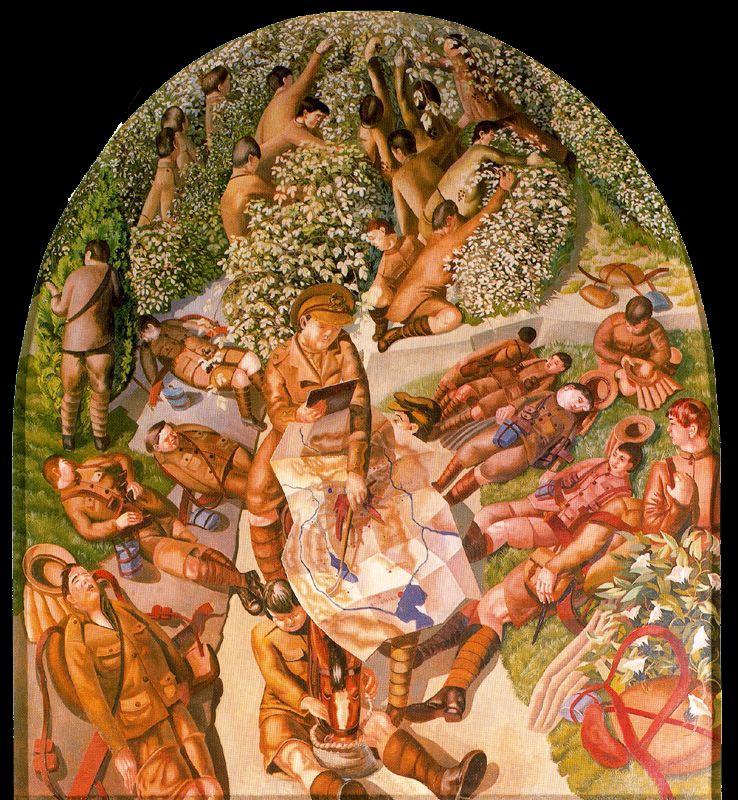

Stanley Spencer’s painting Map Reading shows us, in dizzying perspectives and changes of scale, a mounted cavalry officer reading a huge unfurled map concerning the now forgotten campaign in Macedonia in World War I, his horse nibbling oats all the while. Clustered all around his giant figure, ordinary soldiers surround their commander, fanned out at oblique angles to his central figure. The men are lying about in various casual poses, resting, or are perhaps out of this world, in more ways than one. The whole is framed by gorgeous outbursts of white blossom. The military uniforms, hats and heavy boots are extraordinary varied browns, the grass is green and the obligatory water-bottles in each man’s kit a surprising blue.

Somerset House provides an unrepeatable experience, as we are able to see the newly restored paintings close up in bright light

Map Reading (pictured below) is but one of the commemorative 16 paintings – lunettes and predellas – which are visiting London while their normal home, the modest (but listed Grade I) red brick 1920s Sandham Memorial Chapel in Burghclere, Hampshire, now in the care of the National Trust, is conserved and restored. Three wall murals including the Resurrection, here in a major back-lit reproduction, could not be moved for this unprecedented visit to London, an exhibition Stanley Spencer (1891-1959) had passionately wished for. He knew their quality, because of his own extraordinary view of life which combined confidence and diffidence, naiveté and sophistication.

The paintings were inspired by Spencer’s own war experience, and were six years in the making (1926-1932). They were modelled in some ways on Giotto’s early 14th-century Arena Chapel in Padua in terms of their three-tier stacking. They have Spencer’s highly unusual combination of the spiritual and the earthly, the imaginative and the real, and the quotidian and the miraculous; in that sense they also very subtly echo the ethos of Giotto’s extraordinary introduction of the realistic and the believable into the miraculous.

The paintings were inspired by Spencer’s own war experience, and were six years in the making (1926-1932). They were modelled in some ways on Giotto’s early 14th-century Arena Chapel in Padua in terms of their three-tier stacking. They have Spencer’s highly unusual combination of the spiritual and the earthly, the imaginative and the real, and the quotidian and the miraculous; in that sense they also very subtly echo the ethos of Giotto’s extraordinary introduction of the realistic and the believable into the miraculous.

The scenes are partly set in Macedonia, the campaign in which Spencer took part, and in the Beaufort War Hospital, Bristol, where he also served. In Ablutions (main picture) there is almost a sense of the wounded saint, as the sturdy half-naked solider has iodine painted on his chest wounds, while elsewhere muscled men wash themselves aided by male and female nurses in the communal hospital bathroom.

Convoy Arriving with the Wounded is just that, an open lorry carrying the helmeted soldiers, each of whom has an arm in a shining white sling, the lorry improbably surrounded by rhododendron blossom; two enormous men, one with a cluster of keys at his waist, open high iron gates to let the lorry through into the hospital. Other hospital scenes show orderlies sorting out fat padlocked black kit-bags in grim prison-like surroundings – the hospital treated both the war-wounded and the shell-shocked. Scrubbing the Floor has as its focus a shell-shoked solder prostrate in a corridor, obviously ritualistically washing the same area of dirty floor. Above this abject figure a trio of bustling workers, oblivious to his plight, carry trays of bread for the patients.

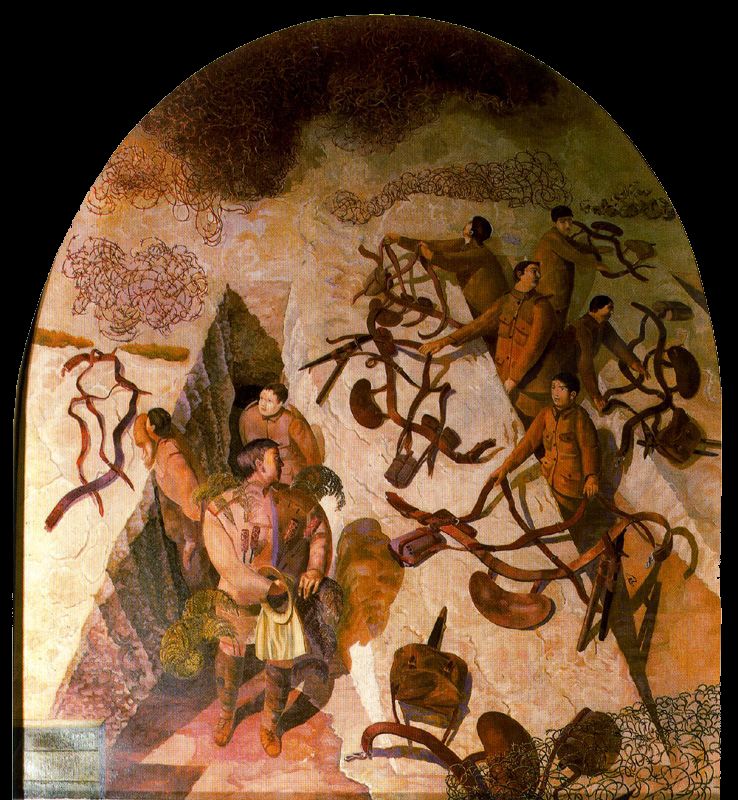

Dug Out (pictured above) is set at the front in Salonika with soldiers standing in two trenches with their equipment laid out in front of them, their sergeant, his own uniform partly camouflaged, looking toward them; barbed wire is at the front of the image. The mood is both tense and curiously serene: Spencer wrote that he had thought how marvellous it would be if one morning we came out of our dug-outs, and somehow everything was at peace and war had ended. Reveille is also a concatenation of contradictory moods. Soldiers are leaning into a vast tent, announcing that the war is over; at the apex of the tent there are clusters of scores of insects, menacing yet passive. The tent is filled with three standing figures wrapped in elaborate mosquito nets, like transparent graves, seemingly about to burst free from their entanglement. In Spencer’s iconography, these awakened but still entrapped figures may not only soon be free, but even redeemed.

Dug Out (pictured above) is set at the front in Salonika with soldiers standing in two trenches with their equipment laid out in front of them, their sergeant, his own uniform partly camouflaged, looking toward them; barbed wire is at the front of the image. The mood is both tense and curiously serene: Spencer wrote that he had thought how marvellous it would be if one morning we came out of our dug-outs, and somehow everything was at peace and war had ended. Reveille is also a concatenation of contradictory moods. Soldiers are leaning into a vast tent, announcing that the war is over; at the apex of the tent there are clusters of scores of insects, menacing yet passive. The tent is filled with three standing figures wrapped in elaborate mosquito nets, like transparent graves, seemingly about to burst free from their entanglement. In Spencer’s iconography, these awakened but still entrapped figures may not only soon be free, but even redeemed.

The exhibition, in three galleries, is of course not the same as when visiting the chapel, where the viewer is literally and metaphorically absorbed in these teeming scenes of hope and despair, suffering and redemption.

However, the chapel is necessarily dimly lit, its details hard to see. Somerset House provides an unrepeatable experience, as we are able to see the newly restored paintings close up in bright light, appreciate the dizzying changes of scale, and the detail, often almost exquisite, of tent and military uniform and kit, the sand and arid landscape of Macedonia, the prison-like aspect of the Bristol hospital, the explosions of foliage and blossom. All is in a restricted range of colours – ochres, reds, rusts, browns, whites, occasional deep blues – which nevertheless convey bursts of light. Facial expressions are almost uniformly wooden, any liveliness apparent in body language. Spencer, through his own intensely idiosyncratic, eccentric, inimitable idiom, somehow conveys a range of expressions from acceptance, through resignation, to hope. He continually plays with the passive – the sleeping men – and the active, the hospital orderlies, the soldiers anticipating action.

Above all, in his elaborate, crowded, convincing compositions, Spencer is attentive to conveying through a myriad of details, the men at the heart of war – and peace.

![SEX MONEY RACE RELIGION [2016] by Gilbert and George. Installation shot of Gilbert & George 21ST CENTURY PICTURES Hayward Gallery](/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail_125_x_125_/public/mastimages/Gilbert%20%26%20George_%2021ST%20CENTURY%20PICTURES.%20SEX%20MONEY%20RACE%20RELIGION%20%5B2016%5D.%20Photo_%20Mark%20Blower.%20Courtesy%20of%20the%20Gilbert%20%26%20George%20and%20the%20Hayward%20Gallery._0.jpg?itok=3oW-Y84i)

Add comment