It might be said that Paula Rego’s subject is light: but rather than painting it, she gives it. She paints deep into social corners, affording generous and often unnerving representation to worlds forgotten or forced out of sight. This isn’t always a comfortable experience, and her figures are frequently refracted or distorted, bent out of shape in a desperate need to be seen. They are, in many ways, acts of resistance. Take, for instance, her suite Dog Woman, 1994, which depicts a series of women bestially poised: crouched and self-grooming, cornered, supine and submissively wide-eyed, or else sitting dutifully for Master. As with much of Rego’s work, the simple satire bites hard.

The same relentless focus can now be found in The Forgotten, a recollection of Rego’s work from the past 20 years which fills in some of the blanks left by the recent Tate Britain retrospective, with the former featuring works painted post-2009 (the end of the Tate show’s remit). But The Forgotten is more than a coda. For a start, it occupies the whole of Islington’s Victoria Miro gallery, making deft use of the gallery’s jarring architecture, its semi-hidden stairways, shadow-rich niches, and industrial resonance. It offers a place in which to step, with unsure tread, around Rego’s labyrinthine mind, with her recurrent themes – mental illness, familial discord, sexual and social violence – masterfully displayed and, as ever, difficult to look at. This is Rego’s art: to painfully – and sometimes tenderly – foreground those facts we prefer to keep at arm's length.

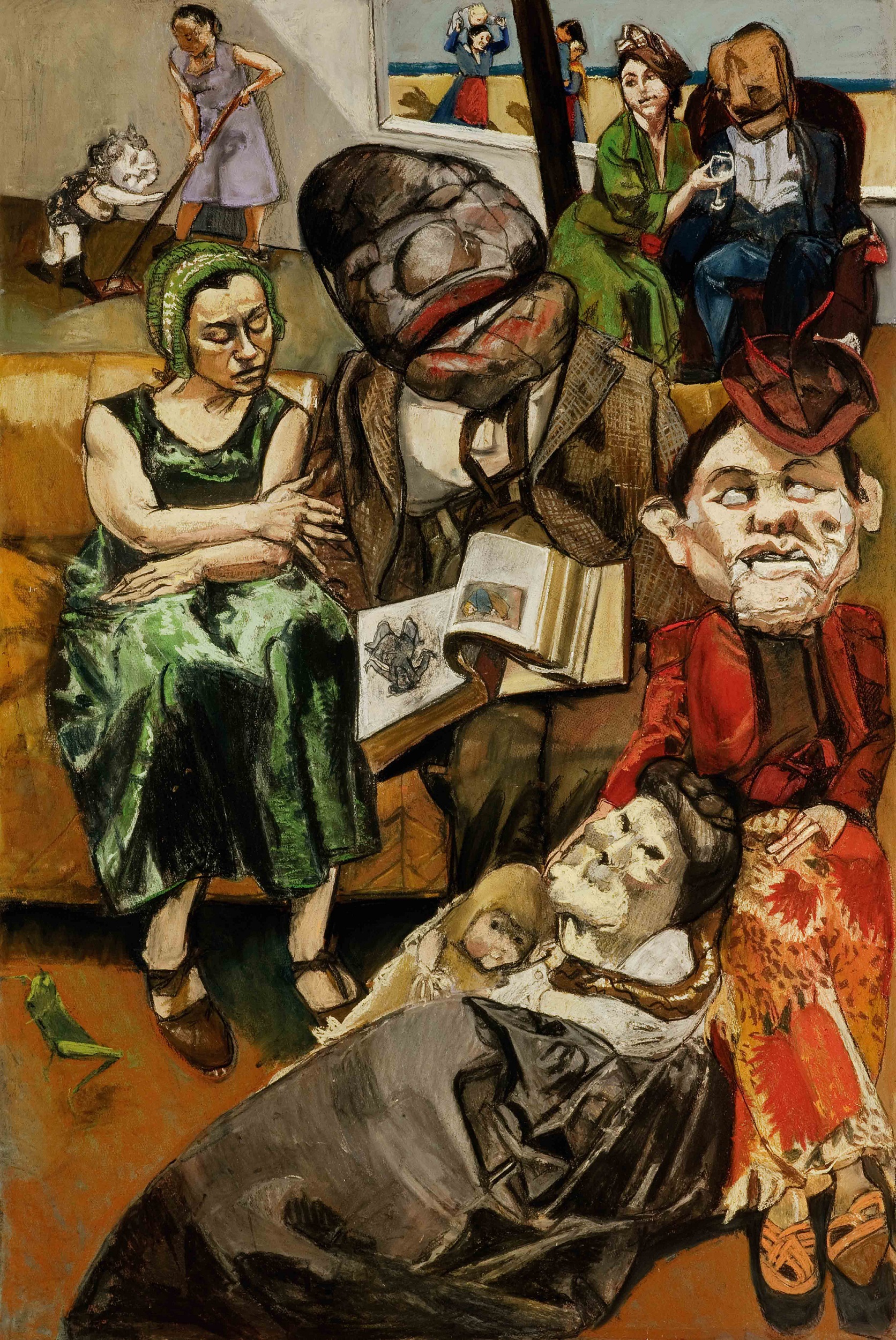

On entering the gallery (through an easy-to-miss door), we encounter three large and daunting portraits drawn from memories of Rego’s childhood. They depict – as well as fishing trips and readings of Dante’s Commedia – a tale of folie en famille, scenes of her father’s depression that Rego considers her inheritance (pictured right: Reading the Divine Comedy by Dante, 2005). Both father and mother veer away from human form, appearing hauntingly puppet-like – oversized dolls awkwardly posed in a weird inversion of childishness. But, in the central painting entitled La Marafona, 2005 (pictured below left), the eye might be equally drawn to the father’s feet, as much as the lolling doll’s head. They arch uncannily, toes curled – perhaps wracked with cramp like Rodin’s Mains crispée gauche – as though simply being held in frame is a painful extremity. Here Rego surreally pictures not only the difficulty of looking, but the pressure of being seen. The family is glaringly unsure of how to appear, though Rego’s head resting on her father’s arm provides a careworn sense of understanding.

On entering the gallery (through an easy-to-miss door), we encounter three large and daunting portraits drawn from memories of Rego’s childhood. They depict – as well as fishing trips and readings of Dante’s Commedia – a tale of folie en famille, scenes of her father’s depression that Rego considers her inheritance (pictured right: Reading the Divine Comedy by Dante, 2005). Both father and mother veer away from human form, appearing hauntingly puppet-like – oversized dolls awkwardly posed in a weird inversion of childishness. But, in the central painting entitled La Marafona, 2005 (pictured below left), the eye might be equally drawn to the father’s feet, as much as the lolling doll’s head. They arch uncannily, toes curled – perhaps wracked with cramp like Rodin’s Mains crispée gauche – as though simply being held in frame is a painful extremity. Here Rego surreally pictures not only the difficulty of looking, but the pressure of being seen. The family is glaringly unsure of how to appear, though Rego’s head resting on her father’s arm provides a careworn sense of understanding.

The floor directly above houses paintings of a similar subject, but under a crucially different aspect. Depression Series, 2007, is less surreal, less darkly comic, and perhaps therefore more simply moving. They are portraits by a gentler hand. Each painting, compared to the works positioned now under your feet, is disturbingly muted, displaying – almost invariably – the figure (sitting, prone, or supine) soundlessly struggling to get up in blunt streaks of lightly-then-heavily daubed pastel. Overpainting these scenes of deepest inertia with further tragic force is their history: Rego kept them from public view (locked in a drawer) for ten years, feeling – in her word from a video made to accompany the exhibition – "ashamed" of what they show.

Having walked through the gallery’s garden and up a second set of stairs to Gallery 2, the viewer – perhaps a little breathless – will encounter another perspective-shift. On this more brightly lit floor is 2001’s Misericordia (main picture): frames crowded with disparate bodies, comforting and embracing each other, or else merely staring. They reveal old age in all its discomforts (specifically they show Rego’s mother in failing health), as well as delicately detailing the loving sadness felt at a life’s end. To the right hang a suite of self-portraits which might be, at first glance, the most unassuming pieces in the exhibition. Made in 2017 after Rego had suffered a fall and damaged her face, they become fraught mirrors: the mouth, variously distorted, howls silently or grits its teeth; her body, in one instance, is reduced to a fading line; the face, Bacon-like, is shocked by its own reflection.

But it is the gaps in these self-seeings, their fallings-away and self-erasures that constitute her most revealing work. Rego’s reality is total, so it comprises social embarrassment, stigma, and taboo; but also blankness and lacunae, remorselessly re-encountering those moments of doubt and absence that make up a complete person. Because of this, truly seeing yourself is one of life’s most difficult revelations, but within Rego’s generous art, we can catch the briefest glimpse of it.

Add comment