Here be wonderful images, in an anthology of two score of paintings and drawings from the 1950s through the mid-Nineties by 10 artists whose shared interests only sharpen their individuality. Francis Bacon is the autodidact in the group, which includes two Berliners – Frank Auerbach and Lucian Freud – who came to England as children. David Hockney is the witty, adventurous northerner who has now returned, mostly, to Yorkshire from a life lived between London and Los Angeles. Patrick Caulfield is primarily concerned with vibrant still lifes and domestic interiors, Euan Uglow and William Coldstream with the human model, Leon Kossoff with cityscape and model. Richard Hamilton is the most overtly political and Michael Andrews perhaps the most unclassifiable. The common thread is their preoccupation with the observed rather than the imagined world, and their obsession with painting.

This extraordinary compilation is subtitled "Conversations between 10 British postwar painters". Other members of this very loose network could have been included, but the tightness of the definition makes for a sharply focused show. Several of them work obsessively from the life model, or in front of the motif. Some use photography and others use illustrative skills to collage together elements from the external world. No work is devoid of people – or at the very least, the city – and human artefact: the domestic still life.

The title comes from aphoristic remarks by Francis Bacon, worth repeating: "To me, the mystery of painting today is how can appearance be made. I know it can be illustrated, I know it can be photographed. But how can this thing be made so that you catch the mystery of appearance within the mystery of the making?"

The title comes from aphoristic remarks by Francis Bacon, worth repeating: "To me, the mystery of painting today is how can appearance be made. I know it can be illustrated, I know it can be photographed. But how can this thing be made so that you catch the mystery of appearance within the mystery of the making?"

The exhibition is really about the mystery of appearances, in the plural, for nobody sees alike. The common denominator is not just an almost obsessive interest in that subject, but also an exceptionally informed art historical knowledge. These artists have copied in the galleries (to copy, to create, as a huge exhibition in the Louvre once put it) and from, in the case of Francis Bacon, photographs: he had a famously problematic relationship with original works of art by Old Masters, not wishing to see the originals. Although the works on view demonstrate fascinating differences as well as shared traits, the thrust of the argument is the myriad layered visual conversations between the protagonists.

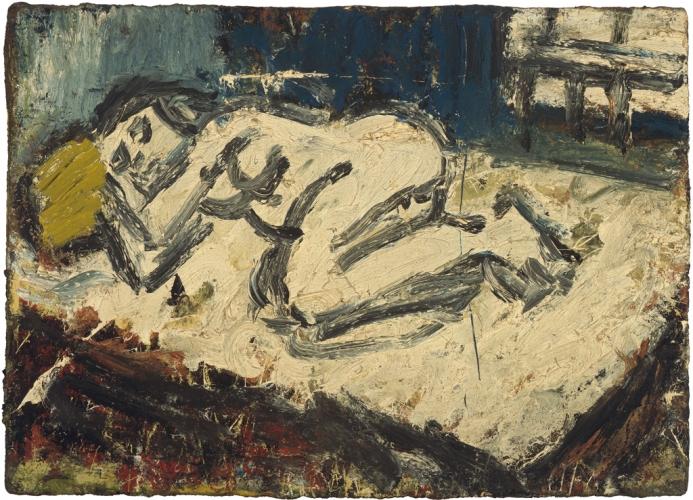

We are introduced first through a sharp selection of portraits, from models and friends. Frank Auerbach’s Reclining Figure, 1972, is a cascade of yellow, pink and white oblongs, abstract and yet utterly, alarmingly convincing as a study from the model. The sharp, tingling colour is set against a sombre background, the paint almost crusted. Leon Kossoff’s Nude (Autumn Morning), 1971 (see main image), is his characteristic concatenation of blacks and greys, thickly painted, from which the figure convincingly emerges; now you see her, now you don’t. These bold outlines and sober colours do somehow magically describe human flesh. Lucian Freud gives us Lady Anne Tree, circa 1950, an incandescent study of a woman’s face, her eyes half closed, looking down. Her pose is ineffably demure, almost elusive: a disguise, perhaps, a meditation on the impossibility of knowing another person. And here too is Freud’s tiny miniature of a wilfully distorted Girl on a Turkish Sofa, with a huge bottom and huge feet thrust towards us, so oddly vital and perverse.

There are complex, deadpan, painfully measured seated nudes by Coldstream and Uglow which feel almost life size. Their seated naked women are also surprisingly tactile, rosy-tipped breasts caressed by the painter’s eye, but the effect is calm, serene and statuesque.

Old Mastery redone abounds: A Woman Bathing after Rembrandt by Kossoff, a screaming Pope I - Study after Pope Innocent X by Velazquez, 1951 (pictured above right) by Bacon, an almost lighthearted partial and tiny version of The Massacre of the Innocents by Uglow.

There are splendid cityscapes: two vibrant Auerbachs, Primrose Hill, Winter Sunshine, 1962-64, aglow with that curiously alluring half light of dark days, and Study of Primrose Hill, 1973-74 (pictured above) – one of the subjects of which he never lets go – flank an almost identically sized Kossoff city tangle, Willesden Junction, Summer No 1, 1966.

There are splendid cityscapes: two vibrant Auerbachs, Primrose Hill, Winter Sunshine, 1962-64, aglow with that curiously alluring half light of dark days, and Study of Primrose Hill, 1973-74 (pictured above) – one of the subjects of which he never lets go – flank an almost identically sized Kossoff city tangle, Willesden Junction, Summer No 1, 1966.

The revelation for many may well be the intense beauty and interest of two magnificent, memorable large paintings by Michael Andrews, perhaps even now the least known of the 10. Andrews always painted on and about the human condition, even in his series of Australian landscapes of views of Ayers Rock (Uluru).

His The Lord Mayor’s Reception in Norwich Castle Keep, 1966-69 (pictured left), represents an astonishing and vivid social gathering of East Anglian grandees grouped in all kinds of formations and permutations of social chitter chatter and connection. A tiny line of waitresses stand to one side ready to move in, flanked on the other by a groaning buffet table.

His The Lord Mayor’s Reception in Norwich Castle Keep, 1966-69 (pictured left), represents an astonishing and vivid social gathering of East Anglian grandees grouped in all kinds of formations and permutations of social chitter chatter and connection. A tiny line of waitresses stand to one side ready to move in, flanked on the other by a groaning buffet table.

It's an utterly modern version of the conversation piece. Andrews was a master of the social painting on all levels, more louche occasions being the subjects of All Night Long and Good and Bad at Games, memorable masterpieces in public collections. Near the end of his life he painted a series of marvellously contemplative paintings of the Thames estuary, represented here by The Thames at Low Tide, 1994-95: two empty rowboats seen from slightly above, beached by the river which is flowing in misty clouds of grey, taking an unseen cargo who knows where. It is surely one of the most beautifully elegiac paintings of the modern period, and it is heartbreaking.

![SEX MONEY RACE RELIGION [2016] by Gilbert and George. Installation shot of Gilbert & George 21ST CENTURY PICTURES Hayward Gallery](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_125_x_125_/public/mastimages/Gilbert%20%26%20George_%2021ST%20CENTURY%20PICTURES.%20SEX%20MONEY%20RACE%20RELIGION%20%5B2016%5D.%20Photo_%20Mark%20Blower.%20Courtesy%20of%20the%20Gilbert%20%26%20George%20and%20the%20Hayward%20Gallery._0.jpg?itok=3oW-Y84i)

Add comment