Always desperately seeking the next profit-boosting lifeline, the record industry is getting all worked up about the "vinyl revival". While sales of CDs and downloads have been falling, those shiny black circles, once believed defunct, have been enjoying an upward surge. Tesco has even taken the bizarre decision to stock a triple LP by Iron Maiden.

Don't get too excited, though. Vinyl apparently now makes up about three per cent of UK record sales, and while this is clearly an improvement on the 0.1 per cent share vinyl dwindled to in 2007, we're not looking at the imminent death of Spotify and iTunes here.

Anyway, as far as Pete Hutchison of the Electric Recording Company is concerned, all this is beside the point. Hutchison's company specialises in vinyl, but only of the most exquisite and rarefied kind. The Electric Recording Company isn't interested in bashing out a quick vinyl knock-off of some pop or club hit, but instead applies a fanatical connoisseur's dedication to recreating some of the most prestigious recordings of the 1950s and '60s, a period when, as the company's website puts it, "analogue sound recording was in its technological pomp". Hutchison wants to recapture the authentic sound from the original tapes, with no 21st century gloss applied. "This is about hearing how things sounded back then on mint vinyl, with no compromise," he declares.

Anyway, as far as Pete Hutchison of the Electric Recording Company is concerned, all this is beside the point. Hutchison's company specialises in vinyl, but only of the most exquisite and rarefied kind. The Electric Recording Company isn't interested in bashing out a quick vinyl knock-off of some pop or club hit, but instead applies a fanatical connoisseur's dedication to recreating some of the most prestigious recordings of the 1950s and '60s, a period when, as the company's website puts it, "analogue sound recording was in its technological pomp". Hutchison wants to recapture the authentic sound from the original tapes, with no 21st century gloss applied. "This is about hearing how things sounded back then on mint vinyl, with no compromise," he declares.

So far, Electric has been focusing on classical music, and among its carefully-curated titles are Janos Starker's 1959 recording of Bach's solo cello suites, Schubert's works for violin and piano recorded in 1954 by Johanna Martzy and Jean Antonietti, and the Beethoven and Tchaikovsky violin concertos by the great Russian fiddler Leonid Kogan. These will cost you £300 to £400 a copy, if you can get one – Hutchison leaks his releases out at five copies per month, only manufactures 300 copies of a particular album, and frequently sees every one snapped up before the official launch date (often by buyers from China and the Far East). But bear in mind that you could expect to pay 10 times as much for an original LP of the same material made in the Fifties or Sixties.

Digital is like a microwaved meal from Tesco and analogue is like real food

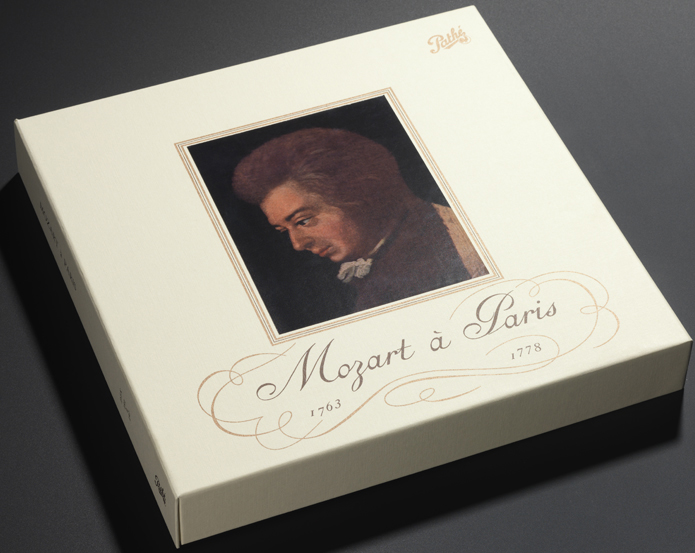

"Our Mozart à Paris set [a seven-disc rarity originally released on French Pathé in 1956, pictured above] would be £10-£12,000 in mint condition from a dealer," he reports. "I wanted to get the original tapes, remake the records using all the original equipment from the 1950s which I had restored over a long period, use original printing techniques and recreate the record as it was, so that I could have that record in mint condition at home. Then the hope is that other people would want that record."

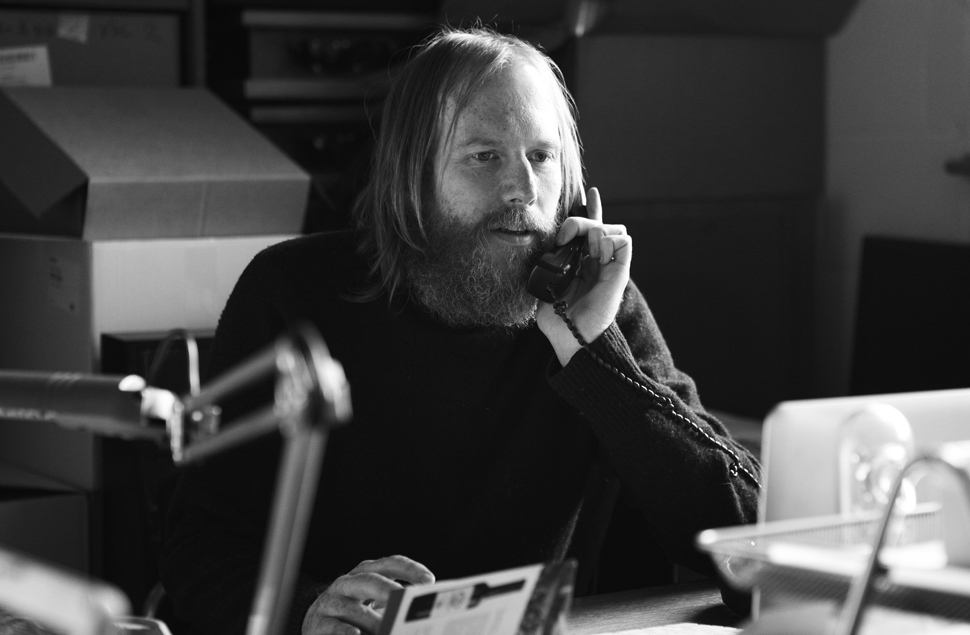

Hutchison, whose bohemian hirsuteness makes him resemble a refugee from the golden age of English psychedelia, has been able to fund this über-niche venture thanks to the success of his label Peacefrog, which was formed in 1991 and whose artists cover a variety of electronic, folk and indie styles. It has enjoyed conspicuous success with José González and Charlene Soraia (who have both had their music used in major TV advertising campaigns), Little Dragon and French cover version specialists Nouvelle Vague. He caught the classical bug after his father died some 15 years ago, and left Pete his classical record collection.

"They were Sixties records, mainly bought when my dad lived in New York but on the American EMI imprints or Decca imprints," he recalls. "They weren't the super-rare records, because the super-rare ones are the English first pressings. I started collecting the first pressings of these records by the Fifties and Sixties classical performers, then found myself getting into quite deep water in terms of my expenditure."

Reconstructing these historic discs from scratch has proved such a lengthy and expensive process that he'll be lucky to turn a profit in this lifetime. He went in search of 1950s valve-powered mastering and vinyl-cutting equipment, even tracking some of it down in Romania. At the Electric Recording Company HQ nestling up against the concrete pillars and roaring traffic of London's Westway, he proudly shows off the massive cutting machine built by Lyrec of Copenhagen ("it would have cost roughly the price of an average house, and weighs about a ton"), a Neumann lathe made of aluminium, and an EMI reel-to-reel valve tape recorder which was used at Abbey Road studios in the 1950s. Hutchison found an invaluable ally in Sean Davies, a sometime Decca recording engineer with an encyclopedic knowledge of vintage sound equipment. Helpfully, he has his own private stash of valves, antique components and original technical manuals.

Reconstructing these historic discs from scratch has proved such a lengthy and expensive process that he'll be lucky to turn a profit in this lifetime. He went in search of 1950s valve-powered mastering and vinyl-cutting equipment, even tracking some of it down in Romania. At the Electric Recording Company HQ nestling up against the concrete pillars and roaring traffic of London's Westway, he proudly shows off the massive cutting machine built by Lyrec of Copenhagen ("it would have cost roughly the price of an average house, and weighs about a ton"), a Neumann lathe made of aluminium, and an EMI reel-to-reel valve tape recorder which was used at Abbey Road studios in the 1950s. Hutchison found an invaluable ally in Sean Davies, a sometime Decca recording engineer with an encyclopedic knowledge of vintage sound equipment. Helpfully, he has his own private stash of valves, antique components and original technical manuals.

Hutchison has destroyed numerous vinyl lacquers (from which subsequent pressings are made) and several complete pressing runs which failed to meet his exacting standards, but even when the audio results are deemed acceptable there remains the almost equally complex issue of creating the record sleeves. He works on these with the specialist printers Hand & Eye Letterpress in Whitechapel, and seems to take an almost masochistic delight in finding fresh minutiae to lose sleep over. Several releases feature an image of a tasselled rope on the sleeve (a design motif favoured by EMI, from whom Electric acquired rights to the original tapes), but this has proved exasperatingly difficult to replicate.

"I was never happy with the tassel," Hutchison frets. "We're doing a Johanna Martzy Schubert release which has got the same tassel, so we're revisiting how to get it looking better (Johanna Martzy pictured left). We've done about five different versions and in the end we got a letterpressed image, and we got the metal plates made and so on. After three or four goes we got something I was happy with, though we noticed that the image looked as if it was made up of dots even though it's not a digital process. Anyway, we've gone with that and it is of the period and I think it looks right."

"I was never happy with the tassel," Hutchison frets. "We're doing a Johanna Martzy Schubert release which has got the same tassel, so we're revisiting how to get it looking better (Johanna Martzy pictured left). We've done about five different versions and in the end we got a letterpressed image, and we got the metal plates made and so on. After three or four goes we got something I was happy with, though we noticed that the image looked as if it was made up of dots even though it's not a digital process. Anyway, we've gone with that and it is of the period and I think it looks right."

He's about to take an evolutionary leap by branching out into vintage jazz LPs. He's starting off with the hard-bopping Tommy Flanagan Trio Overseas (1957) and Elmo Hope's Informal Jazz (1956), the latter featuring trumpeter Donald Byrd and saxophonists John Coltrane and Hank Mobley. Mobley's own album Mobley's Message will follow in due course. All of these are from Bob Weinstock's renowned Prestige label, and Hutchison was pleasantly surprised when the label (now owned by Concorde Music Group) were happy to send the original master tapes over from Los Angeles (Pete Hutchison, below). Hutchison plays some samples over his studio speakers, Flanagan's piano skittering over high-kicking grooves from drummer Elvin Jones and bassist Wilbur Little, then Hope leading his troupe through a warm and languid take of "Polka Dots and Moonbeams". Coltrane's tenor sax floods the room with an almost overwhelming physical presence, as if the man himself was standing there blowing. Typically, Hutchison has tracked down the same recording equipment used by fabled jazz recording engineer Rudy Van Gelder, who worked with everybody (Miles Davis, Thelonious Monk, Wayne Shorter, Sonny Rollins...). Thus, these jazz discs will be created using a Scully lathe (its motor having been rewound to work with UK mains voltage) and Gotham cutting amplifiers.

Hutchison plays some samples over his studio speakers, Flanagan's piano skittering over high-kicking grooves from drummer Elvin Jones and bassist Wilbur Little, then Hope leading his troupe through a warm and languid take of "Polka Dots and Moonbeams". Coltrane's tenor sax floods the room with an almost overwhelming physical presence, as if the man himself was standing there blowing. Typically, Hutchison has tracked down the same recording equipment used by fabled jazz recording engineer Rudy Van Gelder, who worked with everybody (Miles Davis, Thelonious Monk, Wayne Shorter, Sonny Rollins...). Thus, these jazz discs will be created using a Scully lathe (its motor having been rewound to work with UK mains voltage) and Gotham cutting amplifiers.

And once again, the cover artwork is causing much chin-stroking. Hand & Eye didn't have the exact American typeface originally used by Prestige, so a set of type had to be sent over from Canada at wallet-emptying expense. Meanwhile, the particular authentic method of making the sleeves using paper folded over board has had to be perfected with the aid of "a guy who makes a lot of sleeves in his garden shed in Dartford". Then Hutchison was perturbed to find that the high-quality white paper he was using was too white – whiter than the original Prestige sleeves.

But perhaps this was because those sleeves had yellowed with age? "That was my original thought," mutters Hutchison, "but on the front cover of the Tommy Flanagan album you can see the paper underneath and it's laminated on top, and lamination normally protects colour. So it's laminated and off-white, which leads me to believe that maybe it wouldn't have been pure white. But that probably doesn't mean they deliberately did that, it probably means they used an inferior grade of paper" (Hank Mobley, below).

He has been obsessing over all this for months, like a mixture of detective, antiquarian and Gil Grissom from CSI. It would drive most people nuts, but it seems to fill him with mysterious energy. Partly it's the music which drives him, but it's also a quest for something precious but intangible which he fears is being lost.

He has been obsessing over all this for months, like a mixture of detective, antiquarian and Gil Grissom from CSI. It would drive most people nuts, but it seems to fill him with mysterious energy. Partly it's the music which drives him, but it's also a quest for something precious but intangible which he fears is being lost.

"I'm talking generally about digital versus analogue. Digital is like a microwaved meal from Tesco and analogue is like real food. What we're doing here is the top end of that in the analogue domain, which is the organic food, the three Michelin stars food. People like the convenience of MP3s, but with CD things started sounding harsher and generally not as pleasant and musical, and MP3 is a compressed version of that, so it's the worst possible thing you could be listening to.

"Some people are willing to spend a bit more money and time buying these records, relaxing, enjoying the sound in a kind of meditative way, seeing it as a way of escaping from all this fast sharing of technology and the whole fast information world. If Beethoven had been given a mobile phone and a Gameboy, would he have written anything? People moan about music nowadays being pastiche, and it's going to get worse because nobody's got any time to think. So this is my stand against that. This is me saying this is when music was good, this is when it was at its best."

Read other articles in We Made It, our series on craft in partnership with Bruichladdich

Add comment