Tacita Dean: Portrait, National Portrait Gallery / Still Life, National Gallery review - film as a fine art | reviews, news & interviews

Tacita Dean: Portrait, National Portrait Gallery / Still Life, National Gallery review - film as a fine art

Tacita Dean: Portrait, National Portrait Gallery / Still Life, National Gallery review - film as a fine art

Films whose beauty is more akin to painting than to cinema

Sometimes you come across an artwork that changes the way you see the world. Tacita Dean’s film portrait of the American choreographer Merce Cunningham (main picture) is one such encounter.

In 1952 Cunningham’s partner, the composer John Cage, (in)famously produced 4’ 33”: it required an audience to listen for four and a half minutes to the ambient sounds filtering into the concert hall while an orchestra sat silently by. The piece is in three movements and Dean’s installation Merce Cunningham Performs Stillness, 2008 shows Cunningham attending to each movement twice, while on the soundtrack the noise of urban life infiltrates the space.  The installation pays tribute both to Cunningham, who died the following year, and his legendary partnership with Cage, but it also does for film what 4’ 33” did for music. Cage wanted people to pay attention to the act of listening and, by allowing the world to intrude, Dean invites us to become aware of the complexity of viewing. We see Cunningham indistinctly – at a distance, from the side, in poor light or reflected in a mirror covered with finger prints that surround him with refracted light and blur his image. While he sits, you walk. And as you move, you interrupt the light from the projectors and so cast dark shadows across the screens.

The installation pays tribute both to Cunningham, who died the following year, and his legendary partnership with Cage, but it also does for film what 4’ 33” did for music. Cage wanted people to pay attention to the act of listening and, by allowing the world to intrude, Dean invites us to become aware of the complexity of viewing. We see Cunningham indistinctly – at a distance, from the side, in poor light or reflected in a mirror covered with finger prints that surround him with refracted light and blur his image. While he sits, you walk. And as you move, you interrupt the light from the projectors and so cast dark shadows across the screens.

Its a frustrating experience, until you realise that this is precisely the point. The relationship between viewer and film has been reversed. Instead of an audience quietly watching on-screen action, the gallery is busy with the movement of people, the whirring of motors and the clicking of film going through gates while, on screen, there is only focused stillness and concentration.

Dean chooses film as her medium, yet her images are more akin to paintings than to cinema. When there is a narrative, it unfolds so slowly that time becomes an almost tangible element, with one’s eye encouraged to linger over the beauty of the textures, colours and light of each frame.

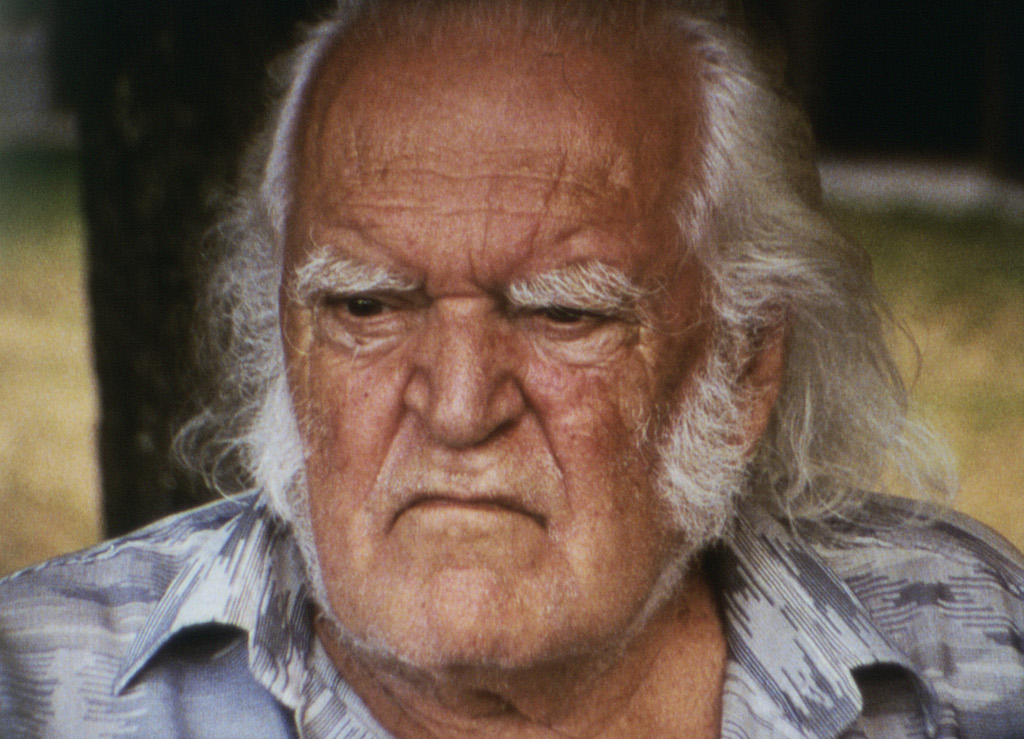

The artist has two exhibitions running concurrently; one is titled Portrait (at the NPG) and the other Still Life (at the National Gallery), but she deliberately blurs the boundaries between the two genres. Her sitters, mostly venerable old men, are stilled while, in contrast, her still lives are animated by changes in light, weather, viewpoint and camera angle. The Italian sculptor Mario Merz (pictured above) sits in a courtyard sheltered from the sun by a large tree that envelops him in dappled shade. We can hardly see his face, but he is clearly uncomfortable being watched, and squirms under the unflinching gaze of the camera. David Hockney (pictured below) is more relaxed. During the 16 minutes we spend with him in his studio, he smokes five cigarettes and laughingly remarks, “It is very enjoyable, smoking; that’s why it won’t go away!”

The artist has two exhibitions running concurrently; one is titled Portrait (at the NPG) and the other Still Life (at the National Gallery), but she deliberately blurs the boundaries between the two genres. Her sitters, mostly venerable old men, are stilled while, in contrast, her still lives are animated by changes in light, weather, viewpoint and camera angle. The Italian sculptor Mario Merz (pictured above) sits in a courtyard sheltered from the sun by a large tree that envelops him in dappled shade. We can hardly see his face, but he is clearly uncomfortable being watched, and squirms under the unflinching gaze of the camera. David Hockney (pictured below) is more relaxed. During the 16 minutes we spend with him in his studio, he smokes five cigarettes and laughingly remarks, “It is very enjoyable, smoking; that’s why it won’t go away!”

Dean has devised a system of masking that enables her to expose one section of celluloid at a time. This allowed her to film three Shakespearean actors – Stephen Dillane, David Warner and Ben Wishaw – on the same reel, as though they were side by side when, in fact, they were hundreds of miles apart. Projected in miniature, these intense little portraits are displayed alongside miniatures from the collection by luminaries such as Nicholas Hilliard.  The poet Michael Hamburger describes the apples he grows in the orchards around his house; filming in ambient light, the camera dwells on his gnarled hands, on serried rows of apples, piles of books and the light diffused by dirty windows, as music filters through closed doors. Time trickles slowly in a portrait comprised of a string of exquisite moments, or numerous still lives.

The poet Michael Hamburger describes the apples he grows in the orchards around his house; filming in ambient light, the camera dwells on his gnarled hands, on serried rows of apples, piles of books and the light diffused by dirty windows, as music filters through closed doors. Time trickles slowly in a portrait comprised of a string of exquisite moments, or numerous still lives.

Conversely, in Prisoner Pair 2008 (pictured above left), a still life of two pears slowly dissolving in schnapps at the National Gallery, one is made aware of time passing through differing camera angles, changes in the opalescent glimmer of light on liquid, fruit and glass, and watching particles of sediment drift through clear spirits. In one shot, the curved glass reminded me of our planet drifting in solitary splendour through the solar system.

To accompany her films, Dean has chosen still life paintings mainly from the collection. These encourage one to recall that, traditionally, a still life was an invitation to contemplate the brevity of life while, at the same time, delighting in the beauty of the material world and the artists’s ability to capture its nuances. Still Life with Bottle, Glass and Loaf by a Victorian follower of Chardin is also laced with religious symbolism, while William Henry Hunt’s watercolour of two apples is a celebration of the colour, texture and shape of this symbolic fruit.  In the adjoining room Dean’s film Ideas for Sculpture in a Setting, 2017, is projected; shot in black and white, it looks like an art documentary from the 1950s. Filmed in close-up on the grass is a flint from the collection of the sculptor Henry Moore. Things change continually; cows wander past, clouds hang overhead, and sunlight beams through the holes; and depending on the light, the pitted surface of the stone variously resembles bone, peeling skin or torn bread. At no point is one given any sense of scale, though; the object under scrutiny could be a tiny stone or one of Moore’s large public sculptures. By means of deliberate ambiguity, the film elucidates the creative process through which a small flint picked up on a beach might become the inspiration for a major body of work.

In the adjoining room Dean’s film Ideas for Sculpture in a Setting, 2017, is projected; shot in black and white, it looks like an art documentary from the 1950s. Filmed in close-up on the grass is a flint from the collection of the sculptor Henry Moore. Things change continually; cows wander past, clouds hang overhead, and sunlight beams through the holes; and depending on the light, the pitted surface of the stone variously resembles bone, peeling skin or torn bread. At no point is one given any sense of scale, though; the object under scrutiny could be a tiny stone or one of Moore’s large public sculptures. By means of deliberate ambiguity, the film elucidates the creative process through which a small flint picked up on a beach might become the inspiration for a major body of work.

The film is a diptych and hung between the two screens is Paul Nash’s painting Event on the Downs, 1934 (pictured above) which portrays the meeting of a tennis ball and gnarled tree trunk above chalk cliffs, as a cloud resembling a lump of flint drifts overhead. The Surrealism of this still life/landscape is brought into sharp focus by Dean’s atmospheric film. The juxtapositions enrich both painting and film; do not miss these thought-provoking dialogues.

rating

Explore topics

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Visual arts

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

![SEX MONEY RACE RELIGION [2016] by Gilbert and George. Installation shot of Gilbert & George 21ST CENTURY PICTURES Hayward Gallery](https://theartsdesk.com/sites/default/files/styles/thumbnail/public/mastimages/Gilbert%20%26%20George_%2021ST%20CENTURY%20PICTURES.%20SEX%20MONEY%20RACE%20RELIGION%20%5B2016%5D.%20Photo_%20Mark%20Blower.%20Courtesy%20of%20the%20Gilbert%20%26%20George%20and%20the%20Hayward%20Gallery._0.jpg?itok=7tVsLyR-) Gilbert & George, 21st Century Pictures, Hayward Gallery review - brash, bright and not so beautiful

The couple's coloured photomontages shout louder than ever, causing sensory overload

Gilbert & George, 21st Century Pictures, Hayward Gallery review - brash, bright and not so beautiful

The couple's coloured photomontages shout louder than ever, causing sensory overload

Lee Miller, Tate Britain review - an extraordinary career that remains an enigma

Fashion photographer, artist or war reporter; will the real Lee Miller please step forward?

Lee Miller, Tate Britain review - an extraordinary career that remains an enigma

Fashion photographer, artist or war reporter; will the real Lee Miller please step forward?

Kerry James Marshall: The Histories, Royal Academy review - a triumphant celebration of blackness

Room after room of glorious paintings

Kerry James Marshall: The Histories, Royal Academy review - a triumphant celebration of blackness

Room after room of glorious paintings

Folkestone Triennial 2025 - landscape, seascape, art lovers' escape

Locally rooted festival brings home many but not all global concerns

Folkestone Triennial 2025 - landscape, seascape, art lovers' escape

Locally rooted festival brings home many but not all global concerns

Sir Brian Clarke (1953-2025) - a personal tribute

Remembering an artist with a gift for the transcendent

Sir Brian Clarke (1953-2025) - a personal tribute

Remembering an artist with a gift for the transcendent

Emily Kam Kngwarray, Tate Modern review - glimpses of another world

Pictures that are an affirmation of belonging

Emily Kam Kngwarray, Tate Modern review - glimpses of another world

Pictures that are an affirmation of belonging

Kiefer / Van Gogh, Royal Academy review - a pairing of opposites

Small scale intensity meets large scale melodrama

Kiefer / Van Gogh, Royal Academy review - a pairing of opposites

Small scale intensity meets large scale melodrama

Jenny Saville: The Anatomy of Painting, National Portrait Gallery review - a protégé losing her way

A brilliant painter in search of a worthwhile subject

Jenny Saville: The Anatomy of Painting, National Portrait Gallery review - a protégé losing her way

A brilliant painter in search of a worthwhile subject

Abstract Erotic, Courtauld Gallery review - sculpture that is sensuous, funny and subversive

Testing the boundaries of good taste, and winning

Abstract Erotic, Courtauld Gallery review - sculpture that is sensuous, funny and subversive

Testing the boundaries of good taste, and winning

Edward Burra, Tate Britain review - watercolour made mainstream

Social satire with a nasty bite

Edward Burra, Tate Britain review - watercolour made mainstream

Social satire with a nasty bite

Ithell Colquhoun, Tate Britain review - revelations of a weird and wonderful world

Emanations from the unconscious

Ithell Colquhoun, Tate Britain review - revelations of a weird and wonderful world

Emanations from the unconscious

Add comment