Hugo Rifkind: Rabbits review - 31 wild parties and a funeral | reviews, news & interviews

Hugo Rifkind: Rabbits review - 31 wild parties and a funeral

Hugo Rifkind: Rabbits review - 31 wild parties and a funeral

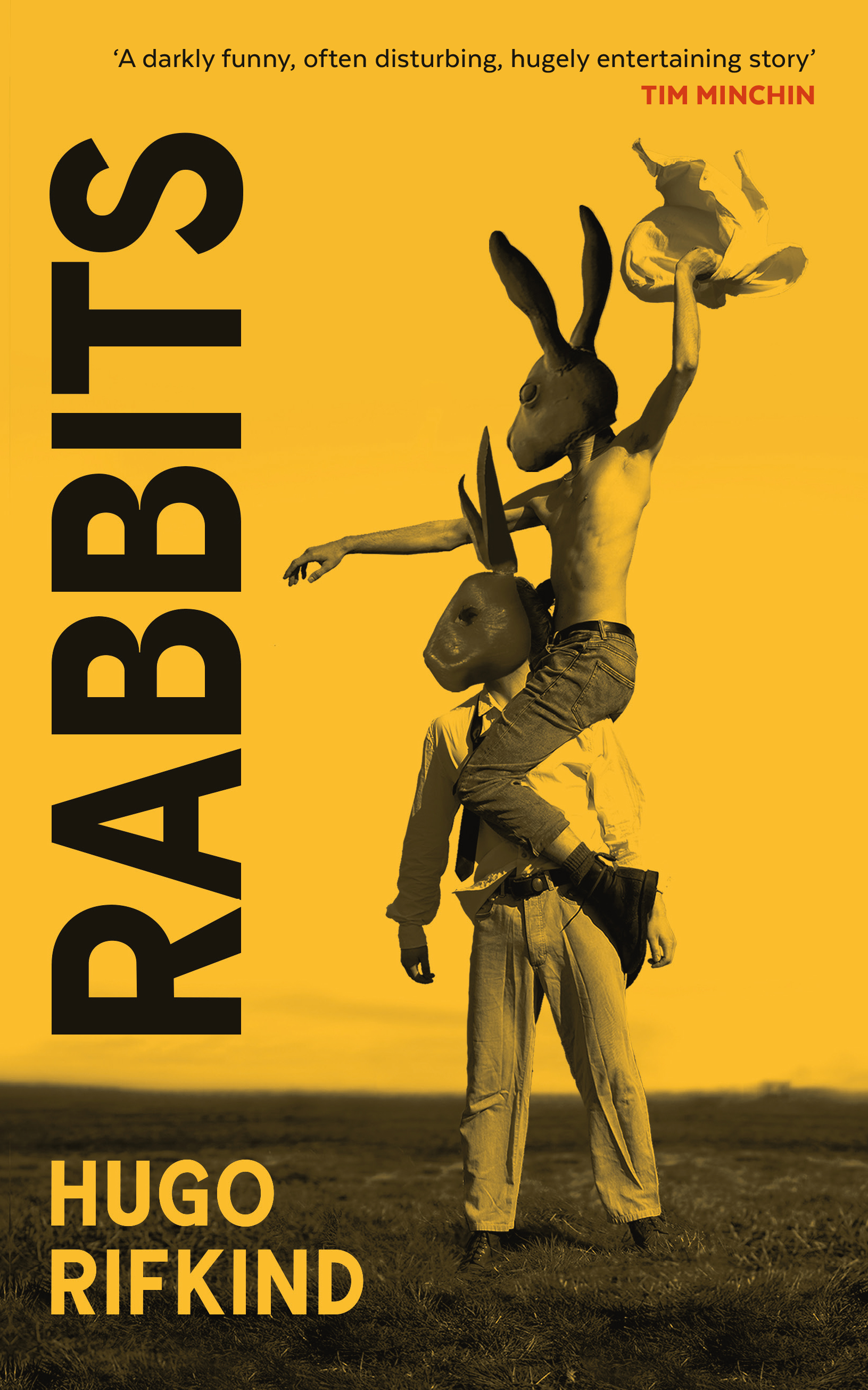

Comic novel rides the rollercoaster of 1990s teenagerdom among the Scottish elite

In some ways I’m an appropriate person to review Hugo Rifkind’s new novel Rabbits, a coming-of-age comedy set in the early Nineties. I’m about the same age as Rifkind, and was going through the agonies of school and university, drinking and girls at the same time as his protagonist Tommo.

But Rifkind is, to an extent, writing what he knows: the product of an elite Scottish boarding school, son of a famous father (in the author’s case, the Foreign Secretary, in Tommo’s, the author of a hit series of declassé novels) and mother suffering from multiple sclerosis, who ends up studying Philosophy at Cambridge. But I sincerely hope that it is all exaggerated for effect: surely no one could smoke, drink and inhale that much and live into their thirties?

But what could have become a wearying parade of accounts of debauched nights in the Highlands – and Rabbits does flirt with being just that – is saved by a couple of things. For one, Tommo is an outsider, initially baffled to be welcomed into a new social world, and always at one remove. The other is the comic tone, combining Adrian Mole, Withnail and I and Iain Banks by way of Kingsley Amis, which is engaging, and has a good hit-rate of gags, buffered by a nice line in self-deprecation.

The story starts with the tragic death of Douglas, Tommo’s friend Johnnie’s big brother, from an apparently accidental shooting. We follow Tommo from when he joins his posh school – and I don’t know how much of this section is true to Rifkind’s own experience, but it sounds pretty ghastly – to Cambridge, in which time he attends countless parties, attaching himself to numerous dodgy friends and variously appealing girls. There is an undertow of menace, with an underlying mystery of what happened to Douglas and hints of catastrophe to come.

Class is ever-present as an issue. Tommo is looked down on as his father writes novels about a crime solving butler, far from the family money of his classmates. But at the same time the landed families’ wealth seems to be teetering on the brink: the houses are grand, but the falling apart, and everyone seems to hate each other, getting progressively older, fatter and less likeable as time passes.

Class is ever-present as an issue. Tommo is looked down on as his father writes novels about a crime solving butler, far from the family money of his classmates. But at the same time the landed families’ wealth seems to be teetering on the brink: the houses are grand, but the falling apart, and everyone seems to hate each other, getting progressively older, fatter and less likeable as time passes.

Some class issues are specifically Scottish: “He had one of those Edinburgh voices where the Scottishness is almost, but not entirely, imperceptible.” (Very like Hugo Rifkind’s own, in fact.) There are also nicely observed scenes of social comedy as Tommo goes from being a servant “beater” at a shoot to an actual invited “gun”, at which point he disgraces himself by shooting a rabbit. Indeed the rabbits of the title pick out this class distinction: the upper classes shoot grouse and pheasant while rabbits are the night-time prey of the drunken, stoned Tommo and Johnnie.

There were moments when my student days came flooding back in a Proustian rush. “She had messed-up Courtney Love make-up beneath her scarlet hair, and where others wore heels, she wore Doc Marten boots.” Yes! That’s what it was like! Or “We were somehow out behind the big, high hedge that separated the driveway from the fields, and her squirming tongue was in my mouth and mine was in hers. She tasted of cigarettes and wine and, feasibly, just a touch, of vomit.” Ah, heady days! There is a lovely turn of phrase on every page: old people dancing at a Highland dance “like showponies I’d seen on telly doing dressage at the Olympics”, or Tommo hugging his mother “like she was a bunch of delicate lightbulbs in a bag,” or the neat capturing of the customary teenage preoccupation with how other people see us: “I didn’t want to suddenly be cool. I wanted to have always been cool, but in a way that people were only just noticing.”

Tommo’s parents are largely absent, opening up opportunities for adventure in the best tradition of the Famous Five. But by the end there is just a hollow sadness left, the comic tone hiding unspoken pain and emptiness beneath. Couched from the perspective of 10 years after the events took place, there is the beginning of self-knowledge in Tommo: “These days I feel like I don’t know anything… Back then, though, I knew it all.” But it’s apparent Tommo and Johnnie’s life-threateningly risky behaviour is a response to abandonment by those notionally in charge.

Rabbits is initially pegged to its time only through scattered topical references – John Major, Underworld – and the lack of mobiles. But by the end they are starting to appear, starting their revolution of the way young people interact and, in its broader themes, it becomes clear this story is set in a very particular late-Major, pre-Blair world.

Rifkind’s novel is his first since his dubious 2006 debut OverExposure, which we can perhaps most politely consider “of its time”. Like his first, Rabbits is for the most part populated by pretty unlovable people who become progressively less lovable. But it is saved by a wider social and historical resonance, a sympathetic narrator who just needs a big hug, and a readable style that keeps the pages turning.

- Rabbits by Hugo Rifkind (Birlinn, £14.99)

- More book reviews on theartsdesk

rating

Explore topics

Share this article

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Books

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

'We are bowled over!' Thank you for your messages of love and support

Much-appreciated words of commendation from readers and the cultural community

Frances Wilson: Electric Spark - The Enigma of Muriel Spark review - the matter of fact

Frances Wilson employs her full artistic power to keep pace with Spark’s fantastic and fugitive life

Frances Wilson: Electric Spark - The Enigma of Muriel Spark review - the matter of fact

Frances Wilson employs her full artistic power to keep pace with Spark’s fantastic and fugitive life

Elizabeth Alker: Everything We Do is Music review - Prokofiev goes pop

A compelling journey into a surprising musical kinship

Elizabeth Alker: Everything We Do is Music review - Prokofiev goes pop

A compelling journey into a surprising musical kinship

Natalia Ginzburg: The City and the House review - a dying art

Dick Davis renders this analogue love-letter in polyphonic English

Natalia Ginzburg: The City and the House review - a dying art

Dick Davis renders this analogue love-letter in polyphonic English

Tom Raworth: Cancer review - truthfulness

A 'lost' book reconfirms Raworth’s legacy as one of the great lyric poets

Tom Raworth: Cancer review - truthfulness

A 'lost' book reconfirms Raworth’s legacy as one of the great lyric poets

Ian Leslie: John and Paul - A Love Story in Songs review - help!

Ian Leslie loses himself in amateur psychology, and fatally misreads The Beatles

Ian Leslie: John and Paul - A Love Story in Songs review - help!

Ian Leslie loses himself in amateur psychology, and fatally misreads The Beatles

Samuel Arbesman: The Magic of Code review - the spark ages

A wide-eyed take on our digital world can’t quite dispel the dangers

Samuel Arbesman: The Magic of Code review - the spark ages

A wide-eyed take on our digital world can’t quite dispel the dangers

Zsuzsanna Gahse: Mountainish review - seeking refuge

Notes on danger and dialogue in the shadow of the Swiss Alps

Zsuzsanna Gahse: Mountainish review - seeking refuge

Notes on danger and dialogue in the shadow of the Swiss Alps

Patrick McGilligan: Woody Allen - A Travesty of a Mockery of a Sham review - New York stories

Fair-minded Woody Allen biography covers all bases

Patrick McGilligan: Woody Allen - A Travesty of a Mockery of a Sham review - New York stories

Fair-minded Woody Allen biography covers all bases

Howard Amos: Russia Starts Here review - East meets West, via the Pskov region

A journalist looks beyond borders in this searching account of the Russian mind

Howard Amos: Russia Starts Here review - East meets West, via the Pskov region

A journalist looks beyond borders in this searching account of the Russian mind

Henry Gee: The Decline and Fall of the Human Empire - Why Our Species is on the Edge of Extinction review - survival instincts

A science writer looks to the stars for a way to dodge our impending doom

Henry Gee: The Decline and Fall of the Human Empire - Why Our Species is on the Edge of Extinction review - survival instincts

A science writer looks to the stars for a way to dodge our impending doom

Jonathan Buckley: One Boat review - a shore thing

Buckley’s 13th novel is a powerful reflection on intimacy and grief

Jonathan Buckley: One Boat review - a shore thing

Buckley’s 13th novel is a powerful reflection on intimacy and grief

Add comment