England is in the throes of an unusual Teutonic love fest, and in 2014 no doubt deliberately. Music of course has always been omnipresent: Bach to Wagner, and a passion for Beethoven and Schubert that knows no bounds. But there has been a love-hate relationship with the visual arts. We are somewhat uncomfortable with the Northern Renaissance, preferring the Italian, and as for expressionism, that was, for a long time, far too blatantly emotionally strident and in your face. There was a moment in the 19th century when artists fell for the Nazarenes, but that helped to lead to the Pre-Raphaelites and we all know they were out of favour for a century or so.

London though is now stoking the fires very nicely, partly in a stupendous attempt to understand that very tricky and contradictory history from those native German speakers, from leading the Reformation and the Enlightenment to the unspeakable horrors of the last century. An exhibition simply and audaciously called Germany opens next week at the British Museum, and, complementing that, the leaders of the art market have piled in. We've already had Georg Baselitz, now Anselm Kiefer is at the Royal Academy, Gerhard Richter is still to come at Marian Goodman, and, just opened, the perverse blockbuster and the first full retrospective of the most difficult, irreverent and maverick late 20th-century German artist of them all, Sigmar Polke (1941-2010).

Polke was born in what is now Poland, and brought up in East Germany, before the family got to West Germany when Polke was 12. As a young artist anything and everything could and was used as he floated, on gigantic canvases, figurative elements against elaborate geometric patterns. He mixed abstraction and figuration, threw in sources from 19th-century engravings to advertising to beguilingly messy imitations of those dots that make up newsprint imagery. Moreover he was multi media – using film, sculpture and photography, even deploying photocopying and other devices, and mixing up techniques of reproduction with the handmade. And he was “multi mixture” too, using all kinds of chemical substances, radioactive material, resins, lacquers, lead, silver, enamel, gold, and objects. The huge canvas The Spirits that Lend Strength are Invisible, has tiny Neolithic shards cascading across the surface.

The Tate tells us with a wonderfully straight face, that Polke had an eccentric lifestyle and experimented enthusiastically with hallucinogenic substances and that – therefore? – mushrooms featured in many a work. Here is Polke’s enormous homage to Alice in Wonderland, complete with mushroom, of course, not to mention Alice and the Caterpillar, smoking his hookah. It's executed in Polke’s usual mad mixture of acrylic, poster paint, spray paint, metallic paint, all on varieties of patterned fabric, including two panels with tiny figures playing basketball and a big outlined figure of a basketball player to add to the general hub bub. Was Alice on drugs? She certainly nibbled on mushrooms to grow bigger and smaller, and Polke too was interested in hallucinogenic substances. Set against this slightly manic tableau are columns of the manipulated photographs Polke took of mushrooms.

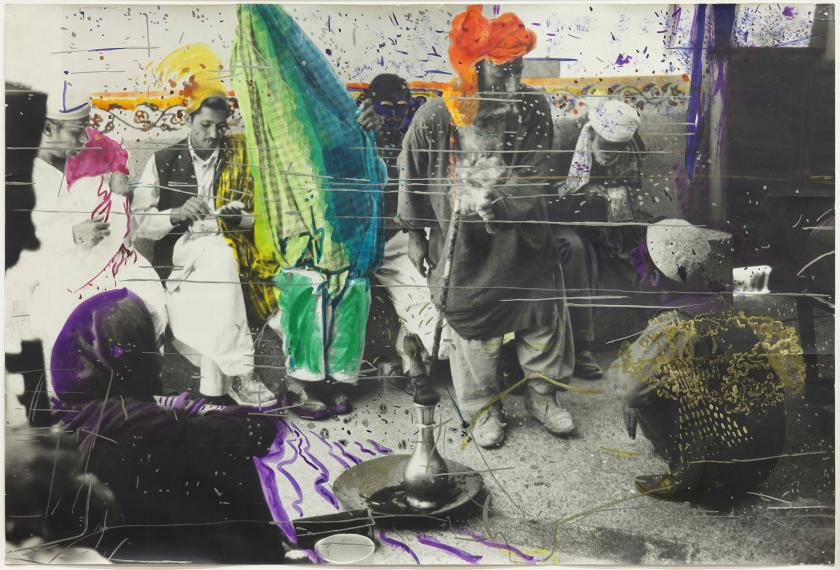

Like Richter, Polke was a student at the Kunstakademie in Düsseldorf, home of course to Professor Joseph Beuys, and to the Düsseldorf school of photography, so influential now for half a century. With Richter – nine years older – and others, Polke invented a kind of anti-Pop Pop art, calling it Capitalist Realism; tongue in cheek they said only great people could paint and they had to take matters into their own hands – they could not simply depend on good paintings being made one day. But Polke's own path swerved and turned. He lived in an artists’ commune, he travelled from Brazil to Afghanistan, and mixed professional skill with deliberately clumsiness – it took a lot of skill to be at times so clunky. He overlaid photographs of opium dens in Pakistan (see main picture) with layers of paint; he giggled helplessly in a film he made while reading a 17th-century tract; he obsessed with palm trees as a motif; he made a wood and wire lattice shed and studded it with potatoes; he posed for a series of photographs lying on an elaborate oriental carpet wrapped up – in various ways – in an awesome python skin.

Like Richter, Polke was a student at the Kunstakademie in Düsseldorf, home of course to Professor Joseph Beuys, and to the Düsseldorf school of photography, so influential now for half a century. With Richter – nine years older – and others, Polke invented a kind of anti-Pop Pop art, calling it Capitalist Realism; tongue in cheek they said only great people could paint and they had to take matters into their own hands – they could not simply depend on good paintings being made one day. But Polke's own path swerved and turned. He lived in an artists’ commune, he travelled from Brazil to Afghanistan, and mixed professional skill with deliberately clumsiness – it took a lot of skill to be at times so clunky. He overlaid photographs of opium dens in Pakistan (see main picture) with layers of paint; he giggled helplessly in a film he made while reading a 17th-century tract; he obsessed with palm trees as a motif; he made a wood and wire lattice shed and studded it with potatoes; he posed for a series of photographs lying on an elaborate oriental carpet wrapped up – in various ways – in an awesome python skin.

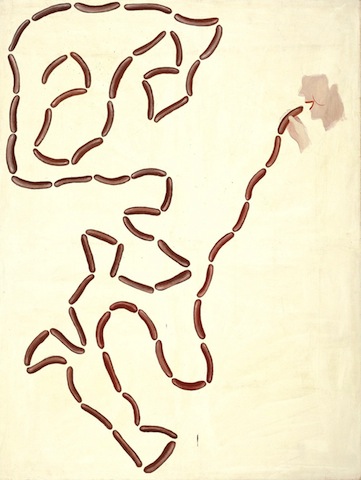

In his earliest works he addressed consumerism, advertising, human appetite, misplaced ambition. A relatively conventional painting, Polke’s Collected Works, depicts a row of 17 books in brown bindings with gilt titles; he painted cream biscuits with fidelity, and a man poised to eat a swirling line of linked sausages (pictured above right: The Sausage Eater, 1963). Careful scrutiny of that early painting reveals a loose configuration of a map of Europe, so putting a pungently political spin on a work that appears at first simply playful and lighthearted – Polke was always interested in the way things were revealed or transformed to the viewer when looked at over time, or from a different angle.

In a gallery called Modern Art, after an exhibition Polke held in 1968, there are a host of paintings in which Polke gently parodies the languages of abstraction. Stripe Painting is, well, four stripes. In Solutions he carefully painted numerical sequences where nothing adds up. Eightlines, too, is just that, and Constructivism mocks Mondrian among others. This host of paintings has a curious flavour: a sense of enjoyment, even affection as Polke turned the seriousness of the isms he satirised into a kind of childish frivolity, and showed he knew his stuff well enough to throw it all away. The Large Cloth of Abuse is a flannel on which Polke just wrote lots of single word insults, of which "idiot" is one of the most polite; and in ballpoint and pen he depicted a Malevich Looks Down on Pollock.

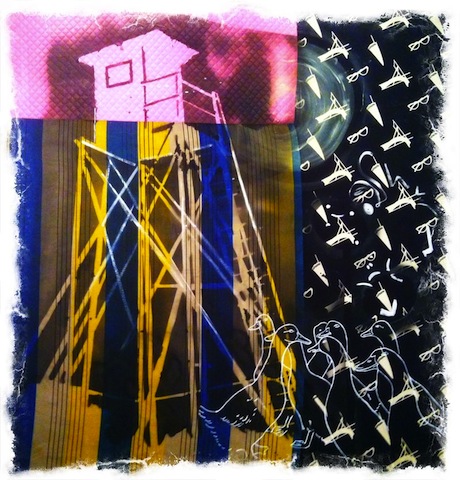

He continually questioned authority and, of course, delved into the National Socialism of his own country’s recent history. For his appearance at the 1986 Venice Biennale in the German pavilion, an irritatingly demure building in National Socialist style, he put up his painting Policeman and Pig and painted the outside with chemical substances that altered with light. The Watchtower paintings of the 1980s (pictured left: Watchtower with Geese, 1987-88) show those huge structures that are found on national borders, and which, of course, surrounded concentration camps, but are also in more modest form seen throughout the German countryside, and used by hunters. In several, the chemicals he used cause the paintings to naturally darken. The images are somehow terrifying, grand and implacable, symbols of who knows what authority: spying, destroying, keeping people safe, or just rural diversions? And he could make something too that was so unexpectedly beautiful, painting with soot on huge glass panels in1990 in a work simply called Untitled. Polke could exploit accident to purposeful and beguiling effect, seeking a transformation as alchemists have throughout history.

He continually questioned authority and, of course, delved into the National Socialism of his own country’s recent history. For his appearance at the 1986 Venice Biennale in the German pavilion, an irritatingly demure building in National Socialist style, he put up his painting Policeman and Pig and painted the outside with chemical substances that altered with light. The Watchtower paintings of the 1980s (pictured left: Watchtower with Geese, 1987-88) show those huge structures that are found on national borders, and which, of course, surrounded concentration camps, but are also in more modest form seen throughout the German countryside, and used by hunters. In several, the chemicals he used cause the paintings to naturally darken. The images are somehow terrifying, grand and implacable, symbols of who knows what authority: spying, destroying, keeping people safe, or just rural diversions? And he could make something too that was so unexpectedly beautiful, painting with soot on huge glass panels in1990 in a work simply called Untitled. Polke could exploit accident to purposeful and beguiling effect, seeking a transformation as alchemists have throughout history.

Add comment