as a vehicle for the democratisation of art in a post-war utopia.

- John Piper: The Fabric of Modernism at Pallant House Gallery, Chichester until 12 June

![SEX MONEY RACE RELIGION [2016] by Gilbert and George. Installation shot of Gilbert & George 21ST CENTURY PICTURES Hayward Gallery](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_125_x_125_/public/mastimages/Gilbert%20%26%20George_%2021ST%20CENTURY%20PICTURES.%20SEX%20MONEY%20RACE%20RELIGION%20%5B2016%5D.%20Photo_%20Mark%20Blower.%20Courtesy%20of%20the%20Gilbert%20%26%20George%20and%20the%20Hayward%20Gallery._0.jpg?itok=3oW-Y84i)

Add comment