A play could be written about, or for, Michael Gambon's fingers, and perhaps Beckett's 1958 Krapp's Last Tape is it. I've seen this solo piece many times, most recently in a studio theatre rendition from Harold Pinter that opened a window on to his own mortality and won't quickly be forgotten. But what Gambon brings to the table - well, desk - is the abiding sense of a man struggling for his share of the light amidst darkness at the very moment that his powers may be slipping away. Or are they? Only those fingers know for sure.

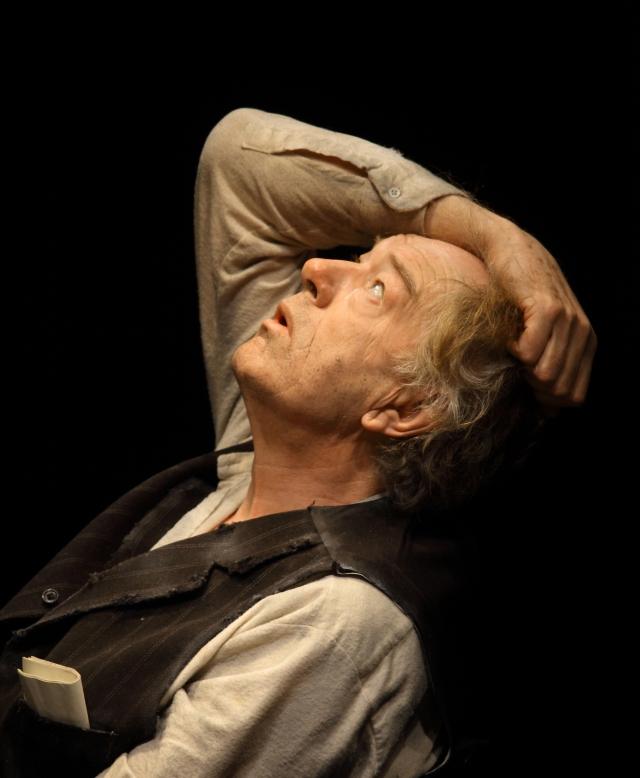

Indeed, during the opening passages of Michael Colgan's production, first seen in the spring at Dublin's Gate Theatre, Gambon's digits seem engaged in a drama all their own, extended for maximum effect so that the actor can, in effect, cup his own head in a capacious hand. Some years back Mel Gussow, the late American drama critic, wrote a lengthy profile of Gambon revealing the many and varied impersonations that the actor can manage with his fingers; there's a party trick we would love to see.

But there's more to this particular dramatic reverie than simply the mesmerising hold exerted on an audience by the singular manual capacities of an actor-knight too long absent from the London stage. (Gambon essayed Beckett four years ago in another, even shorter "dramaticule", Eh Joe). Much like James Joyce's The Dead, which Beckett's text resembles in its inexorable movement towards a deathly, almost marmoreal stillness, Krapp's Last Tape posits what looks to be its lone character's final face-off against a life that could at any moment be switched off, rather like the faintly ominous ceiling lamp shedding the sole illumination on an otherwise darkened stage.

Moving from rage to tears, regret to absolute unsentimentality, Krapp seems obsessed with the past, yet adrift in the present. "Nothing to say," he says (there's the Beckettian paradox for you in a nutshell), the 69-year-old succumbing to meditations on an "uninhabited earth" that would seem to portend his own extinction. If all this sounds too heavy by half, fear not, we're talking Beckett, which means an antic, vaudevillian spirit is rarely far from sight. You might wonder whether the stuff early on with the bananas is in the script; indeed it is, if not quite to the phallic degree to which the visuals are pushed here.

In fact, a vague fussiness, a tendency to overegg the exactingly conceived textual blueprint provided by Beckett, is my only complaint with a performance that also seems considerably longer than the brief but sustained roar achieved by Pinter. And how moving to see the playwright's widow, Lady Antonia Fraser, among this Krapp's starry if rather clamorous first-night crowd, an assemblage that would have done well to adopt some of the encompassing quiet found at the opening of Passion the previous night. "Extraordinary silence this evening," Krapp comments; alas, not from the stalls.

'Nothing to say,' he says (there's the Beckettian paradox for you in a nutshell)

On a purely emotive level, the staging's raison d'être is the return to our midst of The Great Gambon, not least in a play obsessed with memory here performed by a thespian titan who had been rumoured of late to have been having memory problems of his own (an irony not lost, surely, on an industry first-night crowd). In the event, Gambon has ascribed his own departure early in rehearsals from Alan Bennett's The Habit of Art to an ailment that, even to him, remains unexplained, which in turn lends added resonance to the dishevelled, wizened personage we see before us. Oh, and the fact that he and Krapp are the same age.

This actor has always embraced contradictions, all of which feed this performance fully. Granitic and yet graceful, his face communicating an eagerness for experience that nonetheless comes shadowed by fear, Gambon here seems to call up an entire generation of actors who appear on stage these days less and less. (When did you last see Albert Finney or Maggie Smith in a play?)

I could have done without the meta-theatrical business of Krapp grabbing at an ever-shifting spotlight - where's that in the text? - but I can't imagine dedicated playgoers not grabbing at this opportunity. "Perhaps my best years are gone," we hear Krapp ruminating on tape at roughly the same time that Gambon's face stiffens like some indelibly lined rock face. And before we get the right to reply, the lights go out. The rest, as Beckett made a career of reminding us, is silence.

Add comment