During morning and evening rush hour, Bamako seizes up under the pressure of all the cars, motorbikes, trucks and buses, bringing the three bridges over the Niger River to a standstill and testing Mali’s reputation for patience and humour to its limits. From a mere 130,000 at independence in 1960, the population of the city has now ballooned to over three million. Every week, thousands of refugees fleeing violence in the rest of the country, two thirds of which is effectively in a state of anarchy, move into crowded camps on the outskirts. It’s a miracle that the city functions at all. But it does, with surprising grace.

Most Bamakois travel on the green minibuses known as SOTRAMAs, easily recognisable by the bags piled on their roofs, the young fare-collectors hanging precariously from their rear ladder, the religious and moral slogans daubed over their dilapidated bodywork. In March 2022, the Malian Association of Female Photographers acquired their own SOTRAMA bus and turned it into a mobile photographic studio, with lights, printer and a black and white checked backdrop reminiscent of the one used by the famous Malian photographer Malick Sidibe (main picture). The bus visits SOTRAMA hubs in far flung neighbourhoods of city and further afield to take portraits of ordinary travellers, who are sent home with a souvenir print. As an answer to the perennial challenge of getting ordinary citizens involved in the art of photography, the idea is pure genius.

"Malians have always loved photography," says Fatoumata Diabaté, president of the Association of Female Photographers and a world-renowned photographer in her own right (pictured right). "Even before the arrival of digital, we would make ourselves look beautiful and go and see a photographer to make some portraits, then take them home. Every family has their family album. Now everyone has their telephones and their selfies, but no one has great prints of themselves."

"Malians have always loved photography," says Fatoumata Diabaté, president of the Association of Female Photographers and a world-renowned photographer in her own right (pictured right). "Even before the arrival of digital, we would make ourselves look beautiful and go and see a photographer to make some portraits, then take them home. Every family has their family album. Now everyone has their telephones and their selfies, but no one has great prints of themselves."

Diabaté is one of the more than 75 photographers exhibiting at the 2022-23 Rencontres de Bamako: The Biennale of African Photography. She cuts a regal presence in her opulent red headdress as she introduces the SOTRAMA Project to a group of curators, journalists and photographers at the National Museum of Mali on a hot afternoon in late December. Some of her own work is on show in the adjoining hall, large scale portraits of figures with their faces hidden behind a surreal mishmash of masks wearing explosively coloured clothes, an old fashioned alarm clock in every image making an oblique illusion to the pandemic and its slowing down of time. "The Biennale is a beautiful opportunity for Mali." she says. "It’s inspiring."

A beautiful opportunity and, by all accounts, a nightmarish organisational feat. Launched in 1994, the Biennale is not only the oldest but also the biggest festival of photography on the African continent. As such, it’s no stranger to existential headaches and sleepless nights. Previous editions have been cancelled or marred by Islamist violence and this latest edition, the 13th, was slated to take place at the end of 2021 but had to be postponed several times thanks to the pandemic, economic uncertainty and Mali’s second military coup in as many years. Its organisers faced obstacles that would have tipped festival promoters of lesser mettle over the brink of nervous breakdown: foreign embargoes, crumbling relations between Mali and France (the French Institute in Bamako has been a key Biennale partner from the beginning), the late arrival of promised funds, Mali’s reputation as a dangerous place for foreign travel, the difficulty of engaging volunteers in a country where the average salary is less than $100 a month, baggage handling chaos at Bamako airport and the list goes on.

When I sit down to chat with the Biennale’s artistic director, the Cameroonian curator Bonaventure Soh Bejeng Ndikung, he respectfully requests that I focus on the positives, number one being that the Biennale continues to exist at all. ‘We’re here in Mali, a country where living and working is difficult, and we managed to deliver this exhibition, bring over 70 artists and journalists and display work in eight venues throughout Bamako. We also did all the printing, over 1000 photos, here in Mali, to support the artistic ecosystem of the country. That’s already a success. It wasn’t easy.’

Given its bare-knuckle struggle for survival, the Biennale’s insistence on striving for and achieving excellence feels almost hubristic. ‘In comparison with other big photographic gatherings, like [the Rencontres d’]Arles, Fotofest Houston or ParisPhoto, the quality and the integrity of the work here is remarkable,’ says veteran British photographer Joy Gregory. ‘It knocks all those other festivals out completely. There’s no weak work anywhere to be seen. And the thing that’s amazing is that all of Africa is here, in all its diversity.’

Given its bare-knuckle struggle for survival, the Biennale’s insistence on striving for and achieving excellence feels almost hubristic. ‘In comparison with other big photographic gatherings, like [the Rencontres d’]Arles, Fotofest Houston or ParisPhoto, the quality and the integrity of the work here is remarkable,’ says veteran British photographer Joy Gregory. ‘It knocks all those other festivals out completely. There’s no weak work anywhere to be seen. And the thing that’s amazing is that all of Africa is here, in all its diversity.’

Gregory is one of four long-established African and African Diaspora A-listers invited to show their work alongside the 70 younger or less well-established photographers who were picked from over 150 submissions (pictured above left: Joy Gregory, Over Shoulder Complete). The other veterans are the Cuban photographer Maria Magdalena Campos-Pons, the Moroccan Daoud Aoulad-Syad and the South African Jo Ratcliffe. For Gregory, attendance was in part a matter of defying all the fearful headlines and showing compassion for a country that was, until relative recently, considered one of the safest and most welcoming places in Africa. "It was really important to be here to show solidarity," she says. "Culture’s really important, and when a country’s being decimated or going through a difficult time, I think culture is the thing that pulls it through."

One of the advantages of apprehending Africa through its culture, rather than through poverty, disease, corruption, conflict–the usual conduits for the Western mind–is the lack of pity involved. Culture demands a curious, eager and respectful engagement, one that binds consumer and provider in mutually beneficial relationship. Culture draws you in; pity keeps you at a distance. And being drawn in opens up a wondrous human complexity that stymies all the clichés and the givens: Mali equals deprivation, Mali equals conflict, Mali equals Islam gone rogue, Mali equals danger. Those are mere headlines. The small print of life here is far more complex, multi-layered, elusive, seductive.

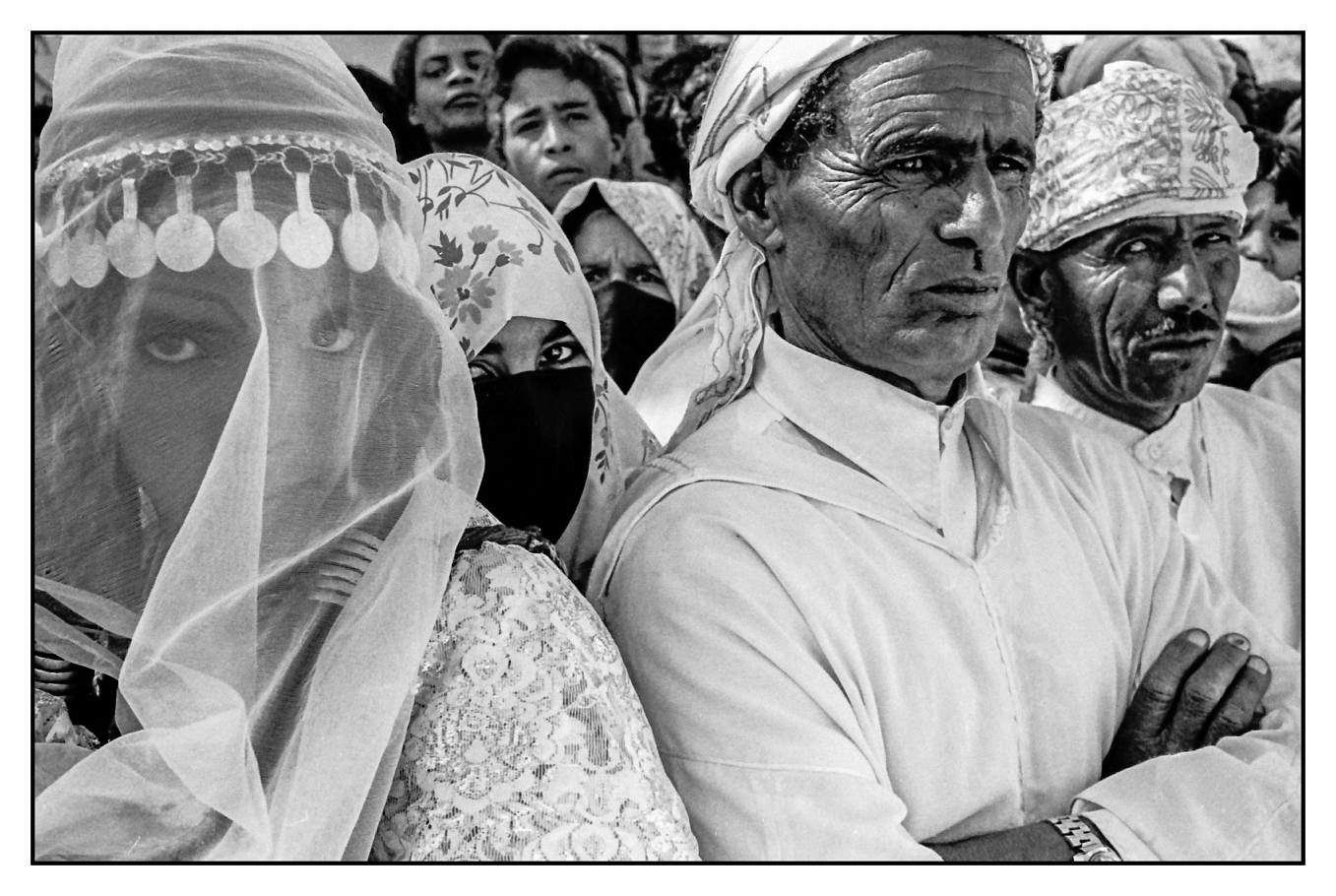

Aoulad-Syad, with his genial smile and unruly thicket of greying hair, leaves the hotel early every morning to wander around Bamako and take pictures. He tells me that Bamako is a relatively easy place to practice his art, unlike Morocco, where people are often very suspicious of a Moroccan who dares to take pictures of other Moroccans. He’s exhibiting images from his seminal photobook Marocains, a bold attempt to retrain Robert Frank’s lucid and merciless brand of realism on a country that has long been the victim of bland dishonesty when it comes to photographic representation. Aoulad-Syad slices through all the orientalist fantasies with close-ups of his fellow countrymen and women caught in the mundane thick of their lives, with their tired, wary, embattled stares, their unselfconscious dignity and beauty (pictured above).

Aoulad-Syad, with his genial smile and unruly thicket of greying hair, leaves the hotel early every morning to wander around Bamako and take pictures. He tells me that Bamako is a relatively easy place to practice his art, unlike Morocco, where people are often very suspicious of a Moroccan who dares to take pictures of other Moroccans. He’s exhibiting images from his seminal photobook Marocains, a bold attempt to retrain Robert Frank’s lucid and merciless brand of realism on a country that has long been the victim of bland dishonesty when it comes to photographic representation. Aoulad-Syad slices through all the orientalist fantasies with close-ups of his fellow countrymen and women caught in the mundane thick of their lives, with their tired, wary, embattled stares, their unselfconscious dignity and beauty (pictured above).

The sub-title of this year’s Biennale is a quote by the famous Malian writer, philosopher and man of letters Amadou Hampâté Ba: maa ka maaya ka ca a yere kono. That’s Bamanan for "the persons of the person are multiple in the person", a tongue twister that basically asks us to consider and respect the mille-feuille of stories, experiences, opinions, desires, histories and aspirations that go to make up every human being, African or otherwise. It is fair to say that issues of multiplicity, difference and complexity are at the crux of Africanness, goes the Biennale’s mission statement. If we have survived the countless malicious and clamant snares which have been set up for us in the past hundreds of years, it is thanks to our ability to exist as multiple beings. To constantly morph from one being to another.

With this in mind, the curators have favoured photographers who tell complex stories that delve into personal, familial and national histories, and stories that honour the voiceless, especially women. Leo Asemota from Benin evokes Britain’s sacking of his country in 1897 in a grid of small polaroid snaphots, each one depicting a head and shoulder shot of a figure whose face has been reduced to pale nothingness. The effect is haunting, a vengeful chorus from a nightmare intoning the lament of stolen heritage and loss of humanity. Anna Binta Diallo, born in Senegal and raised in Canada, renders the concept of multiplicity in very graphic and immediate way with her composite beings, made up from scraps of earth and star maps, images of plants and planets. The individual layers are indecipherable, but together they convey an impression of human galaxies, constellations of experience, journey, myth, spirit, folklore that aren’t worth of interpretation so much as wonder. Laetitia Huckaby’s series Bitter Waters Sweet honours a group of enslaved West Africans who travelled to the American just before emancipation and founded the community of Africatown near Mobile, Alabama. The images - a lonely expanse of sea, the quiet suspicion of a virgin swamp, the shadow of a woman against antique flowery wallpaper - are populated by ghosts unseen but viscerally felt. Their power awakens a sixth sense and draws you into a tragedy hidden by an evaporating veil of silence and forgetfulness.

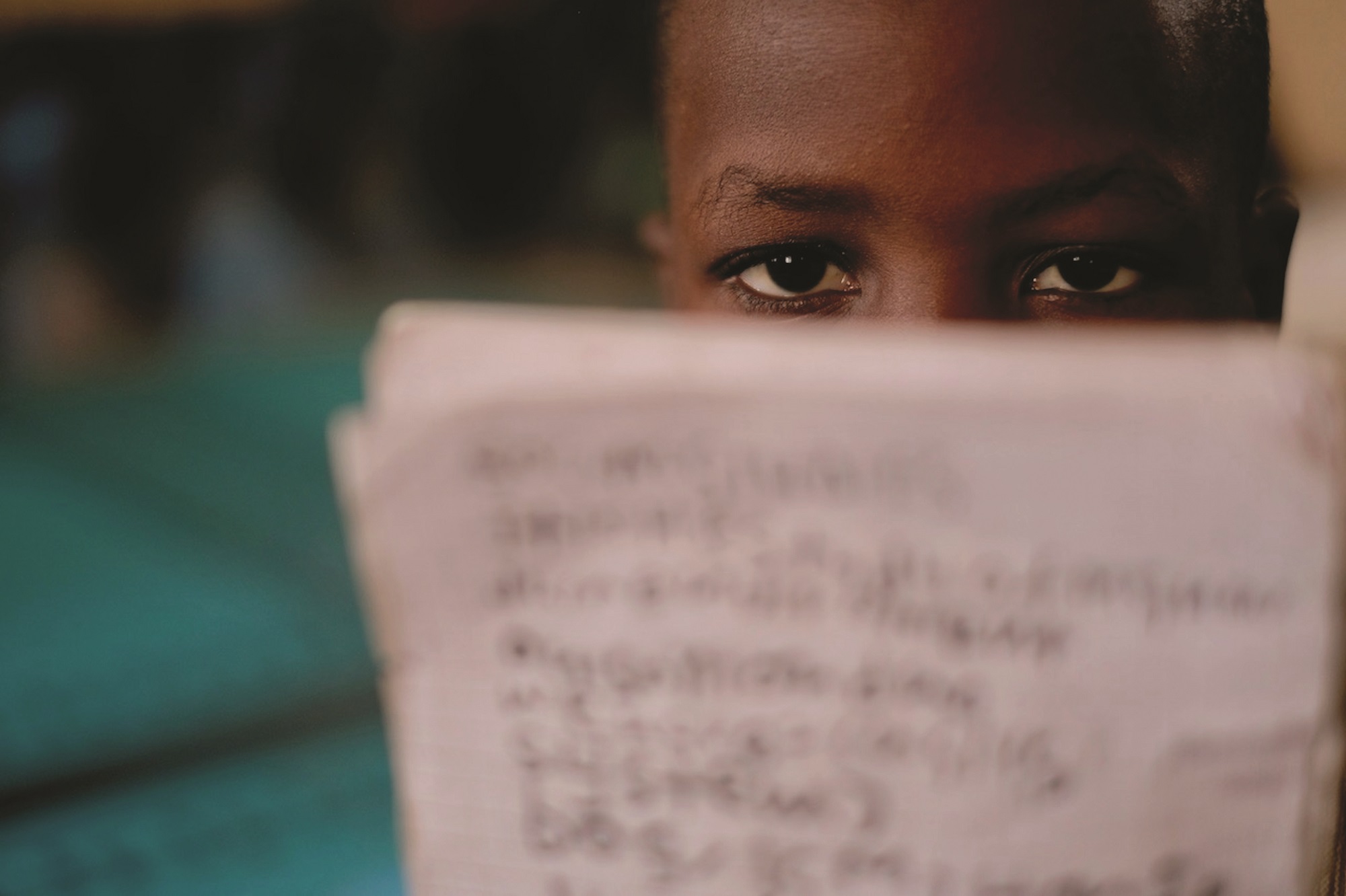

Renowned Nigerian documentarist Babajide Adeniyi-Jones tenderises the post-traumatic struggles of old and young in images of shadowy grief (pictured above): a veteran of Kenya’s Land and Freedom Army holding up fingers mutilated by British torture, his defiant eyes and forehead softened by the shallow depth of field; a grandmother staring into space as she struggles to stuff the recent kidnapping of her grand-daughter into an casket of memories already weighty with hardship; a seventeen year-old woman cradling a baby girl conceived through rape while in captivity, faintly delineated by the light streaming in through parted curtains. His dark, muted colours impose silence and his chiaroscuro illuminates small slithers of sadness in the gloom, drawing out compassion.

Renowned Nigerian documentarist Babajide Adeniyi-Jones tenderises the post-traumatic struggles of old and young in images of shadowy grief (pictured above): a veteran of Kenya’s Land and Freedom Army holding up fingers mutilated by British torture, his defiant eyes and forehead softened by the shallow depth of field; a grandmother staring into space as she struggles to stuff the recent kidnapping of her grand-daughter into an casket of memories already weighty with hardship; a seventeen year-old woman cradling a baby girl conceived through rape while in captivity, faintly delineated by the light streaming in through parted curtains. His dark, muted colours impose silence and his chiaroscuro illuminates small slithers of sadness in the gloom, drawing out compassion.

Mixed in with historical and archival quests are journeys into family mythologies and personal loss. Tunisian Maya Louhichi’s work And In The Land, I Remember is a poem of longing to the memory of her father in raw black and white: a close up of a woman’s thousand yard stare, a tender hug of self-compassion, a rumpled sheet and the plam of a hand ruffled like the surface of a lake that refuses to be stilled. The mood hipnotizes with its stripped-down intensity, laying a heart bare in its darkest moment. Arsène Mpiana Monkwe from Kinshasa, DRC, explores the myths of his clan, the Monkwe, and identities perverted and obscured by the colonial enterprise. Archival images and other documents are captured floating in water, distorted by ripples, drifting over fallen leaves, through the past darkly. When Mpiana almost drowned after jumping from a dugout into the Ndjili river, his father told him of his ancestral connection with crocodiles, the totem of the Monkwe, guardian protectors who guided the hand that saved him and guide his hand as he strives to save memory from watery oblivion.

The voiceless are ushered into the light in Ebti Nabag’s study of Khartoum’s tea-sellers (pictured right). Tea-drinking is an essential daily pleasure that lubricates Sudanese life, and Nabag’s portraits gently call on us to honour these women at the bottom of the social heap, often refugees from neighbouring countries, who make that pleasure possible. The struggle to survive in a patriarchal world of economic hardship, inflation, corruption, is etched on their faces, alongside a quiet strength, a resilience that has been dearly bought. The village of Kahwet el Rih in Algeria, where many inhabitants are blind or partially sighted, is prised open in the stark black and white images of Fethi Sahraoui. Nobody really knows the origins of their sightlessness: a genetic flaw, the flying thorns of the Barbary fig, the djinns? Sahraoui’s eye doesn’t seek answers but rather a compassionate understanding of their marginal lives. He’s very conscious of the need to tread lightly in a place that many of its own inhabitants cannot see themselves, and to imagine the workings of their ‘second’ eye, the one that dreams and reconstructs sight out of pure imagination.

South Africa’s not seen and not heard are given the eye in Elijah Ndoumbe’s series Smoke Signals (A Quiet Song), a deep dive into the lives of Cape Town’s transgender and queer sex workers. The images avoid aggrandising, overblowing or pitying but rather capture fleeting moments of quiet introspection, little clearings in hectic unpredictable lives. Auntie Gulam, a transgender doyenne of the scene, is caught in shadowy hues of brown and orange against soft drapery, looking at the lens with eyes full of tender strength and questioning. Gulshan Khan’s photo-story on South Africa’s muslim community, particularly muslim women, leads us into a shy and secretive world, silent and huddled, lost in its devotion, more rarely seen by men than snow leopards. It requires a special skill to navigate your way into that world without upsetting people and draw such intimacy through your lens.

South Africa’s not seen and not heard are given the eye in Elijah Ndoumbe’s series Smoke Signals (A Quiet Song), a deep dive into the lives of Cape Town’s transgender and queer sex workers. The images avoid aggrandising, overblowing or pitying but rather capture fleeting moments of quiet introspection, little clearings in hectic unpredictable lives. Auntie Gulam, a transgender doyenne of the scene, is caught in shadowy hues of brown and orange against soft drapery, looking at the lens with eyes full of tender strength and questioning. Gulshan Khan’s photo-story on South Africa’s muslim community, particularly muslim women, leads us into a shy and secretive world, silent and huddled, lost in its devotion, more rarely seen by men than snow leopards. It requires a special skill to navigate your way into that world without upsetting people and draw such intimacy through your lens.

One of my Biennale highlights is David Uzochukwu’s Mare Nostrum, in which migrants are transformed into merfolk; no longer victims of the cruel sea but beautiful scaly and finned super-heroes of mysterious power and potential. His images have the deep-hued clarity and glow of a fashion shoot, but their beauty is far from skin-deep. They depict a ‘fantasy’ world that bears more truth than the one we see on our TV screens, because it honours the power of courage, hope, inner strength and resilience, that mainstream media footage never allows us to see.

Land becomes a metaphor for loss in the work of the photographers Hakim Benchekroun and Imane Djamil. The latter’s gorgeously immersive series 80 Miles To Atlantis depicts the southern desert city of Tarfaya which is situated on the coast opposite The Canary Islands, the purported location of Atlantis (pictured below). Tarfaya is slowly disappearing under the sand, a future myth in the making, but enough life remains to people Djamil’s images with small stick-like figures who are dwarfed by vast Saharan skies. You can almost hear their voices floating like bells in that immense silence. At dusk, the lunar landscape dissolves into a graduated glow of rose, yellow, gold, like a Rothko inspired by love rather than desperation. The series comes across as a hot and sandy counterpoint to Evgenia Arbugaeva arctic series Tiksi; both depict the dreamy face of a hostile environment that people somehow manage to call home. Benchekroun focusses on abandoned buildings and structures in his native Morocco that will soon disappear forever: a grand stairway in the desert that leads to thin air, a cluster of troglodyte caves, an ornate and ruined old church. They appear like bizarre mausolea, dead already but not quite forgotten thanks to Benchekroun’s inquisitive eye. Americo Hunguana from Mozambique presents a photo story about the old bull ring in the city of Lourenço Marques, where the world’s first black bullfighter Chibanga Ricardo made his name. The ring has been repurposed as an arcade of shops, stalls and garages, but the edifice is slowly crumbling to nothing.

In amongst the two-dimensional work are pieces printed on cloth, projected onto a pile of earth, compiled into a zine and exhibited as video and film. All of which attests to the Biennale’s boldly expansive answer to the question what is a photograph? The Biennale’s "Grand Prix" was awarded to the London-based British Ghanaian photographer and film-maker Baff Akoto for his film Leave The Edges, a dense, intensely lyrical composite of dance, poetry, music and moving image that traces lineages and explores chains that bind, chains that connect: the African origins of Flamenco, slave rebellions in Guadeloupe, black culture indelibly marked by colonialism and indelibly marking the coloniser (according to the catalogue). "I have a background a narrative drama director for TV and cinema, but I wanted to focus on other things here," Akoto says, "around cultural formation in different parts of the work, but ultimately tracing the lineage back to the African continent. And having the chance to do that with this project felt like a watershed moment for me."

Among other genre expanding contributions is the Senegalese Italian artist Adji Dieye’s 14 minute video titled Culture Lost and Learned by Heart, Memory. It shows Dieye playing a memory game consisting of small white ceramic squares with archival images from the iconographic collection of the National Archives of Senegal on their reverse side. Watching her hand turning over the squares, trying to match the images, was strangely mesmerising: I found myself yearning for pairings to appear, for history to be resolved and memory to be restored.

South African writer, artist and DJ Attiyah Khan is exhibiting a self produced zine title Bismillah that honours and explores her love of music from unbeaten paths, especially the Islamic countries of The Maghreb and Sahel. Printed on a risograph in black and red and so far distributed in minuscule quantities, the zine features images from album cover art, poems, Arabic calligraphy and other beautiful scraps. It’s a pocket-sized work of devotion to African sounds, cultures and beliefs, that earned Khan the Biennale’s Bisi Silva Prize, much to her immense surprise.

Khan added a whole other dimension to the project with a talk and DJ set at Bamako’s now defunct main railway station. Fans of Mali and Malian music will know that in its heyday, the station was a crucial hub for trade, connectivity and music, the terminus of a 1,287km line that linked Bamako and the Niger River to Dakar and the Atlantic coast. Both the line and the station were closed in 2018, after years of neglect and underinvestment. Now there’s talk of a renaissance: an accord has been signed with China for the complete renovation of the line as far as the Malian-Senegalese border, but work has yet to start. Meanwhile, the Biennale has taken it upon themselves to clean up the old terminal building, sweeping up piles of dirt and rubbish and giving the dilapidated walls a lick of paint to create a temporary exhibition space. "We really fought to have the railway station,’ says Bonaventure. ‘It’s such an important part of the city’s heritage, right next to the main market, in the centre of the city, a neighbourhood that couldn’t give a toss about ‘art’. But they come. I hope that others will see what we’ve done and continue the work."

Khan added a whole other dimension to the project with a talk and DJ set at Bamako’s now defunct main railway station. Fans of Mali and Malian music will know that in its heyday, the station was a crucial hub for trade, connectivity and music, the terminus of a 1,287km line that linked Bamako and the Niger River to Dakar and the Atlantic coast. Both the line and the station were closed in 2018, after years of neglect and underinvestment. Now there’s talk of a renaissance: an accord has been signed with China for the complete renovation of the line as far as the Malian-Senegalese border, but work has yet to start. Meanwhile, the Biennale has taken it upon themselves to clean up the old terminal building, sweeping up piles of dirt and rubbish and giving the dilapidated walls a lick of paint to create a temporary exhibition space. "We really fought to have the railway station,’ says Bonaventure. ‘It’s such an important part of the city’s heritage, right next to the main market, in the centre of the city, a neighbourhood that couldn’t give a toss about ‘art’. But they come. I hope that others will see what we’ve done and continue the work."

n the 1970s and 1980s, the Super Rail Band, one of the great names of modern Malian pop music, were employed by the national rail company to entertain travellers in the station’s buffet restaurant on a weekly basis, turning the place into a major landmark in the history of Malian music, as important in Malian terms as The Marquee in London, The Apollo in New York or The Cavern in Liverpool. Every night during inauguration week in December, the Biennale put on a concert outside the old station building, inviting revered names in Malian music–Afel Bocoum, Songhoy Blues, Madou Diabate–to bring back the sweet breath of music to this legendary venue. The highlight was a performance by the veteran Orchestra Badema, with guest appearances by ex-members of the Super Rail Band, all of them now in their 70s. The joy of the occasion ran deep, as did a sense of how fertile and generous Malian culture can be.

The battle to reach beyond the privileged art-loving bubble and persuade a wider demographic to venture inside is never easy. Doesn’t matter if you’re in Baltimore, Berlin or Bamako. In the decaying confines of the city’s Lycée for Young Girls, next to the main school building, one of the finest examples of 1930s West African Art Deco architecture in Bamako, there’s an annexe housing an exhibition that focusses on the dalits or "untouchables" of India. According to Bonaventure, the inclusion of Indian untouchables in a Biennale of African photography bears no contradiction: "All struggles are connected. Many people don’t know that when there were Black Panthers in the US, there were the Dalit Panthers in India who fought against the caste system, against racism and colonialism. I think it’s gift for those young girls and women to be in contact with that story of resilience."

When I visit the exhibition, a week after the opening, I find myself alone bar one other European couple who are pushing a pram with a small baby. The exhibition is diverse and thought-provoking, but the lack of people is dispiriting. The Biennale offers free-entry to all its exhibition spaces. It’s a generous, hard-won gift to Mali.

Outside in the hot noon-day sun, groups of girls come and go from their beautiful decaying school building, chatting away and occasionally throwing me curious looks and smiles. I have no idea what dalits mean to them, or the Biennale for that matters. But even if it’s just the barest presence of an another dimension, the shadow of a portal at the periphery of their vision that can lead them to other worlds, other viewpoints, other ways of thinking and being, even if they choose to ignore it altogether, then it’s a blessing, there for the taking. An invitation to escape the traffic, the violence, the sense of a world on the brink of meltdown and imagine another future.

![SEX MONEY RACE RELIGION [2016] by Gilbert and George. Installation shot of Gilbert & George 21ST CENTURY PICTURES Hayward Gallery](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_125_x_125_/public/mastimages/Gilbert%20%26%20George_%2021ST%20CENTURY%20PICTURES.%20SEX%20MONEY%20RACE%20RELIGION%20%5B2016%5D.%20Photo_%20Mark%20Blower.%20Courtesy%20of%20the%20Gilbert%20%26%20George%20and%20the%20Hayward%20Gallery._0.jpg?itok=3oW-Y84i)

Add comment