At the end of an exhausting week in which Holocaust Memorial Day struck a more urgent note than ever as fascism started tearing through the USA, parts of this concert were bound to hit hard. That they did so to the power of 100 was thanks to the extraordinary impact of Jakub Hrůša, now recognised as one of the greats by British audiences as he waits to take up the full-time reins at the Royal Opera. The BBC Symphony Orchestra burned for him in fullest focus.

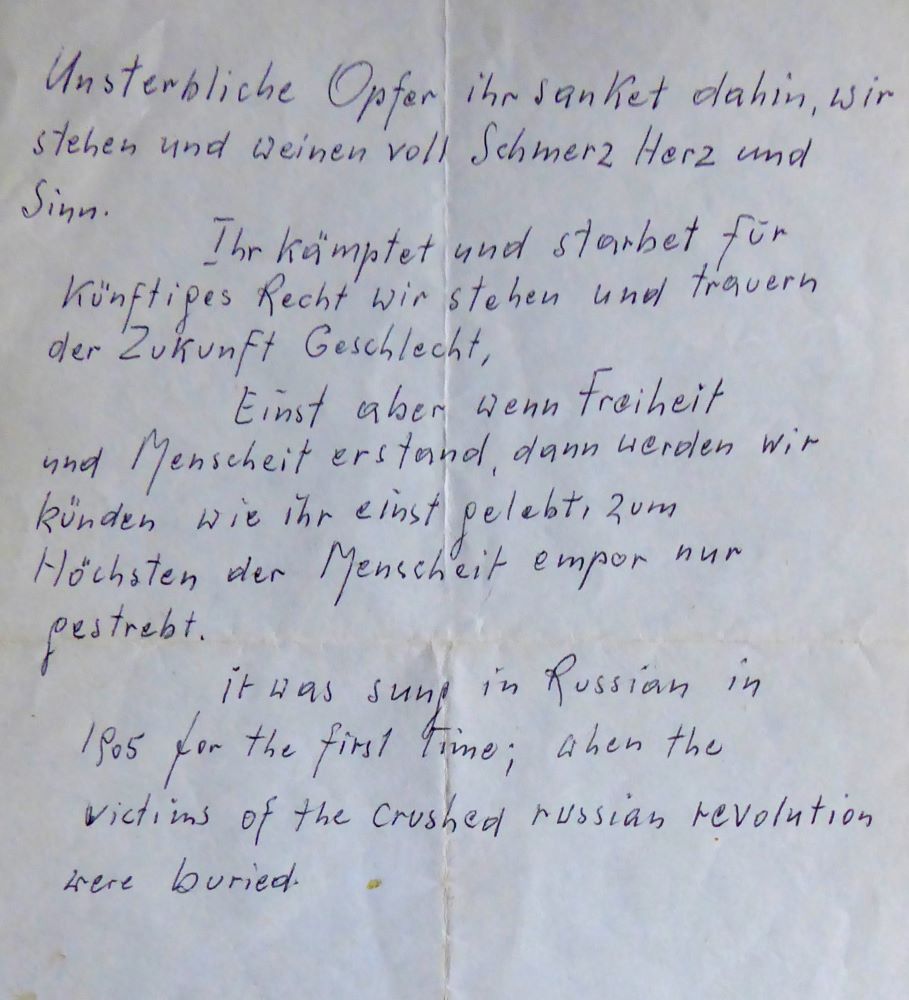

Shostakovich’s Eleventh is one of his symphonies which require special pleading (which is much better than bad, the only adjective to apply to its successor). Its use of Soviet-approved revolutionary songs, many dating back to the uprising of 1905 in which the crowds in St Petersburg’s Palace Square were massacred by the tsar’s soldiers, complicates matters; I used to think they got in the way of true expression. But it takes a great performance to show us how consummately the composer weaves them into his fabric, adding his trademark minor thirds and seconds, sometimes presenting them unvarnished before elaborating, and to highlight his unerring sense of the right orchestration for the right moment.  Hrůša, who knows from his parents’ generation about the song-filled Prague Spring of 1968 and what happened when the Soviet tanks rolled into the city, understands the emotion behind the tunes, and got the BBC Symphony players either to phrase like singers or punch the resistance home. With peerless solos from Philip Cobb’s searing muted trumpet fanfare onwards, the “Palace Square” Adagio pitted a human quickening against one enemy, freezing cold; “The Ninth of January” unleashed the other, military violence, and at such a lick (yes, the metronome marking for the massacre is fast). Other conductors have made all the bludgeoning and conflict throughout the symphony merely banal; Hrusa’s unique rubato lifted and bent them into spring-heeled shape.

Hrůša, who knows from his parents’ generation about the song-filled Prague Spring of 1968 and what happened when the Soviet tanks rolled into the city, understands the emotion behind the tunes, and got the BBC Symphony players either to phrase like singers or punch the resistance home. With peerless solos from Philip Cobb’s searing muted trumpet fanfare onwards, the “Palace Square” Adagio pitted a human quickening against one enemy, freezing cold; “The Ninth of January” unleashed the other, military violence, and at such a lick (yes, the metronome marking for the massacre is fast). Other conductors have made all the bludgeoning and conflict throughout the symphony merely banal; Hrusa’s unique rubato lifted and bent them into spring-heeled shape.

As for the many near-silences, I wonder if he could sense the intensity of the audience behind him. The air in the hall was electric as pizzicato cellos and basses ushered in the main theme of “In memoriam” on initially wan violas, warming to vibratoed life as other string sections gave them strength.

The central outpouring of this movement and its passionate counterpart in the finale can sound like Tchaikovskyan overkill; Hrůša kept them tense so that their rapid overwhelming by hostile forces seemed inevitable. Ultimately, there was the tocsin, a warning of how all this can and will happen again and again. I hope Hrůša will turn to Shostakovich’s inspiration, Musorgsky's worlds in Boris Godunov and Khovanshchina, in his time at the Royal Opera. He knows how to hold a crowd, too: the bell was allowed to resonate into silence before the entire audience rose almost instantaneously to its feet.

Hrůša has only conducted the BBCSO in one previous concert – a Proms spectacular celebrating Reformation anniversary year with variations on another popular song of great significance to a nation, the Hussite Chorale "Ye who are God's Warriors". We got to hear rarities like Suk’s gorgeous Prague for the first time. There was one Czech surprise here, at the beginning of the concert. Pavel Haas, who knowingly or not saved his friend the conductor Karel Ancerl in front of the Auschwitz gas chambers and coughed so that Mengele would choose him for murder instead, started his composing life as a pupil of Janáček at the Brno Conservatoire. Scherzo triste, his first major orchestral work of 1921, is a chip off the old block, and not just because Haas uses the ominous tritone and the whole tone scale much as Janáček does; a consolatory melody with two harps is indebted to Taras Bulba. And it’s no problem because Janáček’s orchestral works are few and far between. Haas's personal trajectory, apparently taking the master’s advice to look at Debussy’s La Mer and compose freely, takes us from the giddying macabre to a peace of sorts, his response to a failed love affair. Under Hrůša, it sounded opulent and eerily beautiful, worthy of a regular place in the repertoire.  Fullness of tone was also the orchestral keynote in Beethoven’s Second Piano Concerto, allied to perfect eloquence of phrasing. It was slightly at odds with Jonathan Biss’s more reserved approach, harvesting a good range of colours and using the sustaining pedal to magical effect at the end of the slow movement (Biss pictured above). His encore, Schubert’s D flat major Impromptu from the D899 set on the day of the composer’s birth, confirmed the feeling: perfect articulation, but a touch of emotional distance. A consummate musician on his own terms, all the same.

Fullness of tone was also the orchestral keynote in Beethoven’s Second Piano Concerto, allied to perfect eloquence of phrasing. It was slightly at odds with Jonathan Biss’s more reserved approach, harvesting a good range of colours and using the sustaining pedal to magical effect at the end of the slow movement (Biss pictured above). His encore, Schubert’s D flat major Impromptu from the D899 set on the day of the composer’s birth, confirmed the feeling: perfect articulation, but a touch of emotional distance. A consummate musician on his own terms, all the same.

- Recorded for broadcast on BBC Radio 3 on 4 February at 7.30pm

- More classical music reviews on theartsdesk

Add comment