Maria Reva’s humorously gloomy debut collection, centring on the inhabitants of a block of stuffy apartments in Soviet (and post-Soviet) Ukraine, starts, predictably enough, with Lenin. Instead of an austere symbol of ideology, he’s a statue who “squinted into the smoggy distance. Winter’s first snowflakes settled on its shoulders like dandruff.” A clumsy figure, whimsically at one with the amplified dreariness around him, he fits comfortably within the brisk, deadpan comedy of the stories that follow. By the end of the book, he’s been reduced to “a concrete pedestal”. “Only his feet remain now, big as bathtubs, rusty rebar curving from them like veins.”

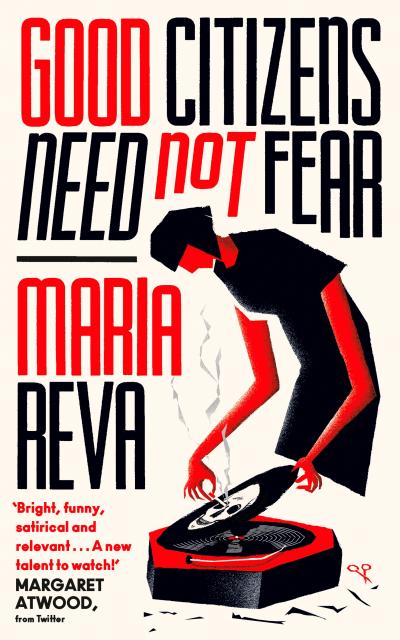

Carefully balancing the absurd with the grimly ordinary, and the measured with the knowingly overblown, Good Citizens Need Not Fear looks at life in the years just before (and following) the end of the Soviet era with a surrealist, often satiric squint. Most of the characters are residents at Number 1933 Ivansk, an apartment block deemed not to exist by state bureaucracy. Alongside a Madagascar hissing cockroach, studded with gems and attached to a chain, 1933 Ivansk’s inhabitants include agoraphobic widow Smena, making a pretty penny from “bone music” (bootlegged records transferred onto radiographic film), poet Konstantyn Illych, who starts a business charging pilgrims to peer at a saint’s shrunken form, and the 14 family members squashed inside chilly Suite 56 (Grandfather Grishko among them: so cold “he hasn’t seen his own testicles in weeks”).

Reva’s clever interweaving of these stories mimics the squashing together of the block’s inhabitants – a joke at the state’s attempt to circumscribe the “Minimum Dimensions of Space Necessary for Human Functioning”. Yet the structure of careful reappearances also points to the more general imperative to be resourceful: to reinvent yourself (though not too obtrusively) according to changing circumstances. Konstantyn Illych, pursued in one story by a secret service agent intent on making him apologise for a political joke, emerges later as the Director of the increasingly deserted Kirovka Cultural Club pioneering the USSR's first beauty pageant. The agent himself returns too: a reluctant guard to the toothy saint’s popular tomb. Milena Markivna, Konstantyn’s wife, surfaces variously as a rapier-wielding torture artist, Smena’s bone music dealer, and, more gently, one half of two seamstress lovers, sewing fur coats on the black market to feed a family of four.

Throughout these stories, Reva’s characters are defiant, witty and long-suffering. They make do with the restrictions on their freedom, alongside shortages and impossible demands. Daniil, an employee at the Kirovka Canning Combine, discovers a memo on his desk: “To fill unfillable string-bean triangular void, engineer triangular vegetable. Due Friday.” (Milena, later, will ask about “the exploding cans”, presumably the result). It’s not all farce, however. The skill of Reva’s writing is in the empathy of its comedy: although the predominant tone is of mischievous entertainment, there are heartfelt moments of tenderness, loss and hurt. A father mourning his wife’s absence: “every evening, when he thought I was asleep on the sofa beside him, [he] wrapped his fingers around the spines of the plants and winced and grit his teeth.” Or the wry reflections of those down-at-heel in post-Soviet society: “Again I missed the years when one had fewer choices, fewer ways to disappoint.”

While the narratives are attentive to the grotesque realities of Soviet Ukraine in its final years, playful visuals scattered throughout the stories interrupt with a parallel universe of literalism. There are redacted jokes, an illustration of how to make a swan from a car tyre, and a sketch of Konstantyn’s suite, perched precariously at the top of a crevasse of collapsed apartments in Ivansk 1933, making the point inescapable: it’s only a matter of time before his floor falls through. Two unpunctuated pages listing the contents of canned goods are as squashed as the canned contents themselves, culminating in a litany of “potatoes potatoes potatoes potatoes”. Even when the subject is the aerial view of unwanted babies’ beds, the ironic effect exploits the distance between the mess of lived human experience and the neatness such diagrams allege: a burlesque of control, as lively little Zaya crawls beyond the neat quadrant of the baby house, “cruising along the wooden picket fence, eyes set on a gap wide enough to squeeze through”.

In the best of these stories, the political satire happens quietly amongst all this. While the tantalisingly absurd scenarios provide a centre for intrigue, it’s in the background that neighbours report on neighbours, the central heating fails, and tourists flock to buy relics from Chernobyl. Reva sidesteps the risk of cliché via such domestic interiors, and it’s here that she engineers a winning combination of drollery and dark humour. The collection that results is consistently funny, heartening and charmingly observed.

- Good Citizens Need Not Fear by Maria Reva (Virago, £14.99)

- Read more book reviews on theartsdesk

Add comment