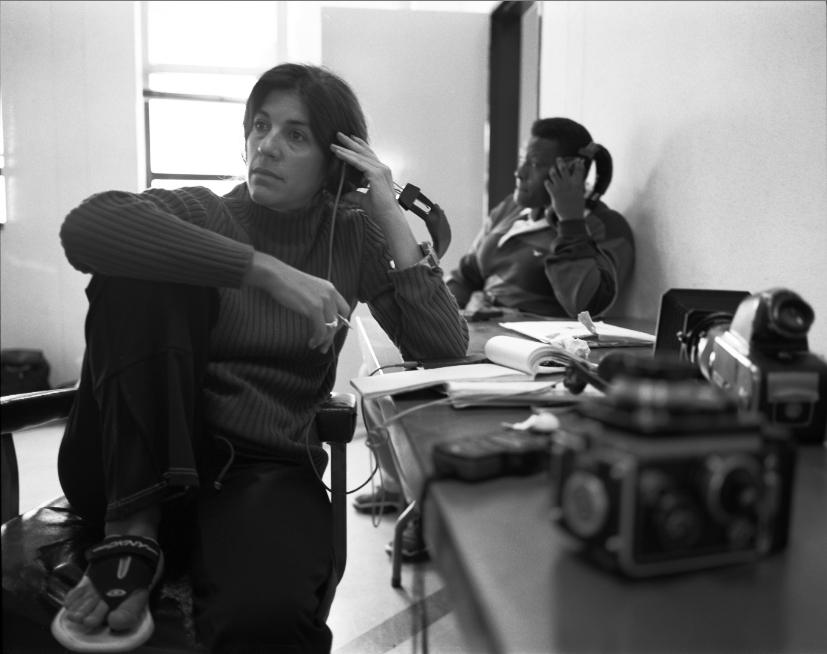

Jillian Edelstein, the distinguished photographer, is joining theartsdesk. She grew up in Cape Town and in 1985 moved to London, where within a year she had won the Kodak UK Young Photographer of the Year award. It was to be the first of many such accolades. She has since established a reputation as one of the leading portrait photographers of the age, her work appearing widely in this country but also for American publications including The New Yorker, Vanity Fair, Vogue and Interview.

Between 1996 and 2002 she documented the proceedings of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission in South Africa. The resulting book, Truth and Lies, was published by Granta in 2002. Earlier this year her work was exhibited at the National Portrait Gallery. She has currently completing her third long-term project about the sangoma, traditional healers who train in the mountains on the Lesotho-South Africa border. Here she talks about her work.

SUE STEWARD: Would it be accurate to describe your work in definable thematic chunks?

JILLIAN EDELSTEIN: It absolutely works in thematic chunks: photojournalism morphing into portraits, and then the two living alongside each other.

How did photography take a hold on you?

I would say that the beginning was understanding that I had a powerful visual response to things. And tangentially to that, discovering the magic of the dark room. It began at the University of Cape Town, where I was studying to become a social worker. It really began with my work in the townships, and also the fact that my background was very much ingrained in the political apartheid landscape. And there was also the influence of my parents, who were liberals and slightly alarmed by my endeavours to get involved politically. Which is why I think that photography suited me so well: it was a way in which I could, in some way, make a statement.

The first photographs I ever took that I think had any relevance were at the Crossroads shanty town which was being demolished. That's literally when I put my first important roll of film through my first camera. The end of the story was being taken away in a police van. Crossroads was under the threat of bulldozers and you saw a lot of dramatic things happening. I used the photographs in my first portfolio.

I knew soon after that I wanted to be a photographer, but it took a while to get to that point. At that time, I knew very little about photography worldwide. I was aware of [the older South African photo-journalist] David Goldblatt and his work in the copper mines, and I also remember finding a magazine featuring work by Mary Ellen Mark [the American documentary photographer] and Annie Leibovitz's Rolling Stone portraits. I thought I would love to do that!

First, I took a job as a social worker and was working next door to the District 6 neighbourhood which was being demolished. I used to go in there to take case studies - and would take photographs too. I was working with the National Institute for Crime and the Rehabilitation of Offenders and would visit the prisons, people on parole, offenders. That went on for a year then I decided to move to Johannesburg in 1981, and found a job as a photographer's assistant. But on weekends, I freelanced as a press photographer, and joined the Rand Daily Mail. Then I was really in the thick of apartheid South Africa. It was a strange time: I would go from being assigned to cricket and fashion shows to Soweto to cover a family whose child was on Death Row for being a so-called "terrorist".

Although you say you were isolated and your world view was very narrow, by the time you were working in the media - albeit still without television - were you more aware of international photography and the international media's response to the situation in South Africa?

Because of apartheid, culturally, everything was pretty stifled. There was no telly worth watching and one was always aware of the regime keeping an eye on anything controversial or "threatening". I had travelled abroad and as a family we were well read and culturally and politically aware. I remember going for a job as an assistant and another candidate told me my work reminded him of Robert Frank [the pioneering American documentary photographer]. I'd never heard of him - because I didn't study photography at university.

So when did you get out into the wider world?

My last job was being sent by The Star to Sharpeville [site of the 1960 Sharpeville Massacre]. They 'd thrown a cordon around the township and issued a state of emergency, and wouldn't let me inside. After that, I headed to London (it was 1985), and went to study at the London College of Printing. I was picked up by the photo-editor at the Sunday Times and offered work. One of the first shoots I did was a photograph of Lord Lew Grade, and Andrew Neil [then editor of the paper] responded to it and I was offered a full-time job. But then the Wapping saga happened and because I was living in a fairly radical household and was seen as a "scab" for continuing there, I elected to leave. I returned to South Africa for a while and when I came back to London, that's when my freelance life as a photographer in the UK started.

I would guess that the Truth and Lies project - photographing victims and perpetrators during the Truth and Reconciliation hearings in South Africa - will remain your best-known and most significant work. It was an incredibly ambitious project. How did decide to launch it, and how did you manage to establish yourself and the work, in such an emotionally and politically charged and complex situation?

It happened in 1996 when I went back to Cape Town for my sister's wedding. Every Sunday night my parents would discuss a programme called Special Assignment, which was showing the hearings on television. What was unfolding were these extraordinary scenes at the Truth Commission. I absolutely knew that I had to cover it. I came back to London, wrote up a proposal through my agency, Network, and sent it to Kathy Ryan, photo-editor of the New York Times Magazine. Kathy sent me there, and at the same time commissioned me to do a portrait of Mandela for the cover. I landed back in South Africa five months later.

It was up to me to create a structure to make the photographs work. My idea was to photograph victims, perpetrators, heroes, and details. Also, because of my childhood memories of South Africa's light and the stippled walls, I had the idea of photographing almost outside of the hearings. I didn't quite know how but I knew I was going to erect studios around these hearings because I didn't want it to look like typical photo-journalistic work, but to have some kind of drama and be quite epic. I wanted to look into the eyes of these men.

Before I wrote up the proposal, I contacted the makers of the TV programme and got their agreement that I could tag along to some of the hearings. And I wrote to Desmond Tutu asking to become the official Truth and Reconciliation photographer. I didn't get it, but I think that fact allowed me more flexibility.

On the first trip, I covered some very powerful hearings, and I photographed Mandela at the Presidential House. Clearly it was a very emotional experience - even as you discuss it again, all these years later. Yes. Still. I sent the photographs to Kathy Ryan and she sent me back to South Africa. By that point, I knew that I had to continue.

Did anyone refuse to be photographed or create problems for you?

There were stories all the time, but especially with Winnie Mandela. Every time she was booked she would back out, right to the last moment. I photographed her in the hearing but never one-to-one.

How did you cope with working with people who you knew had tortured or killed, and with the actual victims or their relations in the courtroom? Were you able to find complete detachment to be able to continue?

I don't think you have a complete detachment but the camera affords you a visible barrier, and that can buffer the emotion a little bit. I proved that because from being in the hearings - and I attended quite an amount of them - I found it was more raw and tough to handle than if you were in the press room, watching on the monitors. But it did not take away the fact that I would be trembling when I was photographing five perpetrators together because that is a seething mass of brute power and you know that that's why those people were able to do the things they were able to do; operating in packs one can be much more brutal than if you are alone.

One of the images I never ever expected to get was of a victim and a perpetrator in the same frame. But when I was at the trial of Winnie Mandela's football team for murdering the boy called Stompie Seipei, his mother was there. I was on the sidelines where I'd set up a studio. Suddenly Jerry Richardson, the man alleged to have murdered her son, was there in the room too - in handcuffs and carrying a football. She requested to be photographed with him. If you look at her body language, she's turned away. It was such a tough moment. And he's looking inquisitively into the camera, with a pretty gung-ho kind of expression. I don't know if that was his way of begging some kind of forgiveness from her, but it was a very odd thing to do. I just remember the silence as I was taking the photograph.

Did the magazine portraits which you became known for in this country serve as some kind of light relief in between the Truth and Lies sessions?

Yes, I think they really saved me, and also helped me go back there and be fresh. But I love the challenge of portrait work, of depicting people in a way that's novel, different and memorable. When you're working with people who have business and time constraints, it's challenging and demanding and you only have one chance. It's very much like performance: you need to go in, take control, make an impact with first impressions. If you don't connect fairly instantly, it affects the end result.

That's also true in the very different situation where you were photographing people for Truth and Lies - you needed to find some way to connect with them, quickly.

Yes, and that's why, if you're talking about the perpetrators, for me to allow them to know that I was sitting on the other side of the political fence wasn't going to do me any good at all. Lots of people have asked me how I got those photographs and the answer is in the same way that I would use my "charm" or knowledge, or way of winning somebody over [for a celebrity shot]. That's what we do. Time is concertina-ed and you feel it's like a compressed moment and you need to give it everything in that space. I think that's why I rather like the challenge of not having very much time.

We are featuring three specific areas of your work in our Gallery. Truth and Lies, Portraits and Affinities, which documents friendships. What was the inspiration for that?

After I had a bad break-up, I relied a lot on my friends, and started to think about how friendships and relationships come out of creative partnerships. The idea was taken up by the Telegraph Magazine and called "Soul Mates", and it soared. I soon had people researching it for me! I would start with one person - like Willem Dafoe, who worked with Kate Valk at the Wooster Group, then Jeff Koons with the bust of Louis XIV, Allen Ginsberg with the composer Hal Wilner, Damien Hirst and Jay Jopling. And Gilbert and George chose their cleaner, Stainton Forrest. It was a lot of fun!

Your latest project Sangoma is about traditional South African healers, shamans who are the link with the ancestors. The word reminds me of Miriam Makeba's autobiography which she named for her sangoma mother. What was your connection or interest with sangomas, and how has the work proceeded?

It's a work-in-progress! Just after Truth and Lies was published in 2002, I started it, and around the same time, I discovered that I had family and roots in the Ukraine. I started a project using film (my first foray into the medium) of discovering my family. So now I'm combining that with the sangoma, because both are about ancestors, family, migration - quite universal themes. I concentrated on the Sacred Valley on the Lesotho-South African border, where people are summoned by their ancestors. It's a deep-rooted cultural belief. I went quite cynically. On the first day I trekked into the mountain - and I was hooked. People get called to train as healers, and if they don't heed the call, dreadful things can happen to them. So they trek into the valley where they become twasas, or trainee healers, until they are initiated as a sangoma. The process involves sacrifice and traditional beliefs but also extends into Christianity.

Stylistically, this work seems quite traditional and very different from your other series. Also, you shift between black and white and colour, which you hadn't previously done on Truth and Lies, although you do for magazine portraits.

Yes, I think it's quite contemporary. After my first trip, I couldn't not respond to the landscape, it's rugged and very varied, and I found myself documenting the details as well as the people. I think colour is as impactful as black and white, but it depends on how it's treated. There is a way of making colour look contemporary.

If you had shot the Truth and Lies portraits in colour, would their impact be as strong?

I can't give a clear-cut answer. But I do know that when I first saw Claude Lanzmann's colour documentary Shoah about the Holocaust, all I had understood from when I was young and seeing it in black and white was contradicted. And then I realised that it happened in daylight and in colour. I feel, in a sense, with black and white you do take away a little bit of the reality in a medium which is already a departure from reality.

- See three Jillian Edelstein portfolios in theartsdesk gallery.

- Visit Jillian Edelstein's website.

- Buy Jillian Edelstein's Truth and Lies.

- A selection of Jillian Edelstein's portraits are currently on display at Roast, The Floral Hall, Stoney Street, London SE1

Add comment