Ex-voto paintings are a tradition in Mexico, an offering of gratitude to God and the saints for answered prayers, row after row of them lining the walls of Mexican churches, testifying to the congregations’ devotion, and to the enduring link between man and the spiritual. In artistic terms, however, these paintings, which have been created from the 16th century onwards, are one of the great national archives of folk art, extraordinary depictions of ordinary people: a moving, comic, tragic, epic narrative that is not to be missed.

Ex-votos, or retablos, began to be painted in the 16th century, and by the 19th century they were perhaps the most democratic form of art ever known: painted on tin roof tiles, the painters charging modest sums, in this format almost everyone can commission art. The Wellcome’s exhibition, Infinitas Gracias, is a glorious baroque display, showing a tiny proportion of the riches that lurk in every church.

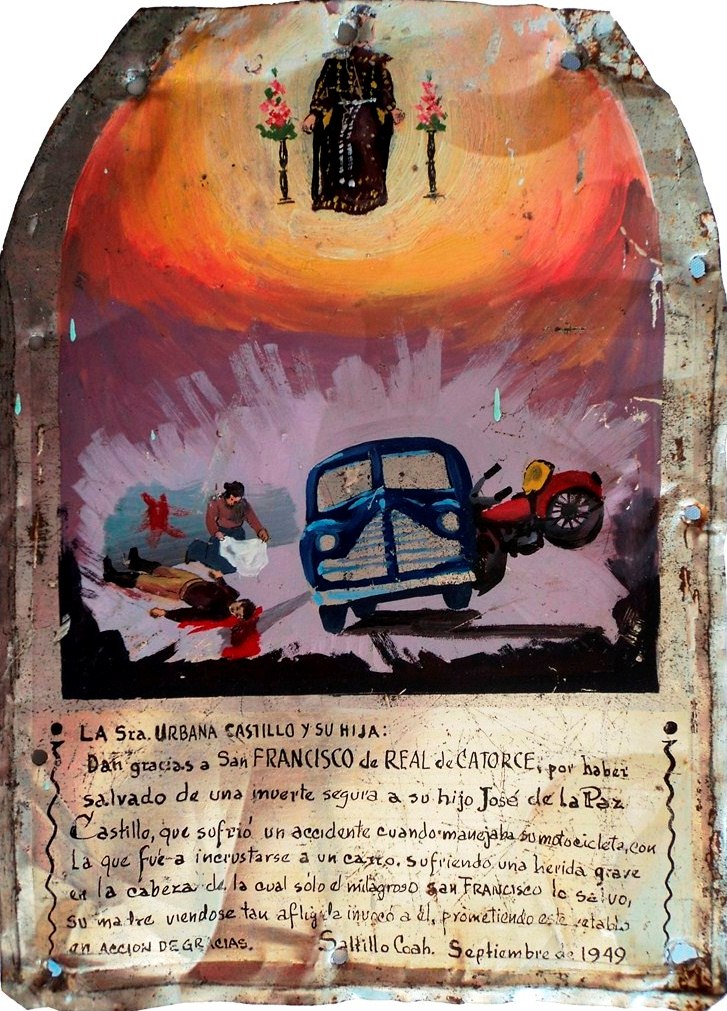

Disasters and death, accidents and disease abound. Thanks are given for a woman who miscarries after having been infected with smallpox in one of the earliest retablos, dating from 1748: here an austere couple kneel before the saint who is to relieve them, while, in a lovely surreal touch, some musicians perform behind a screen. Smallpox is the least of it, however, and other disasters include falls, children kicked by horses, car crashes (pictured right, from Santuario de San Francisco de Asis de la Diócesis de Matehuala/INAH), kidnappers, madness, storms, scorpions, runaway bulls (pictured below, Museo Nacional de Historia/INAH) mugging and more. Life is bleak and dangerous, yet these tiny iterations of faith remain serenely, sublimely confident that there is meaning after all.

Disasters and death, accidents and disease abound. Thanks are given for a woman who miscarries after having been infected with smallpox in one of the earliest retablos, dating from 1748: here an austere couple kneel before the saint who is to relieve them, while, in a lovely surreal touch, some musicians perform behind a screen. Smallpox is the least of it, however, and other disasters include falls, children kicked by horses, car crashes (pictured right, from Santuario de San Francisco de Asis de la Diócesis de Matehuala/INAH), kidnappers, madness, storms, scorpions, runaway bulls (pictured below, Museo Nacional de Historia/INAH) mugging and more. Life is bleak and dangerous, yet these tiny iterations of faith remain serenely, sublimely confident that there is meaning after all.

Many of the works are charming. Others are powerful. More than a few have clearly powerfully influenced artists from Frida Kahlo to Francis Alÿs. One, with its inscription missing, shows a yellow floor, two giant wooden chairs and a bed on which stands a tiny peasant woman. What is the miracle that has been performed? One has no more sense than in a Max Ernst vision, and yet the picture continues to resonate.

In the second room the curators have recreated an ex-voto wall from the church of Cristo de Villaseca, where the Cristo Negro hangs above the altar, performing miracles in the old silver-mining town of Guanajuato. Here are letters, cards, photographs, crocheted baby clothes, a wedding dress, even a drawing on a Styrofoam fast-food tray, all left by petitioners who ask the Señor de Villaseca to help them. Here are also three short films, one showing a retablo being commissioned, as the supplicant tells the artist his story, which is then fleshed out in front of him, his communication with the saints made visible; another is an interview with a man caught in an earthquake, who helped rescue others trapped in the rubble: he commissions a retablo which is erected in a small niche in the rebuilt street: for those who are here, he says, for those who should be here, and for those who are here no longer.

Another silver town, now mostly denuded of its population, holds a week-long fiesta in honour of their patron saint, St Francis of Assisi. Here are not only retablos, but also "milagritos", little miracles, small amulets and charms left in the church to ask for a blessing or a cure. These are then made into decorative panels by the church, or sewn onto the robes worn by the image of St Francis that is paraded through the town.

Another silver town, now mostly denuded of its population, holds a week-long fiesta in honour of their patron saint, St Francis of Assisi. Here are not only retablos, but also "milagritos", little miracles, small amulets and charms left in the church to ask for a blessing or a cure. These are then made into decorative panels by the church, or sewn onto the robes worn by the image of St Francis that is paraded through the town.

These small charms frequently represent a body part – an arm, a leg, an eye – and in the Wellcome’s parallel exhibition, Charmed Life, drawing on the collection of folkloric amulets and charms put together by Edward Lovett (1852-1933) and given to the Pitt Rivers Museum in Oxford (pictured below). Lovett was an amateur, a cashier at the Bank of Scotland in the City, who nonetheless saw himself as a "seeker after amulets". For this, he wrote, "There is no better hunting ground than the hawker’s handbarrow in the poorest parts of slums of such dense aggregations of people as London, Rome, and Naples... For many years I have been in touch with some of the London street dealers in unconsidered trifles."

Some amulets remain a mystery today – a piece of folded bark may be in one of Central America’s indigenous languages, and may date from the seventh century, but it is too fragile to be unfolded, and will remain forever a mystery. Others have a careful provenance – the British Museum has loaned its "touchpiece" owned by Dr Johnson, which was used to cure him of scrofula as a child.

Some amulets remain a mystery today – a piece of folded bark may be in one of Central America’s indigenous languages, and may date from the seventh century, but it is too fragile to be unfolded, and will remain forever a mystery. Others have a careful provenance – the British Museum has loaned its "touchpiece" owned by Dr Johnson, which was used to cure him of scrofula as a child.

But most of the pieces have no history, and remain as autonomously mysterious as their quondam owners. The Wellcome invited artist Felicity Powell to make a selection and display from the Pitt Rivers collection, and as well as showing some of her own pieces, based on her response to the collection, through the room runs a river of amulets, of punched tin, glass, bone, coral and metal depicting figures, faces, animals, hearts, eyes, hands, fish, seahorses, shoes, teeth, acorns, horseshoes, skulls and more. There is a vertebrae (I think) with a skull carved out of it. There is a pair of pigeons, the size of a pinkie nail, from Japan. Five dice that make the pigeons look like giants. There is no purpose, as there could not be, to the collection, but the detail is enticing, the overview serene.

The faith, the belief that motivated people to make these charms, and then to carry them, is no different to the faith that created the retablos next door. Those, based on Catholic faith, we still comprehend; the charms, based on almost lost folk traditions, less so. Both are beautiful, and the Wellcome has curated, especially with the retablos, what may just be the sleeper show of the season.

- Miracles and Charms at the Wellcome Collection until 26 February, 2012

Watch the exhibition trailer

Add comment