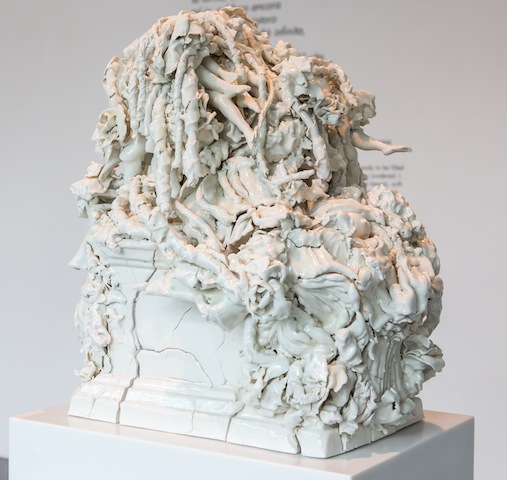

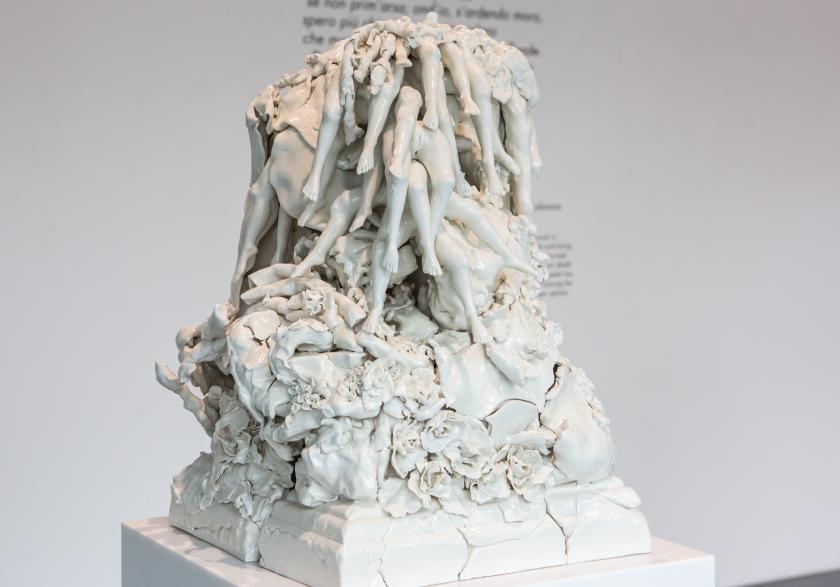

In an oft quoted moment of self-deprecation, WH Auden once described his own face as looking like “a wedding cake left out in the rain”. But the poet might have thought twice if confronted with the Porcelain confections of Rachel Kneebone. The London-based artist has brought three of her sculptures to the gallery of the University of Brighton; each one piles flora, vines and body parts onto a tomb-like plinth. They are as grand as wedding cakes, sugar white, and slick with a wet-looking glaze.

Look closer and delicate flowers dissolve into less seemly clumps of undergrowth. Tendrils look like entrails one moment, the next like spines, or like rope binding the whole production in place. And, as if freshly exhumed, slender female legs emerge before your eyes. In a poignant touch, you can make out toenails. Here and there you find a crack in the base or a gap in the thicket, through which you glimpse a hollow interior, as if the towering array might at any moment collapse.

The perfect legs bring to mind a dismembered Barbie. Elsewhere the creepy female torsos of Hans Bellmer are recalled. White orb-like belly and butchered joints nestle amid the confusion, ready to increase your sense of horror. Like Bellmer in the 1930s, Kneebone might well have found favour with the Surrealists. Her work is certainly dark and dream-like.

Today, it is hard to guess at Kneebone’s peers. A recent survey of figurative sculpture at the Hayward Gallery (The Human Factor) revealed nothing quite like her effusive vision. Perhaps the bulbous clay sculptures of Rebecca Warren share a sense of bodily excess. That show confirmed that the human form has, for decades now, been back in business. And once again we have a sculptural landscape which reflects a classical tradition.

Poetry is the best way in here. Kneebone present two sonnets by Michelangelo, which can be read on the wall. These evoke the romance of the workshop, and the use of fire and mould, both of which this contemporary sculptor must use to bring her creations to life. But parallels between the Renaissance master and his modern admirer should end there. There is nothing Apollonian about Kneebone’s vision. If Michelangelo’s most famous slave enjoys a dignified death, Kneebone’s carnage of female parts call to mind a mass grave.

Poetry is the best way in here. Kneebone present two sonnets by Michelangelo, which can be read on the wall. These evoke the romance of the workshop, and the use of fire and mould, both of which this contemporary sculptor must use to bring her creations to life. But parallels between the Renaissance master and his modern admirer should end there. There is nothing Apollonian about Kneebone’s vision. If Michelangelo’s most famous slave enjoys a dignified death, Kneebone’s carnage of female parts call to mind a mass grave.

It was Theodor Adorno who said “To write poetry after Auschwitz is barbaric”. But even though conjuring the worst moments of human history, Kneebone’s show remains defiantly lyrical. As Ali Smith, curator of this year’s Brighton Festival, has said: “Gravity meets lightness, graveness meets delight.” What looks at first good enough to eat, reveals itself to be more like a landslide in an untended cemetery. If we dine, we do so amid the ruins. If we mourn, we don’t know where to begin.

![SEX MONEY RACE RELIGION [2016] by Gilbert and George. Installation shot of Gilbert & George 21ST CENTURY PICTURES Hayward Gallery](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_125_x_125_/public/mastimages/Gilbert%20%26%20George_%2021ST%20CENTURY%20PICTURES.%20SEX%20MONEY%20RACE%20RELIGION%20%5B2016%5D.%20Photo_%20Mark%20Blower.%20Courtesy%20of%20the%20Gilbert%20%26%20George%20and%20the%20Hayward%20Gallery._0.jpg?itok=3oW-Y84i)

Add comment