If your most successful creative collaboration as a couple is that tilting IKEA bookcase, prepare to be shamed: Stephen Gillies and Kate Jones have spent the past 20 years crafting exceptional blown-glass pieces together. The pair studied at Stourbridge College of Art – Stephen glassmaking and Kate fine art – and their work is a result of those complementary skills. You can see some of it next week at the Royal Botanic Gardens’ celebration of craft, Handmade at Kew.

Can you explain the traditional methods you use?

We make glass without moulds, so we free blow the material. It makes the process slow compared with factory production, where the material is blown into moulds to ensure uniformity and increase production numbers. We still blow glass as it was made before the Industrial Revolution, for the sheer love of the process and the material. It's not about numbers – it’s the challenge of crafting each piece as well as we can, by hand. This way of making is about creativity with the material, exploring forms and colours, the myriad possibilities, and the discipline – it’s almost like yoga! We produce a studio collection of small Beautiful Bowls, which also form the basis of large, complex, overlay cameo works.

How long does it take to make a piece, from first idea to completion?

How long does it take to make a piece, from first idea to completion?

Stephen: A unique work takes about a week. First I blow the piece and add colour, which takes over an hour. Lose your concentration for a moment and you’ve lost the piece – there’s no rest or second chances with hot glass. (Stephen pictured right)

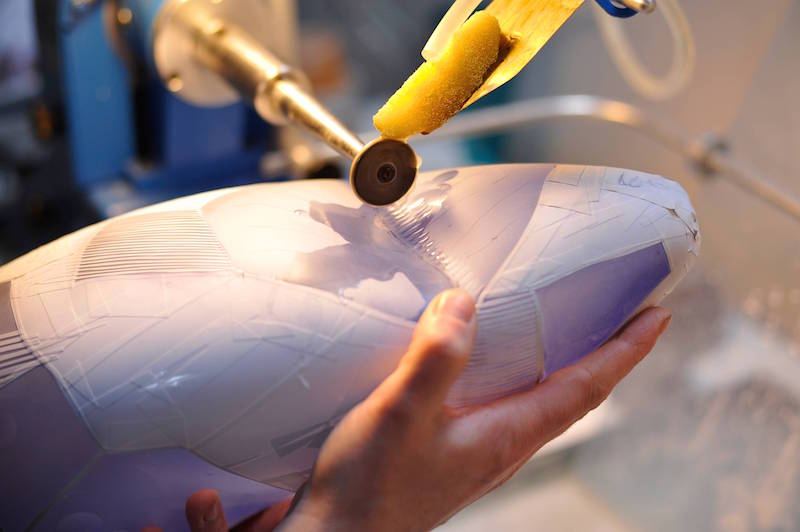

Kate: When the glass is cold, I engrave each piece with the complex marks and remove the colour. I no longer paint, as the contrast between the two media and ways of mark-making was too great. However, drawing is still the foundation of all our work.

What’s it like collaborating with your life partner?

Working together works for us, and has done for over 20 years. We’re not in competition – we have very different skillsets and different ambitions for each piece. It’s not always plain sailing, but when it comes to the work, we know when a piece is right and we always agree on that.

Do you draw on your rural surroundings?

Yes, our location in the heart of the North York Moors is stunning – the changing colours and light are a constant source of inspiration. The landscape here is subject to intensive and contrasting land management, and the harsh northern elements create distinctive marks, patterns and colours from the two areas of high heather moorland and soft, low agricultural dales. The moor wall is the divider between them, and has been the subject of many pieces.

What are some of your favourites?

What are some of your favourites?

Our current work – the “pushed” Landscape Studies (pictured left). Stephen makes a thin-walled, symmetrical, elegant glass bowl. Then, at the very last moment, while it’s still hot, he pushes the rim to distort the form, allowing a change to happen that he’s not fully in control of. This creates soft forms that reflect the lie of the land and make the pieces more of this landscape when engraved.

Our previous series, Aesculus (pictured below), studied the details and universal patterns found within the timeless form of the horse chestnut seed. That’s now in several museum collections, including the V&A. At Kew, we’ll be showing our studio production works, small Beautiful Bowls, Limited Edition bowls engraved with the wild flowers found in our dale, and one or two of our larger, one-off Landscape Studies works.

Who is your greatest influence?

Stephen: I pursued an old-fashioned apprenticeship after studying, and then worked for glassmakers in the UK, Denmark, Switzerland and the USA. The biggest influence on our work was our time with Baldwin Guggisberg in Switzerland and their collaborations with Lino Tagliapietra, as well as being part of Dale Chihuly’s team.

Do any other artists inspire you?

Do any other artists inspire you?

Kate: It’s always good to see the ways in which new technologies are changing the cold processes with glass and to view other makers’ work – in particular, Baldwin Guggisberg and Ann Wolff. I studied painting, and I admire Hitchens, Lanyon and Sutherland. Twitter is a real visual feast – it’s like having a little gallery in your hand! You can see the work of contemporary artists like Malcolm Ashman, Peter Joyce, Peter Esslemont and Andrew Bird.

Is the process you use in danger of dying out?

It feels like studio glassmakers are a bit like hen’s teeth, as the cost of teaching those skills and running a hot glass studio are both monumental. However, there are still clusters of determined makers in the UK and, in particular, the west coast of America. We think there will always be a few who find a way to blow glass. Men and women have been working with glass for over 3,500 years, finding new technologies to allow them to be creative with what is considered by many to be the most demanding of all materials.

We’re also in something of a glass age, as it’s contributing to the speed of development in many forms of technology, such as communications, and in architecture. And the unique qualities of this material are being appreciated by many artists, like Laura and Alessandro Diaz de Santillana, who recently exhibited at Yorkshire Sculpture Park. (Kate cutting glass pictured below)

How do you balance traditional methods with a contemporary aesthetic?

How do you balance traditional methods with a contemporary aesthetic?

Glassmaking takes a certain level of skill if you’re going to realise what you’ve got in your mind or in a sketch in the final form. That skill has a long lineage – the technical knowledge we use can be traced back to Swedish glassworks Orrefors [founded in 1898] via our apprenticeship with Philip Baldwin, who in turn apprenticed with Wilke Adolfsson. The bowl form is as old as time – some say the making of a clay vessel was the catalyst for civilisation itself. We honour that form: it sets the parameters for our work, within which we try to reflect the world around us through glassmaking and engraving. Each finished bowl is an exploration.

- Handmade at Kew at the Royal Botanic Gardens 8-11 October

- Gillies Jones’s handmade blown glass pieces

Read other articles in We Made It, our series on craft in partnership with Bruichladdich

Add comment