Extract: Pariah Genius by Iain Sinclair | reviews, news & interviews

Extract: Pariah Genius by Iain Sinclair

Extract: Pariah Genius by Iain Sinclair

A form-defying writer explores the troubled mindscape of a Soho photographer

Iain Sinclair is a writer, film-maker, and psychogeographer extraordinaire. He began his career in the poetic avant-garde of the Sixties and Seventies, alongisde the likes of Ed Dorn and J. H. Prynne, but his work resists easy categorisation at every turn. Reality shudders against and into its incarnation as fiction; documentary is riddled with the imagination’s brilliant glare; genre-bounds are ruinously questioned.

He has written, for instance, a grotesque account of Thatcherism in Downriver (1991), walked within John Clare from asylum to home in Edge of the Orison (2005), and, in Ghost Milk, exposed the backdoor militarisation of London during the 2012 Olympics. They are diverse books, but they each retain a repeated impetus: to reclaim place and time through a practice of radical imaginative sympathy.

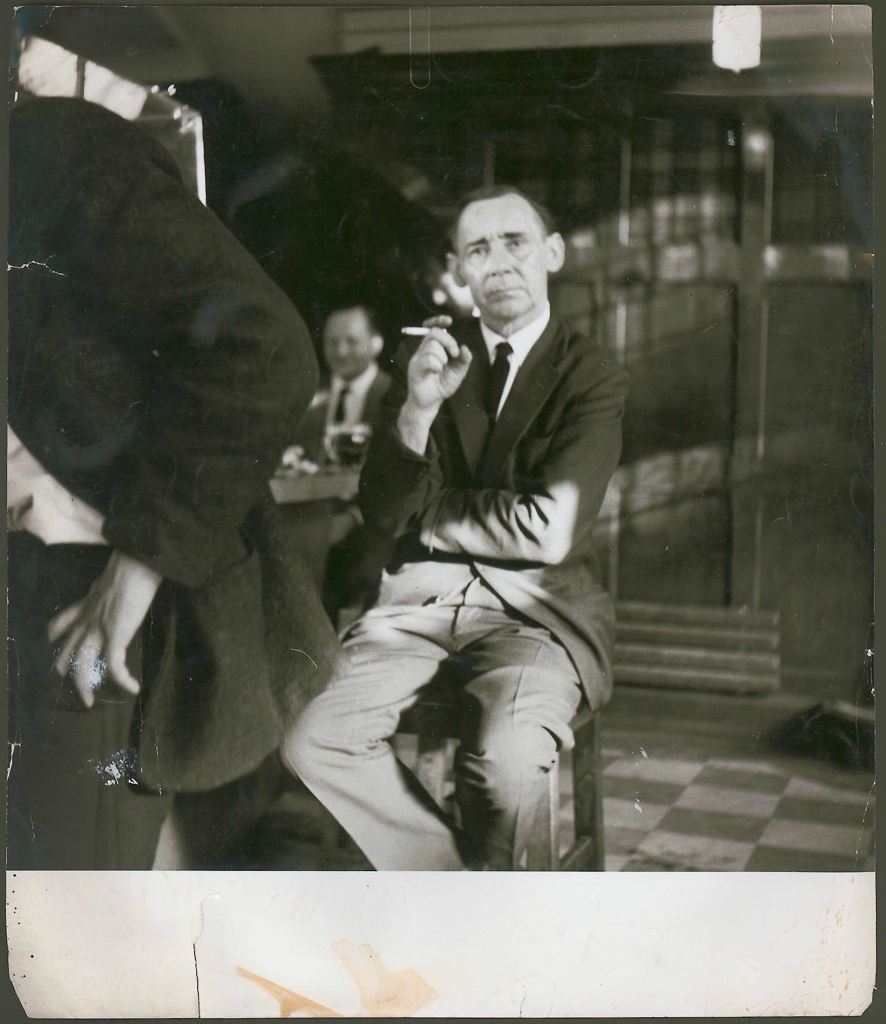

One such place is London. In his latest book, Pariah Genius, Sinclair inhabits – fractiously – the mind of photographer John Deakin, whose images of life in Francis Bacon’s Soho have left a persistent burn on the cultural retina. Whether we know it or not, much of our understanding of Bacon and his friends has been rendered through Deakin’s lens – Sinclair takes on its refracted light in a text of worldly dirt and lyricism.

In the aftermath of Brexit and midst of Covid, the extract below describes the various difficulties of reckoning with Deakin’s existence: how he lived, what he left behind, and the ways in which he may explain or explode a certain strain of complex British history.

***

In the depths of the third Covid-19 lockdown, when London was in brain-dead hibernation, and all projects launched before this time were suspended or abandoned, the messenger from Arnold Circus came to my Hackney door with two enormous yellow boxes. Like cardboard coffins on special offer from Ikea. The boxes contained seventeen albums of John Deakin’s photographs, fresh prints made from recovered negatives and contact sheets; a substantial history of his labours, a flickbook parade of the stunned and waxy faces of his place and time. This momentous gift, a short-term loan, was both a blessing and a curse. I had to extract life – and a measure of coherence – out of these beautifully presented retrievals. They were not the physical materials handled by the artist, handled and junked. But glossed and preserved artefacts lifted out of the recent past and asked to explain themselves. No Deakin DNA, no psychic contamination. The Soho photographer, always alert, skewed and swaying, pre-drunk, post-drunk, pretend-drunk, had landed me, at one remove, with the resurrected eidolons of a story that was his to tell. And only his. A story in pictures. A story he preferred to bury. This was his last joke, after naming Francis Bacon as next of kin, and ensuring that the hermit of Reece Mews would have to make a dire trip to Brighton to acknowledge a corpse.

The delivery of albums felt a legal obligation out of a Victorian novel. Unappeased voices were screaming out of the hairballs and cobwebs of the photographer’s last perch in Berwick Street. And from the layered, paint-spattered filth on the floor of Bacon’s studio. His retreat. His mancave. Now shipped to Dublin.

We inhabit an amnesiac era when the past has to be constantly re- branded. Re-curated. Redacted and improved. Arnold Circus, on the cusp of Shoreditch, had a noble pedigree. Out of extreme poverty – the poster venue for historic blight – came solid municipal dwellings, built to be occupied by obedient families in regular employment. And came too, within a hundred years, a bucolic oasis noticed and celebrated by Patrick Keiller: a site of transcendent stillness and meditation, of listening. At the cinema’s golden hour, when leaves take flame, the Circus claimed its place among the three pilgrimages of Keiller’s influential 1994 film London. The bandstand mound, with its ambulatory paths, its Panopticon summit offering views down seven roads, is a borderland between past and future, between remembered horrors and coming dread. A modestly rewilded toy town replica of Pieter Bruegel the Elder’s Tower of Babel.

We inhabit an amnesiac era when the past has to be constantly re- branded. Re-curated. Redacted and improved. Arnold Circus, on the cusp of Shoreditch, had a noble pedigree. Out of extreme poverty – the poster venue for historic blight – came solid municipal dwellings, built to be occupied by obedient families in regular employment. And came too, within a hundred years, a bucolic oasis noticed and celebrated by Patrick Keiller: a site of transcendent stillness and meditation, of listening. At the cinema’s golden hour, when leaves take flame, the Circus claimed its place among the three pilgrimages of Keiller’s influential 1994 film London. The bandstand mound, with its ambulatory paths, its Panopticon summit offering views down seven roads, is a borderland between past and future, between remembered horrors and coming dread. A modestly rewilded toy town replica of Pieter Bruegel the Elder’s Tower of Babel.

Dappled in dancing shadows from established plane trees, and lavished with birdsong, the Circus solicits movement: the impulse to circle, postponing a slow release of breath, before taking measure of what it means to live on ground where ‘deep topography’ has not yet been extinguished. Arnold Circus invites the overlap of many languages, not as a signature of alienation, but as a human resource. Migrants pause in their migrations. In shady courtyards, observed from open windows, children of different ethnicities play among the conceptual plantings of their triumphantly realised locality.

At the time of the Olympics in 2012, as if to escape noise and fuss, the great London painter Leon Kossoff came here from suburban migration, back to his childhood landscape, the family baker’s shop, in order to make a series of elegiac perambulations. To sketch. To catch at fleeting impressions, where he no longer had the strength to undertake large-scale oil paintings. He left his equipment overnight in what had once been the neighbourhood school.

I knew that Boundary Estate school, Rochelle, from Sunday mornings in the 1970s. I recognised the way that a solid redbrick structure complemented the blocks of improved late-Victorian tenements. Starting early, I made my way to Cheshire Street, to scavenge for unsuspecting books. All the trophies of a vanishing world, barely sorted and displayed for negotiated sale, seemed to be within tantalising reach. For four or five fortunate years there were sufficient finds to keep hope alive, to fill my sacks. And my Camden Passage bookstall. The shelves never grew lighter no matter how many volumes I shifted. A heritage of uncatalogued lumber for someone else to clear. When, out of nowhere, the hour came.

I knew that Boundary Estate school, Rochelle, from Sunday mornings in the 1970s. I recognised the way that a solid redbrick structure complemented the blocks of improved late-Victorian tenements. Starting early, I made my way to Cheshire Street, to scavenge for unsuspecting books. All the trophies of a vanishing world, barely sorted and displayed for negotiated sale, seemed to be within tantalising reach. For four or five fortunate years there were sufficient finds to keep hope alive, to fill my sacks. And my Camden Passage bookstall. The shelves never grew lighter no matter how many volumes I shifted. A heritage of uncatalogued lumber for someone else to clear. When, out of nowhere, the hour came.

The Shoreditch demographic adapted as the rage and ruckus of tribal race wars faded. Premature Brexiteers with shaven heads, and revivalist Mosleyites tapping into echoes of hate crime, confronted slogan-emblazoned righteous opponents, defenders of diversity, at the head of Brick Lane, before retreating into Essex. There were deaths. There were petrol bombs for emerging convenience stores. Outrage and physical challenge morphed into property speculation, style tourism and communal weekend derangement. Deakin’s dungeons, and private clubs where it was always the yellow hour, started to leak out from Soho into Shoreditch. Laughing gas in parks, glittering silver cylinders dressing gutters. White powder in revamped tea warehouses now occupied by dedicated bohemians and trustafarians. It was the twilight of art slackers and genius retailers. And the art colonised the walls.

All I know is that place dictates the story. The petty interventions of humans are of no account. We raid the past to make the present bearable. But there is no present. Just images, scratches, blood colours. Chalk, oil, aerosol: legacy. And outliers to record it.

- This is an exclusive extract from Pariah Genius by Iain Sinclair (CHEERIO, £19.99)

- More book reviews on theartsdesk

Explore topics

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Books

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

Justin Lewis: Into the Groove review - fun and fact-filled trip through Eighties pop

Month by month journey through a decade gives insights into ordinary people’s lives

Justin Lewis: Into the Groove review - fun and fact-filled trip through Eighties pop

Month by month journey through a decade gives insights into ordinary people’s lives

Joanna Pocock: Greyhound review - on the road again

A writer retraces her steps to furrow a deeper path through modern America

Joanna Pocock: Greyhound review - on the road again

A writer retraces her steps to furrow a deeper path through modern America

Mark Hussey: Mrs Dalloway - Biography of a Novel review - echoes across crises

On the centenary of the work's publication an insightful book shows its prescience

Mark Hussey: Mrs Dalloway - Biography of a Novel review - echoes across crises

On the centenary of the work's publication an insightful book shows its prescience

Frances Wilson: Electric Spark - The Enigma of Muriel Spark review - the matter of fact

Frances Wilson employs her full artistic power to keep pace with Spark’s fantastic and fugitive life

Frances Wilson: Electric Spark - The Enigma of Muriel Spark review - the matter of fact

Frances Wilson employs her full artistic power to keep pace with Spark’s fantastic and fugitive life

Elizabeth Alker: Everything We Do is Music review - Prokofiev goes pop

A compelling journey into a surprising musical kinship

Elizabeth Alker: Everything We Do is Music review - Prokofiev goes pop

A compelling journey into a surprising musical kinship

Natalia Ginzburg: The City and the House review - a dying art

Dick Davis renders this analogue love-letter in polyphonic English

Natalia Ginzburg: The City and the House review - a dying art

Dick Davis renders this analogue love-letter in polyphonic English

Tom Raworth: Cancer review - truthfulness

A 'lost' book reconfirms Raworth’s legacy as one of the great lyric poets

Tom Raworth: Cancer review - truthfulness

A 'lost' book reconfirms Raworth’s legacy as one of the great lyric poets

Ian Leslie: John and Paul - A Love Story in Songs review - help!

Ian Leslie loses himself in amateur psychology, and fatally misreads The Beatles

Ian Leslie: John and Paul - A Love Story in Songs review - help!

Ian Leslie loses himself in amateur psychology, and fatally misreads The Beatles

Samuel Arbesman: The Magic of Code review - the spark ages

A wide-eyed take on our digital world can’t quite dispel the dangers

Samuel Arbesman: The Magic of Code review - the spark ages

A wide-eyed take on our digital world can’t quite dispel the dangers

Zsuzsanna Gahse: Mountainish review - seeking refuge

Notes on danger and dialogue in the shadow of the Swiss Alps

Zsuzsanna Gahse: Mountainish review - seeking refuge

Notes on danger and dialogue in the shadow of the Swiss Alps

Patrick McGilligan: Woody Allen - A Travesty of a Mockery of a Sham review - New York stories

Fair-minded Woody Allen biography covers all bases

Patrick McGilligan: Woody Allen - A Travesty of a Mockery of a Sham review - New York stories

Fair-minded Woody Allen biography covers all bases

Add comment