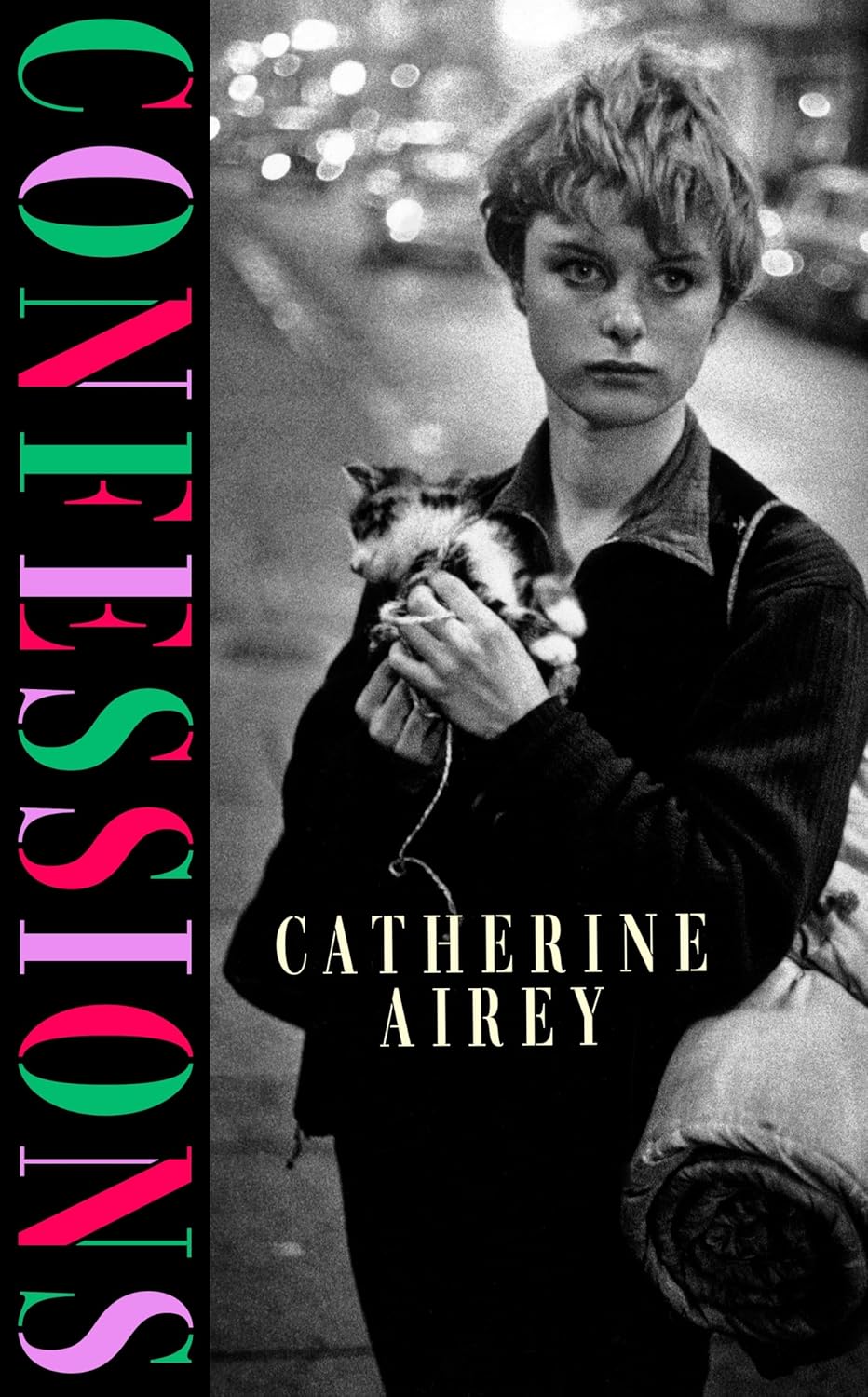

Anglo-Irish author Catherine Airey’s first novel, Confessions, is a puzzle, a game of family secrets played through the generations. Set partly in New York and partly in a small town in Donegal, the book moves back and forth through time and space becoming, in the process, a compulsive read: a fascinating Russian nesting doll of family trauma.

There are obvious cliches in the familial "saga" genre, which at times can make the book feel a little artificial, but it’s nonetheless a fascinating, often heartbreaking tale. We open with the traumatic loss of the Cora’s father in the chaos of 9/11. Cora is left lost and alone, wandering around a scarred New York. She is the first of four women that the book follows, each affected by the radiating pain of the generation before her. Cora seems dissociated, disconnected from the reality of the death of her father and before that, of her mother by suicide. The only lifeline she has is a connection with an aunt, Róisín, who she had never met before. As Cora travels to Ireland, to the little town of Burtonport, to live with her, the narrative flips to Róisín in 1974 – the first of several changes.

Each time the story moves back and forth between characters, there are smaller and larger accretions, both of information and of repetitions. There are patterns, mirrors, and twinnings throughout the novel, introduced on the first page, which is set up like an early computer game, one in which a command was inputted in order to move the story along. We are introduced to two sisters, entering a boarding school in Burtonport itself, a site which becomes central to the story of Confessions. However, nothing is certain in the novel: there are small moments of strangeness that disrupt our sense of things. For instance, Cora’s mother, Máire, buys a second-hand coat in New York as a student; she finds note in the pocket that reads: “‘she herself is a haunted house,” which calls back to the haunted house featured in the computer game. That is, the borders between people and their landscape dissolve, the spaces in which they live and are written becomes intimately confused, leaving the reader questioning the truth of what we read. This eerie feeling of disconnection is compounded by the book’s grammatical moves: the telling of Máire’s story, for example, plays out in the second person: a closeness offered but not given, always at one slightly distant remove.

Each time the story moves back and forth between characters, there are smaller and larger accretions, both of information and of repetitions. There are patterns, mirrors, and twinnings throughout the novel, introduced on the first page, which is set up like an early computer game, one in which a command was inputted in order to move the story along. We are introduced to two sisters, entering a boarding school in Burtonport itself, a site which becomes central to the story of Confessions. However, nothing is certain in the novel: there are small moments of strangeness that disrupt our sense of things. For instance, Cora’s mother, Máire, buys a second-hand coat in New York as a student; she finds note in the pocket that reads: “‘she herself is a haunted house,” which calls back to the haunted house featured in the computer game. That is, the borders between people and their landscape dissolve, the spaces in which they live and are written becomes intimately confused, leaving the reader questioning the truth of what we read. This eerie feeling of disconnection is compounded by the book’s grammatical moves: the telling of Máire’s story, for example, plays out in the second person: a closeness offered but not given, always at one slightly distant remove.

This is worked with and confounded by the book’s various patternings, like the tattoos of puzzle and game pieces that show up on various characters, the presence of the twin towers, alongside more irreverent objects like the humble Twix. Each woman who appears in Confessions (a novel where men appear, seemingly, only to disappoint), is a slightly-rewritten version of the others we’ve previously encountered. Máire seems to split apart in imperfect mitosis, like the two sisters of the game, generating quasi-clones: her sister, Róisín, possesses the calm she lacks; Laura is another artist; her friend Franny, rich and lonely, causes an inadvertent fracture in Máire’s life; Isabelle’s father died in such a similar way to hers; Cora, her own daughter, walks the same paths, and often makes the same mistakes. Róisín describes this claustrophobia at one point: “But if I ever decided to do anything without her, to claim some sense of self? That would make her go beserk. She was the only one allowed to change. I was supposed to stay the same”.

This gathering, weird repetitiousness can at points make Confessions feel a little too laboured, coming to a head in perhaps too obvious coincidences. However, the slight surreality and the theme of recurrent trauma are also the novel’s driving force, a game needing to be played over and over again with different commands entered until the puzzle is solved. As Róisín says: “The thing I liked about video game writing was that you got to think through other scenarios, imagine how things might have ended up if certain things had gone a different way.”

Add comment