theartsdesk in Dublin: St Patrick's Day Festival 2011 | reviews, news & interviews

theartsdesk in Dublin: St Patrick's Day Festival 2011

theartsdesk in Dublin: St Patrick's Day Festival 2011

Craic and culture make for an intoxicating combination on a literary pilgrimage to Dublin

“What’s the story?” It’s a question you’ll hear again and again in the streets and pubs of Dublin. You can tell a lot about a nation from their greeting; the traditional salutation of northern China, born of decades of famine and physical hardship, translates to “Have you eaten?”, and a psychologist could extrapolate much from our English fondness for impersonal, weather-related pleasantries. So it’s surely no coincidence then that Ireland, and Dublin in particular, should favour this conversational opener. A city home to some 50 publishing houses, that has produced four Nobel Laureates, arguably the greatest Modernist novel, and was recently named a UNESCO City of Literature: Scheherazade has nothing on Dublin.

It’s 16 March, the eve of St Patrick’s Day, and I’m walking past Dublin’s National Library and down towards St Stephen’s Green. It’s five o’clock, still implausibly sunny, and the pulsing, metallic whine of amplified music tells of a party already well underway. As I near the square cheers overtake the music, and a stage reveals small pink girls in big green outfits giggling madly as they attempt a folk song into an outstretched microphone. The crowd encourages them noisily, and both music and applause carry out across the park, continuing into the night – the warm-up act for Ireland’s biggest and best-known festival.

St Patrick’s Day is famous internationally as a day of celebration and carousing, of brightly coloured costumes and more Guinness than is good for you. All about the craic, culture was once exiled to the more rarified literary festivities of Bloomsday in June, but no longer. With the Festival growing each year, offshoots of literature and music, theatre and art, have all sprung up around the iconic parade, and this year’s UNESCO’s designation has proved perhaps the biggest catalyst yet for a growing integration of culture and celebration.

Of Dublin’s litany of contemporary authors it is Roddy Doyle, Booker Prize-winning author of Paddy Clarke Ha Ha Ha, who was chosen to pen the first ever short story for the St Patrick’s Day parade. Rejecting the exotic themes of previous years, Doyle’s Brilliant directs its gaze back on Dublin itself and, even more bravely, to the less than rosy state of the Irish economy. Recession and redundancy are hardly natural choices for a celebration, but somehow the associative energy of Doyle’s imagination, and the caustic vernacular of his language, creates a work both honest and joyous: authentically and unashamedly Irish.

Of Dublin’s litany of contemporary authors it is Roddy Doyle, Booker Prize-winning author of Paddy Clarke Ha Ha Ha, who was chosen to pen the first ever short story for the St Patrick’s Day parade. Rejecting the exotic themes of previous years, Doyle’s Brilliant directs its gaze back on Dublin itself and, even more bravely, to the less than rosy state of the Irish economy. Recession and redundancy are hardly natural choices for a celebration, but somehow the associative energy of Doyle’s imagination, and the caustic vernacular of his language, creates a work both honest and joyous: authentically and unashamedly Irish.

Telling the tale of Raymond and Gloria, two children who lead a quest to vanquish the Black Dog of depression and recapture Dublin’s funny bone, Brilliant is no straightforward story to stage. Touring the backstage preparations, I am struck by the mechanical complexity of the floats, as well as their detail. The giant phoenix who will eventually carry off the Black Dog into the sky is a miracle of carefully shaded and textured plumage, but it is the moving jaws of the Dog himself (pictured below, complete with protruding papier-mâché teeth) that will later draw yelps from the children in the crowd, his memory only soothed by a flurry of neon-bright flamingos and a splendid 10 foot polar bear complete with his own moving plunge pool.

Assembled later on the top deck of the Brilliant bus, at the very head of the parade, we make our way slowly forwards through the city. The veins of the streets stretch ahead, stained green by the half a million people clustered on pavements, at windows, and even perched on the laps of statues. Marching bands and mounted policemen (followed by a man whose wheelie bin and broom proclaim him the possessor of the worst parade job) give way to dancing children in orange costumes – the wriggling phoenix flames brought to life – and finally to the underwater creatures of the Liffey. The crowds wave and shout, and from street to street the cry of “Brilliant!” (sometimes joyful, sometimes authentically ironic in spirit – a sarcastic verbal tomato hurled at our bus of unknowns) passes onwards, past Trinity College and into the heart of the city.

Assembled later on the top deck of the Brilliant bus, at the very head of the parade, we make our way slowly forwards through the city. The veins of the streets stretch ahead, stained green by the half a million people clustered on pavements, at windows, and even perched on the laps of statues. Marching bands and mounted policemen (followed by a man whose wheelie bin and broom proclaim him the possessor of the worst parade job) give way to dancing children in orange costumes – the wriggling phoenix flames brought to life – and finally to the underwater creatures of the Liffey. The crowds wave and shout, and from street to street the cry of “Brilliant!” (sometimes joyful, sometimes authentically ironic in spirit – a sarcastic verbal tomato hurled at our bus of unknowns) passes onwards, past Trinity College and into the heart of the city.

Early the next morning I retrace the route, taking a closer look at the city’s morning-after face. Barring the odd beer can there’s little evidence of yesterday’s festivities. The traces that linger are far less literal; you step over a gutter and wonder whether James Joyce sought relief in it after a hard night’s drinking, your feet click on cobbles and echo with the businesslike tread of Synge on his way to a rehearsal at the Abbey Theatre. An 18th-century townhouse in Parnell Square offers these ghosts an elegant home in the Dublin Writers Museum, its glassed cabinets and nostalgia balanced by the living practicality of next door’s Irish Writers Centre, a working hub for the city’s current generation of creatives.

For all the lures of the Northside, I find myself walking on, back across the Liffey towards Dublin Castle and one of my favourite museums in the world – the Chester Beatty Library. There’s something about a one-man collection, the relationships between its objects, the tastes they reflect and the character they reveal in their collector, that lends particular fascination to these galleries. A mining engineer from turn-of-the-century New York, Alfred Chester Beatty spent his time and self-made fortune travelling the world. A childhood collection of stamps and snuff bottles became an adult fascination for manuscripts, and the result is a collection that houses among its Eastern artefacts and Western prints some of the earliest surviving Gospel texts in any language – fragments that have materially shaped our newest translations today.

A copy of the Book of Deuteronomy from 150 AD is skin-tighteningly fragile. Individual fibrous strands – the ribs of the papyrus – are exposed, barely linking the flesh of one sentence to another. Buddhism, Islam, Sikhism and Hinduism are also reflected in the permanent collection, which moves from tiny zushi (miniature carved shrines for Buddhist monks and pilgrims) to vast, intricately woven textile mandalas and a 13th-century Qur’an.

A copy of the Book of Deuteronomy from 150 AD is skin-tighteningly fragile. Individual fibrous strands – the ribs of the papyrus – are exposed, barely linking the flesh of one sentence to another. Buddhism, Islam, Sikhism and Hinduism are also reflected in the permanent collection, which moves from tiny zushi (miniature carved shrines for Buddhist monks and pilgrims) to vast, intricately woven textile mandalas and a 13th-century Qur’an.

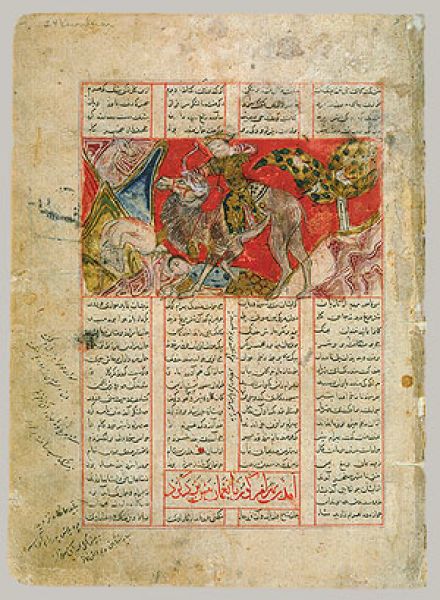

The downstairs galleries play host to exhibitions, showcasing the scope of the collection. A visit several years ago yielded prints by Albrecht Dürer, but the current exhibition (running until 3 April, 2011) looks to the East, to Beatty’s 23 copies of Firdawsi’s Shahnama (14th-century illustrated Shahnama pictured right). This Iranian “Book of Kings” is a national epic that offers both a guide to morality and kingship and a dramatic adventure story.

Spanning five centuries, the manuscripts in the collection develop in style and structure, each refracting the same classic stories of death and revenge through a different visual aesthetic (the effete and deeply pretty warriors of the 19th century would stand no chance against the vivid, brutal little figures of the 14th). They all share however a love of colour and pattern, perhaps explaining their visual appeal to magpie Beatty. Floors are covered with geometrically printed rugs, castle walls are tiled and panelled, and battlefields are rich with flowers and foliage. Details of historical context and conservation supplement this beautifully curated exhibition, explaining the particular problems of the yellow pigment (obtained from the urine of cows fed solely on mango leaves apparently) and the origins of the game of chess as illustrated cryptically in the manuscripts.

Moments down the road, tucked behind St Patrick’s Cathedral, is another of Dublin’s lesser-known literary treasures. Marsh’s Library (named after its founder, the 17th-century Archbishop of Dublin so articulately despised by Jonathan Swift) is the oldest public library in Ireland. Two narrow galleries still house their volumes of natural history, music, science, literature and geography on their original shelves – indeed you could return a volume of travel writing to the same shelf from which Swift himself removed it while researching Gulliver’s Travels. The chains that once shackled the books to the wall have now been removed, the single concession to modernity, but the cages designed to secure each reader into his cubbyhole (the “stagnant bay” vividly described in Joyce’s Ulysses) are still in place, presided over by the all-knowing librarian Muriel McCarthy.

Home to an exhibition that changes annually each June, the library has recently displayed its collections of musical manuscripts, early women’s writings, botanical illustrations and works of natural history. Currently lively with viscera and other anatomical delights, it is the turn of the library’s medical texts in the spotlight. Exploring early pharmacology, obstetrics, quackery and surgery, the works range from a 17th-century edition of Hippocrates and René Descartes’s De homine figuris (complete with alarmingly protruding 3D illustrations), an early guide to female anatomy (written originally in French but published in Latin for fear of obscenity), and disturbing illustrations of experimental surgeries, in which Christ-like patients submit to the ghastly attentions of whole packs of doctors.

Home to an exhibition that changes annually each June, the library has recently displayed its collections of musical manuscripts, early women’s writings, botanical illustrations and works of natural history. Currently lively with viscera and other anatomical delights, it is the turn of the library’s medical texts in the spotlight. Exploring early pharmacology, obstetrics, quackery and surgery, the works range from a 17th-century edition of Hippocrates and René Descartes’s De homine figuris (complete with alarmingly protruding 3D illustrations), an early guide to female anatomy (written originally in French but published in Latin for fear of obscenity), and disturbing illustrations of experimental surgeries, in which Christ-like patients submit to the ghastly attentions of whole packs of doctors.

Crossing the beautiful Samuel Beckett bridge (pictured above) back into the present day, I move from Ireland’s oldest public library to one of its newest landmarks, to conclude my pilgrimage in Dublin’s contemporary literary landscape. There could be few more apt or lovely symbols of hope for Ireland’s cultural future than the Dublin Convention Centre, designed and completed last year by American-Irish architect Kevin Roche. Illuminated in green for the Festival, its curved atrium coils upwards to deliver views over the city that rival those of the celebrated Guinness Storehouse, though admittedly without the ambient enhancement of a pint in hand.

Crossing the beautiful Samuel Beckett bridge (pictured above) back into the present day, I move from Ireland’s oldest public library to one of its newest landmarks, to conclude my pilgrimage in Dublin’s contemporary literary landscape. There could be few more apt or lovely symbols of hope for Ireland’s cultural future than the Dublin Convention Centre, designed and completed last year by American-Irish architect Kevin Roche. Illuminated in green for the Festival, its curved atrium coils upwards to deliver views over the city that rival those of the celebrated Guinness Storehouse, though admittedly without the ambient enhancement of a pint in hand.

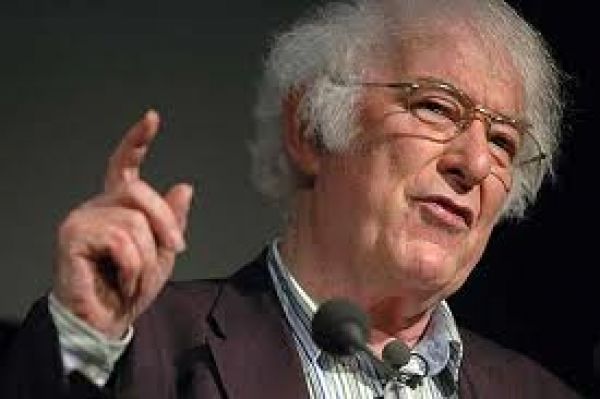

Sebastian Barry; Joseph O’Connor: Roddy Doyle; Neil Jordan; Seamus Heaney (pictured above); lacking only perhaps Brian Friel for a Royal Flush of Irish literary talent, the DublinSwell celebration could not have offered a more persuasive case for the UNESCO designation it honoured. Joining Edinburgh, Melbourne and Iowa City (less anomalous when you remember the Iowa Writer’s Workshop and its associations with Vonnegut, Robert Lowell, John Irving and Orhan Pamuk) as a UNESCO City of Literature in perpetuity, Dublin’s celebration was a typically generous affair.

Striking for the polyphonic variety of its literary voices, the evening moved from comedy and satire in Paul Duncan’s verse and Jonathan Swift’s A Modest Proposal (delivered with relish and a set of carving knives by Eamon Morrissey), to the delicate tragedy of Oscar Wilde’s The Selfish Giant and Gerry Stembridge’s Unspoken. Ireland’s bards and her tradition of musical storytelling were celebrated in performances from Damien Dempsey and Mike Scott, while members of the Abbey Theatre company brought life to works by Marina Carr and Sean O’Casey.

A mongrel tradition of tones and influences, Irish literature shares much with the nation's musical tradition. Pulsing with syncopated stresses, the energy of Irish music comes from its cross-currents, from the rhythms that kick and stamp against the prevailing beat. The best of Irish literature – lyric where you might expect violence, its comedy jostling up against pathos or epic – shares this contrarian instinct, this tension. It’s there in Shaw, in Joyce, in Beckett, but also in Dublin itself. A city where craic and culture are all but interchangeable, where ancient manuscripts are housed alongside contemporary performance poets, Dublin goes about its business with a bottle of whiskey in one hand and a copy of Ulysses in the other. It’s an intoxicating combination, a joyously anarchic, defiantly inimitable model for any other would-be City of Literature.

- Read Brilliant on Roddy Doyle's website

- Heroes and Kings of the Shahnama is at the Chester Beatty Library until 3 April, 2011

- Hippocrates Revived is at Marsh's Library until June 2011

Find Roddy Doyle on Amazon

Find Roddy Doyle on Amazon

Share this article

Add comment

more Visual arts

Eye to Eye: Homage to Ernst Scheidegger, MASI Lugano review - era-defining artist portraits

One of Switzerland's greatest photographers celebrated with a major retrospective

Eye to Eye: Homage to Ernst Scheidegger, MASI Lugano review - era-defining artist portraits

One of Switzerland's greatest photographers celebrated with a major retrospective

Stephen review - a breathtakingly good first feature by a multi-media artist

Melanie Manchot's debut is strikingly intelligent and compelling

Stephen review - a breathtakingly good first feature by a multi-media artist

Melanie Manchot's debut is strikingly intelligent and compelling

Fantastic Machine review - photography's story from one camera to 45 billion

Love it or hate it, the photographic image has ensnared us all

Fantastic Machine review - photography's story from one camera to 45 billion

Love it or hate it, the photographic image has ensnared us all

Yinka Shonibare: Suspended States, Serpentine Gallery review - pure delight

Weighty subject matter treated with the lightest of touch

Yinka Shonibare: Suspended States, Serpentine Gallery review - pure delight

Weighty subject matter treated with the lightest of touch

Jane Harris: Ellipse, Frac Nouvelle-Aquitaine MÉCA, Bordeaux review - ovals to the fore

Persistence and conviction in the works of the late English painter

Jane Harris: Ellipse, Frac Nouvelle-Aquitaine MÉCA, Bordeaux review - ovals to the fore

Persistence and conviction in the works of the late English painter

Sargent and Fashion, Tate Britain review - portraiture as a performance

London’s elite posing dressed up to the nines

Sargent and Fashion, Tate Britain review - portraiture as a performance

London’s elite posing dressed up to the nines

Zineb Sedira: Dreams Have No Titles, Whitechapel Gallery review - a disorientating mix of fact and fiction

An exhibition that begs the question 'What and where is home?'

Zineb Sedira: Dreams Have No Titles, Whitechapel Gallery review - a disorientating mix of fact and fiction

An exhibition that begs the question 'What and where is home?'

Yoko Ono: Music of the Mind, Tate Modern review - a fitting celebration of the early years

Acknowledgement as a major avant garde artist comes at 90

Yoko Ono: Music of the Mind, Tate Modern review - a fitting celebration of the early years

Acknowledgement as a major avant garde artist comes at 90

Unravel: The Power and Politics of Textiles in Art, Barbican review - the fabric of dissent

An ambitious exploration of a neglected medium

Unravel: The Power and Politics of Textiles in Art, Barbican review - the fabric of dissent

An ambitious exploration of a neglected medium

When Forms Come Alive, Hayward Gallery review - how to reduce good art to family fun

Seriously good sculptures presented as little more than playthings or jokes

When Forms Come Alive, Hayward Gallery review - how to reduce good art to family fun

Seriously good sculptures presented as little more than playthings or jokes

Entangled Pasts 1768-now, Royal Academy review - an institution exploring its racist past

After a long, slow journey from invisibility to agency, black people finally get a look in

Entangled Pasts 1768-now, Royal Academy review - an institution exploring its racist past

After a long, slow journey from invisibility to agency, black people finally get a look in

Barbara Kruger, Serpentine Gallery review - clever, funny and chilling installations

Exploring the lies, deceptions and hyperbole used to cajole, bully and manipulate us

Barbara Kruger, Serpentine Gallery review - clever, funny and chilling installations

Exploring the lies, deceptions and hyperbole used to cajole, bully and manipulate us

Comments

...