Steve McQueen, Tate Modern review – films that stick in the mind | reviews, news & interviews

Steve McQueen, Tate Modern review – films that stick in the mind

Steve McQueen, Tate Modern review – films that stick in the mind

Memorable artist's films by the award winning director

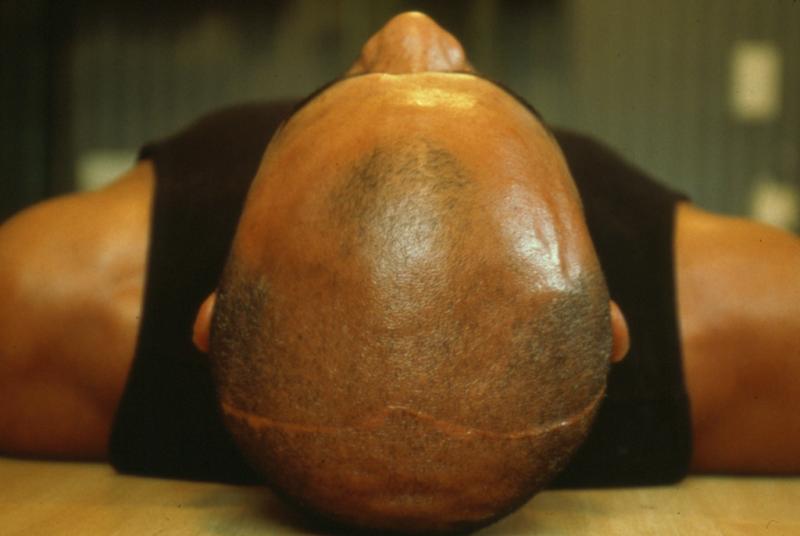

The screen is filled with the head and shoulders of a man lying on his back; he could be dead in the morgue or lying on the analyst’s couch. He doesn’t move (it’s a still), but we hear his voice recounting the terrible story of the day he accidentally killed his brother.

7th Nov. (main picture) lasts 23 minutes – long enough for you to examine every follicle on the man’s scalp, while at the same time picturing each detail of the horrific tale. The film demonstrates the amazing power of words to trigger mental pictures, while also highlighting the difference between seeing and imagining. The story is gripping; you feel trapped inside the nightmare alongside the narrator, whose name is Marcus. He is Steve McQueen’s cousin.

McQueen is best known for feature films like 12 Years a Slave which, in 2013, won an Oscar, a BAFTA and Golden Globe award. McQueen first made his name, though, as an artist. In 1999 he won the Turner Prize and this survey at Tate Modern is of films he has made as an artist since then.

What, then, can one expect; what’s the difference between a mainstream movie and an artist’s film? A film maker obviously has greater freedom and independence if box office returns are not an issue. S/he can take more risks and demand more from the viewer; instead of having to attract an audience, s/he can require you to make more effort to meet them half way.

As with 7th Nov. the experience can be incredibly rewarding, but it can also be hard work and, at its most extreme, the audience can seem all but superfluous. Take End Credits (pictured above), for instance. Since 2012, McQueen has scanned thousands of documents obtained from the FBI under the Freedom of Information act. They record the surveillance of Paul Robeson, the black American singer and activist they suspected of being a member of the Communist Party. Over a period of 37 years, Robeson’s every move was monitored, producing reams of material. McQueen’s project is ongoing, but the film footage already lasts five and half hours.

As with 7th Nov. the experience can be incredibly rewarding, but it can also be hard work and, at its most extreme, the audience can seem all but superfluous. Take End Credits (pictured above), for instance. Since 2012, McQueen has scanned thousands of documents obtained from the FBI under the Freedom of Information act. They record the surveillance of Paul Robeson, the black American singer and activist they suspected of being a member of the Communist Party. Over a period of 37 years, Robeson’s every move was monitored, producing reams of material. McQueen’s project is ongoing, but the film footage already lasts five and half hours.

Watching it is a chilling reminder of the state’s ability to invade the private lives of citizens. As the pages scroll past, a voice reads extracts from documents recording private meetings and phone calls as well as public appearances, interviews and newspaper coverage. Since then surveillance technology has become increasingly sophisticated and police and local authorities are demanding ever more powers to use it, so End Credits is incredibly timely. Yet no-one is likely to watch more than ten minutes of it.

You could say this makes it redundant, another example of an artist’s film that shows scant regard for the viewer; yet it lingers in the mind, invading one’s thoughts far more profoundly than most movies. It may not be one’s idea of entertainment, but the project feels important and necessary. And it colours one’s response to McQueen’s Static 2009 (pictured above). Filmed from a helicopter as it circles the Statue of Liberty, the footage takes us close enough to the monument to see how ugly it is and to appreciate how hollow it is, both physically and in terms of the promises it represents.

You could say this makes it redundant, another example of an artist’s film that shows scant regard for the viewer; yet it lingers in the mind, invading one’s thoughts far more profoundly than most movies. It may not be one’s idea of entertainment, but the project feels important and necessary. And it colours one’s response to McQueen’s Static 2009 (pictured above). Filmed from a helicopter as it circles the Statue of Liberty, the footage takes us close enough to the monument to see how ugly it is and to appreciate how hollow it is, both physically and in terms of the promises it represents.

End Credits also makes Once Upon A Time, 2002 as hard to swallow as the froth on a cappuccino. Originally selected by NASA in the 1970s to represent life on earth, this sequence of images was sent into space on the Voyager I and II missions and is still travelling through the universe. Following one another in apparently random succession, we see arithmetic equations and musical scores, diagrams explaining reproduction and childbirth, pictures of a foetus, astronaut and string quartet, skyscrapers, supermarket shelves, plants and a rocket taking off. McQueen has added a soundtrack spoken in gobbledygook, an apt response to this saccharine resumé of human life which ignores famine, war, sickness or any other form of hardship. His title, Once Upon A Time is a reminder of how we use myths and stories to dupe one another and even ourselves.

Bringing McQueen’s films together like this reveals his propensity for capturing the dark side of life. Ashes, 2002-15, is a two part film (pictured below) recording the carefree life and untimely murder of a fisherman from Grenada. We see him silhouetted against the blue sky, perched on the prow of his boat as it floats lazily towards the horizon. Life is a breeze, or so it seems; but on the soundtrack we learn of an inadvertent encounter with drug dealers who shoot to kill and, on the other side of the screen, we encounter the flip side of the story – the preparation of Ashes’ grave and headstone.

Western Deep, 2002 goes three and a half kilometres underground into the deepest gold mine in the world, where 5,000 people toil in temperatures reaching 90 degrees celsius. Juxtaposing extreme noise with absolute silence, and total darkness with beautiful shots of faces lit by torchlight or silhouetted against the wire of the cage lift, McQueen takes us on an impressionistic journey into this South African hell hole. If conditions in the pit are dire, above ground, the premises and regime resemble a prison. To maintain levels of fitness, off-duty miners are required to do hundreds of step ups in time with the relentless rhythm of flashing lights and screeching bells. You see exhausted men slumped on benches, their faces numb with fatigue, and you emerge from the film similarly numbed by the ordeal you’ve witnessed but, thankfully, are unlikely to experience.

Western Deep, 2002 goes three and a half kilometres underground into the deepest gold mine in the world, where 5,000 people toil in temperatures reaching 90 degrees celsius. Juxtaposing extreme noise with absolute silence, and total darkness with beautiful shots of faces lit by torchlight or silhouetted against the wire of the cage lift, McQueen takes us on an impressionistic journey into this South African hell hole. If conditions in the pit are dire, above ground, the premises and regime resemble a prison. To maintain levels of fitness, off-duty miners are required to do hundreds of step ups in time with the relentless rhythm of flashing lights and screeching bells. You see exhausted men slumped on benches, their faces numb with fatigue, and you emerge from the film similarly numbed by the ordeal you’ve witnessed but, thankfully, are unlikely to experience.

McQueen’s exhibition is not for the faint heated. Those expecting the sound of music, will be appalled by the clanking of heavy machinery and those wanting happy endings will go home disappointed. With no denouement, there’s no catharsis, so the thoughts and feelings engendered by the work stay with you, nibbling at your brain. You are not let off the hook and that, I would argue, is one of the key differences between a mainstream movie and an artist’s film.

rating

Explore topics

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Visual arts

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

Lee Miller, Tate Britain review - an extraordinary career that remains an enigma

Fashion photographer, artist or war reporter; will the real Lee Miller please step forward?

Lee Miller, Tate Britain review - an extraordinary career that remains an enigma

Fashion photographer, artist or war reporter; will the real Lee Miller please step forward?

Kerry James Marshall: The Histories, Royal Academy review - a triumphant celebration of blackness

Room after room of glorious paintings

Kerry James Marshall: The Histories, Royal Academy review - a triumphant celebration of blackness

Room after room of glorious paintings

Folkestone Triennial 2025 - landscape, seascape, art lovers' escape

Locally rooted festival brings home many but not all global concerns

Folkestone Triennial 2025 - landscape, seascape, art lovers' escape

Locally rooted festival brings home many but not all global concerns

Sir Brian Clarke (1953-2025) - a personal tribute

Remembering an artist with a gift for the transcendent

Sir Brian Clarke (1953-2025) - a personal tribute

Remembering an artist with a gift for the transcendent

Emily Kam Kngwarray, Tate Modern review - glimpses of another world

Pictures that are an affirmation of belonging

Emily Kam Kngwarray, Tate Modern review - glimpses of another world

Pictures that are an affirmation of belonging

Kiefer / Van Gogh, Royal Academy review - a pairing of opposites

Small scale intensity meets large scale melodrama

Kiefer / Van Gogh, Royal Academy review - a pairing of opposites

Small scale intensity meets large scale melodrama

Jenny Saville: The Anatomy of Painting, National Portrait Gallery review - a protégé losing her way

A brilliant painter in search of a worthwhile subject

Jenny Saville: The Anatomy of Painting, National Portrait Gallery review - a protégé losing her way

A brilliant painter in search of a worthwhile subject

Abstract Erotic, Courtauld Gallery review - sculpture that is sensuous, funny and subversive

Testing the boundaries of good taste, and winning

Abstract Erotic, Courtauld Gallery review - sculpture that is sensuous, funny and subversive

Testing the boundaries of good taste, and winning

Edward Burra, Tate Britain review - watercolour made mainstream

Social satire with a nasty bite

Edward Burra, Tate Britain review - watercolour made mainstream

Social satire with a nasty bite

Ithell Colquhoun, Tate Britain review - revelations of a weird and wonderful world

Emanations from the unconscious

Ithell Colquhoun, Tate Britain review - revelations of a weird and wonderful world

Emanations from the unconscious

Rachel Jones: Gated Canyons, Dulwich Picture Gallery review - teeth with a real bite

Mouths have never looked so good

Rachel Jones: Gated Canyons, Dulwich Picture Gallery review - teeth with a real bite

Mouths have never looked so good

Add comment