Published in the year following Orr’s death at the age of 57, Motherwell is an analysis of the author’s childhood in Motherwell, on the outskirts of Glasgow, and her first steps into adulthood. However, while this book is ostensibly about Deborah Orr the child, it is as much about her parents, John and Win, and about Deborah Orr the adult. Everything seeps into everything else, just as Win seeped into Orr’s life, claiming her daughter’s whole being as her own. As Orr recognises in retrospect, “I realise now that my mother’s main trouble was her pathological inability to understand at all that I was a separate entity from her.” Motherwell struggles with this – Orr’s deep love for her parents, and her realisation that they had left her with inerasable emotional scars.

Motherwell, we cannot forget, is not only a punning description for the book's contents, but also the town itself. Orr writes about it with tenderness, but also with an awareness of the failings of the place and of all the changes it has undergone during and since her childhood, both positive and negative. This encompasses her feelings about her economic background and the massive changes seen within a generation. Her father was unable to write with any confidence, his daughter a star of print media. In this shift we can also see the move from a blue- to a white-collar workforce, and the shattering collapse of industry in a town whose identity was so closely linked to the steelworks that that it clung onto them "for dear life, like a baby monkey clings to its mother’s back”.

Central to the book is the concept of narcissism, how this trait manifests, and how it affected the Orr family dynamic. Her brother rarely figures, and when he does, he is described fairly passively. Although Orr went through periods of not talking to him, he is a relatively benign figure. It even takes Orr 103 pages to reach her own problematic ex-marriage. It is the parental relationship that Orr focuses on, ascribing narcissistic traits to both parents at various points during the book. We think that it is Win, with her selfishness, her pains, and her manipulative behaviour, who is the narcissist. But then at times it can be John, with his trenchant and unforgivingly old-fashioned views. Together, they are united in their co-dependency, which is both endearing and toxic, as well as occasionally deeply troubling.

Central to the book is the concept of narcissism, how this trait manifests, and how it affected the Orr family dynamic. Her brother rarely figures, and when he does, he is described fairly passively. Although Orr went through periods of not talking to him, he is a relatively benign figure. It even takes Orr 103 pages to reach her own problematic ex-marriage. It is the parental relationship that Orr focuses on, ascribing narcissistic traits to both parents at various points during the book. We think that it is Win, with her selfishness, her pains, and her manipulative behaviour, who is the narcissist. But then at times it can be John, with his trenchant and unforgivingly old-fashioned views. Together, they are united in their co-dependency, which is both endearing and toxic, as well as occasionally deeply troubling.

In a sense, therefore, Motherwell acts as catharsis following her mother’s death. And in the proximity of her own, Orr recognises “I can only say it all because she is dead. Is memoir therapy? Or is it vengeance?”. Orr is quite literally setting her familial house in order, starting with the bureau and ending with the cupboard. The bureau which was once the centre of Orr family administration is both furniture and the device from which items can be taken that begin new strands of narrative. Although Orr occasionally digresses, she always brings the story back to her family – this is a tightly controlled book in many ways, and nothing feels extraneous. That the bureau is so central to her mother’s own control turns this simple object into a symbol, a signifier of power that is cancelled in a stroke when Orr sells it for £40 after her mother’s death. The cupboard only appears towards the end of the book and, while Orr will not let her text end neatly here, is her exoneration, the evidence that her parents were proud of their daughter, despite all their behaviour – it had clippings of every article Orr ever wrote.

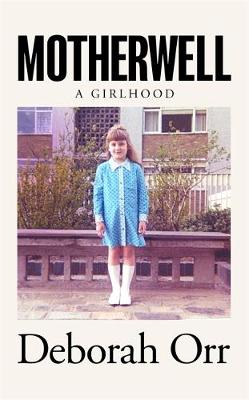

- Motherwell by Deborah Orr (Weidenfeld & Nicolson, £13.99)

- Read more book reviews on theartsdesk

Add comment