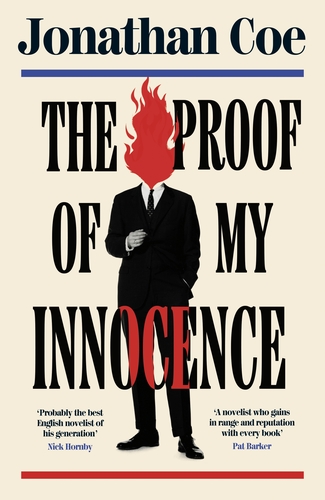

Jonathan Coe: The Proof of My Innocence review - a whodunnit with a difference | reviews, news & interviews

Jonathan Coe: The Proof of My Innocence review - a whodunnit with a difference

Jonathan Coe: The Proof of My Innocence review - a whodunnit with a difference

Political satire, social observation and literary artifice elevate this ostensibly 'cosy crime' caper

Anyone who has been on a British train in the last ten years will have been irritated to distraction by the inane and ubiquitous “See it, say it, sorted” announcement that punctuates every journey, but only Jonathan Coe has channelled that annoyance into literary form.

A satire on contemporary Britain, an analysis of the political tectonics of the last 40 years, a thoughtful meditation on why writers write – The Proof of My Innocence is all these things, but its starting point is a howl of rage about the fact we can’t just enjoy a quiet train journey any more.

Coe operates partly through pastiche. The central conceit is of a “cosy crime” thriller centred around a murder at a country-house hotel, and there are also sections set out as a sub-David Lodge “campus novel” and “autofiction”, a form in which writers chisel narrative from the actual events of their lives. But being Jonathan Coe, these are all woven together with an elaborate knowingness, a gleeful postmodernism that rescues things whenever the plot – or should I say “the plot” – gets a bit bogged down. It is plotted with Coe’s usual painstaking care, and if the coincidences sometimes feel a bit too pat, and obstacles a bit too easily overcome, his get-out-of-jail-free card is the “meta” conceit behind the whole thing.

So, what is the story? It begins with young woman, Phyl, who has graduated from university and is now chopping sushi at Heathrow airport, but dreams of being a writer. But of what kind of book? She thinks of “cosy crime” – the cutesy-murderous world of Richard Coles and Richard Osman – and is instantly thrown into the middle of such a story. Her mother’s friend Christopher meets a grizzly end at a right-wing political conference at Wetherby Hall, with the resolution of the case taking us back to 1980s Cambridge and to a denouement in modern-day Venice. It is all set against the backdrop of the Liz Truss’s brief Prime Ministership, and the death of the Queen.

There’s a big old twist (of course there is!), clues aplenty, and the mystery is, on one level, wrapped up, as it must be by the “cosy crime” rules of engagement. But on another level plenty is unresolved, not least the question of what is real anyway. As one character says, surely ventriloquising the author’s own opinion: “How do you write the truth?… In a world where all efforts to tell the truth in words or images are compromised, contaminated, there’s something unique about fiction. Something authentic, something you can depend on.” This is Coe in defence of not just this book but his whole life’s work, which he clearly feels is under question. For all its irony, its tricksiness, its surface light-heartedness, The Proof of My Innocence is a novel earnestly using fiction as a way of telling the truth.

There’s a big old twist (of course there is!), clues aplenty, and the mystery is, on one level, wrapped up, as it must be by the “cosy crime” rules of engagement. But on another level plenty is unresolved, not least the question of what is real anyway. As one character says, surely ventriloquising the author’s own opinion: “How do you write the truth?… In a world where all efforts to tell the truth in words or images are compromised, contaminated, there’s something unique about fiction. Something authentic, something you can depend on.” This is Coe in defence of not just this book but his whole life’s work, which he clearly feels is under question. For all its irony, its tricksiness, its surface light-heartedness, The Proof of My Innocence is a novel earnestly using fiction as a way of telling the truth.

There is lots of contemporary life crammed in – Wordle, EarPods, Netflix – and Coe is refreshing in not ignoring Covid, which so much fiction, on page or screen, simply erases. Sometimes there is a feel of ticking off zeitgeisty features for the sake of it – one of the characters belongs to the “asexual community” for no particularly good reason – but the use of the sitcom Friends by young people as a psychological crutch is well-handled. An example of “anemoia”, a term for “nostalgia for a time before you were born”, it starts out merely as an observation of Gen Z and “Friends discourse” but develops a much wider resonance, in both plot and philosophical terms.

Sometimes the satire is a bit route one (a pub in this Trussian period called the Fresh Lettuce? Too much) and the brushstrokes too broad (such as the fates of the historical Earls of Wetherby). And sometimes the characters become straightforward mouthpieces for Coe’s polemic. But these often hit the bullseye, such as when a young woman talks about “how angry the older generation seemed… For forty years the country’s been shaped in their image and now they look around and they don’t even like what they see.” Trump is never mentioned in the book, but in some ways he is at its heart.

All readers have their bugbears, and Coe offers two examples of mine in the space of 15 pages: characters who say “I’m [Name], by the way”, a formulation I have literally never heard in real life. But for the most part The Proof of My Innocence is deliciously readable, and you feel in safe authorial hands. In the final pages I surrendered to a master puppeteer drawing all the strings together, but never with the “neat, tidy solutions” Phyl starts out wanting, but in a way that is much more ambiguous, unsettling but also uplifting.

- The Proof of My Innocence by Jonathan Coe (Penguin, £20)

- More book reviews on theartsdesk

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Books

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

Thomas Pynchon - Shadow Ticket review - pulp diction

Thomas Pynchon's latest (and possibly last) book is fun - for a while

Thomas Pynchon - Shadow Ticket review - pulp diction

Thomas Pynchon's latest (and possibly last) book is fun - for a while

Justin Lewis: Into the Groove review - fun and fact-filled trip through Eighties pop

Month by month journey through a decade gives insights into ordinary people’s lives

Justin Lewis: Into the Groove review - fun and fact-filled trip through Eighties pop

Month by month journey through a decade gives insights into ordinary people’s lives

Joanna Pocock: Greyhound review - on the road again

A writer retraces her steps to furrow a deeper path through modern America

Joanna Pocock: Greyhound review - on the road again

A writer retraces her steps to furrow a deeper path through modern America

Mark Hussey: Mrs Dalloway - Biography of a Novel review - echoes across crises

On the centenary of the work's publication an insightful book shows its prescience

Mark Hussey: Mrs Dalloway - Biography of a Novel review - echoes across crises

On the centenary of the work's publication an insightful book shows its prescience

Frances Wilson: Electric Spark - The Enigma of Muriel Spark review - the matter of fact

Frances Wilson employs her full artistic power to keep pace with Spark’s fantastic and fugitive life

Frances Wilson: Electric Spark - The Enigma of Muriel Spark review - the matter of fact

Frances Wilson employs her full artistic power to keep pace with Spark’s fantastic and fugitive life

Elizabeth Alker: Everything We Do is Music review - Prokofiev goes pop

A compelling journey into a surprising musical kinship

Elizabeth Alker: Everything We Do is Music review - Prokofiev goes pop

A compelling journey into a surprising musical kinship

Natalia Ginzburg: The City and the House review - a dying art

Dick Davis renders this analogue love-letter in polyphonic English

Natalia Ginzburg: The City and the House review - a dying art

Dick Davis renders this analogue love-letter in polyphonic English

Tom Raworth: Cancer review - truthfulness

A 'lost' book reconfirms Raworth’s legacy as one of the great lyric poets

Tom Raworth: Cancer review - truthfulness

A 'lost' book reconfirms Raworth’s legacy as one of the great lyric poets

Ian Leslie: John and Paul - A Love Story in Songs review - help!

Ian Leslie loses himself in amateur psychology, and fatally misreads The Beatles

Ian Leslie: John and Paul - A Love Story in Songs review - help!

Ian Leslie loses himself in amateur psychology, and fatally misreads The Beatles

Samuel Arbesman: The Magic of Code review - the spark ages

A wide-eyed take on our digital world can’t quite dispel the dangers

Samuel Arbesman: The Magic of Code review - the spark ages

A wide-eyed take on our digital world can’t quite dispel the dangers

Zsuzsanna Gahse: Mountainish review - seeking refuge

Notes on danger and dialogue in the shadow of the Swiss Alps

Zsuzsanna Gahse: Mountainish review - seeking refuge

Notes on danger and dialogue in the shadow of the Swiss Alps

Add comment