Anthony Collins: Complete Decca Recordings (Decca Eloquence)

Anthony Collins: Complete Decca Recordings (Decca Eloquence)

Born in 1893, Anthony Collins began his musical career as a 17-year-old violist in the Hastings Municipal Orchestra. Active service in World War 1 was followed by a spell at the Royal College of Music, after which Collins established himself as a resourceful and versatile London-based musician. Peter Quantrill’s entertaining booklet essay for this 11 disc Decca Eloquence set has one wondering how such a prominent figure, renowned as a conductor, arranger, composer and performer, managed to slip into obscurity. These mono "FFR" recordings were made between 1945 and 1956, by which time Collins was better known in the UK for as a film composer than as a conductor.

Collins’ London Symphony Orchestra Sibelius cycle, one of the first complete sets to be issued, has cult status. Highlights include an exciting Symphony No. 1 and a swift, coherent take on No. 7’s single movement. Producer Victor Olof’s vivid sound can highlight the rough edges of an LSO some years away from its 1960s purple patch, but these are largely fresh and exciting performances, coupled with convincing readings of Night Ride and Sunrise and Pohloja’s Daughter. Still, Herbert von Karajan’s Philharmonia recordings of Symphonies 4-7, taped around the same time by EMI, are a more refined (and much better-played) alternative.

Collins’ London Symphony Orchestra Sibelius cycle, one of the first complete sets to be issued, has cult status. Highlights include an exciting Symphony No. 1 and a swift, coherent take on No. 7’s single movement. Producer Victor Olof’s vivid sound can highlight the rough edges of an LSO some years away from its 1960s purple patch, but these are largely fresh and exciting performances, coupled with convincing readings of Night Ride and Sunrise and Pohloja’s Daughter. Still, Herbert von Karajan’s Philharmonia recordings of Symphonies 4-7, taped around the same time by EMI, are a more refined (and much better-played) alternative.

There’s lots more. Collins was a sympathetic Mozart conductor, and the earliest item in the box is an idiomatic account of Symphony No. 33, transferred from 78s made with Collins’ own London Mozart Orchestra. Gervase de Peyer plays the Clarinet Concerto, and a young Friedrich Gulda plays three of the piano concertos with Strauss’s Burleske as an enjoyable bonus. Moura Lympany’s Rachmaninov 3rd Concerto is an enjoyable period piece, but better still are fizzing accounts of Mendelssohn’s two piano concertos with Peter Katin. Ruggiero Ricci plays Paganini, Collins offering nimble, alert support. Relatively well-known is a 1954 LP of Walton’s complete Façade with Peter Pears and Edith Sitwell as speakers. Not for everyday listening, perhaps, but the most sheerly musical performance ever recorded. Sitwell’s plummy delivery is priceless and Pears is excellent, rhythmically sharp and suitably dry.

There’s lots more. Collins was a sympathetic Mozart conductor, and the earliest item in the box is an idiomatic account of Symphony No. 33, transferred from 78s made with Collins’ own London Mozart Orchestra. Gervase de Peyer plays the Clarinet Concerto, and a young Friedrich Gulda plays three of the piano concertos with Strauss’s Burleske as an enjoyable bonus. Moura Lympany’s Rachmaninov 3rd Concerto is an enjoyable period piece, but better still are fizzing accounts of Mendelssohn’s two piano concertos with Peter Katin. Ruggiero Ricci plays Paganini, Collins offering nimble, alert support. Relatively well-known is a 1954 LP of Walton’s complete Façade with Peter Pears and Edith Sitwell as speakers. Not for everyday listening, perhaps, but the most sheerly musical performance ever recorded. Sitwell’s plummy delivery is priceless and Pears is excellent, rhythmically sharp and suitably dry.

The orchestral selections are consistently enjoyable. Collins’ 1952 Elgar Falstaff is affectionate and full of detail, and his Vaughan Williams Tallis Fantasia glows. Delius’s Paris meanders a bit, but some shorter Delius pieces sound well and don’t drag. A 1957 recording of Percy Grainger’s Shepherd’s Hey is incredibly vivid, with incisive percussion and superb trombones. Collins’ own Vanity Fair and With Emma to Town are charming miniatures. The Grainger was one of the very last things Collins recorded; by then he had taken short-term charge of the Cape Town Municipal Orchestra before returning to Los Angeles, dying there in 1963. Eloquence’s packaging is typically pleasing, with Decca’s original sleeve art reproduced on the individual discs. A fulsome tribute to a musician who really does deserve to be better known.

Schumann: Alle Lieder Christian Gerhaher, Gerold Huber (Sony)

Schumann: Alle Lieder Christian Gerhaher, Gerold Huber (Sony)

German baritone Christian Gerhaher and pianist Gerold Huber reveal some absolute gems in their remarkable new 11-CD compilation of songs by Schumann. The pair, both from the same town in Bavaria and born in the same year, set out with a shared goal: they believe in Schumann and put their trust in his genius. If there are a host of glorious and relatively unknown songs to be found here, it is because Gerhaher, Huber and the other singers on their team have put in the dedicated work to understand them so deeply.

One among hundreds of examples of their subtle and patient mastery is “Ich hab’ in mich gesogen” from the Liebesfrühling Op. 37 on CD2. Huber’s weighting of the persistent accent on the sixth quaver of the 4/4 bar, the pair’s respect for the marking “einfach innig” (simply intimate) makes one reflect on why a song as wonderful as this doesn’t get performed more often. Or take a song on CD10 sung by one of the other singers from "team Gerhaher", “Mond, meiner Seele Liebling” (Moon, my soul's darling) from the Kulmann songs Op. 104, sung by Sibylla Rubens. She also performed this song on the Naxos cycle, but Huber’s pacing of it is in a wholly different class.

Another joy is the hushed concentration Gerhaher and Huber can bring to a song like “Zum Schluss” from Myrthen. This reading would be too quiet for a concert hall, but here every quiet nuance has been perfectly caught; it forces one to listen intently. At the opposite end of the scale, the occasions when Gerhaher does (to quote Die Löwenbraut) “brüllet mit macht” (roars powerfully), they are mercifully few and far between. We hear it in an impassioned “Entflieh’ mit mir und sei mein Weib” (Elope with me and be my wife) from Op. 64, a song which would lose its whole purpose and effect if wimped. For my own amusement, I went back to that delightfully reassuring moment in the Fischer-Dieskau set where the great man ceases to be a God and fluffs Heine’s words in “Mein Wagen rollet langsam” from Op. 142. The difference is clear: Gerhaher and Huber give themselves all the time in the world to tell the story clearly and impeccably – and yet also with a conspiratorial smile and a tease.

This set has been a huge enterprise. One of the recordings from the studios of Bavarian Radio was made back in 2004 (by an engineer who is delightfully and genuinely named Wilhelm Meister), with most from the period 2017-2020. The 216-page booklet is meticulously put together, but there are no translations of song texts. There is, however, thoughtful and lively writing to be enjoyed in German and good English, with everything from a description of “Die beiden Grenadiere” as "a comic strip”, to reflections on the feigned death in Schubert’s Winterreise versus the "real" one in the Kerner-Lieder. And Gerhaher takes the trouble to explain in depth in his booklet essay how this collection differs from its predecessors, notably the Fischer-Dieskau LPs with Christoph Eschenbach from the late 1970’s and the Graham Johnson set taped from 1997 onwards. This Sony release does indeed break new ground. The total miracle of 1840, the "year of song", has probably never been portrayed with such immediacy as here. And Gerhaher and Huber have thought deeply and over many years about Schumann’s way of arranging songs in cycles. Alle Lieder is an indispensable box. – Sebastian Scotney

Komitas and Bartók: Folk Tunes Steffen Schleiermacher (piano) (MDG)

Komitas and Bartók: Folk Tunes Steffen Schleiermacher (piano) (MDG)

“I will collect the most beautiful Hungarian folk songs and raise them to the level of art songs with the best possible piano accompaniment.” So wrote Bartók in a letter to his sister in 1904, before setting out to transcribe what he discovered in Slovakia and Eastern Hungary. Many were recorded on wax cylinders and some examples can be found on YouTube. They’re extraordinary documents, their raw power transcending the dim, scratchy sound. Pianist Steffen Schleiermacher’s excellent notes quotes from some of Bartók’s later letters, the composer complaining that it was difficult, as an urbane "stranger from the city" to persuade older women to sing for him (“it is better to be alone with them”). That some rural villagers would only sing lullabies in the evenings and wedding songs at actual marriages was a source of frustration, Bartók often returning from expeditions with barely anything to show for them. This disc is a find, with four of Bartók’s sets of folk tunes intriguingly coupled. The Fifteen Hungarian Peasant Songs have a lovely ebb and flow here, Schleiermacher sounding as if he’s improvising on the fly, and he throws in peerless accounts of the two sets of Romanian Christmas Carols. MDG’s engineering is gorgeous.

Soghomon Gevorki Soghomonian, better known as Komitas, was an Armenian composer and musicologist, born several decades before Bartók. The two composers never met, though Schleiermacher suggests that they must have been aware of each other’s work. Ordained as a priest in 1890, Komitas too set out to transcribe folk songs, in his case exploring Kurdish, Turkish and Persian music as well as that of Armenia. Moving to Constantinople in 1910, Komitas was later arrested and deported by the Turkish authorities, spending the years until his death in 1935 in French sanatoriums, abandoning his folk song collecting. He’s still revered in Armenia; hopefully this disc will bring him wider recognition. Komitas’s transcriptions are simpler, less interventionist than Bartók’s. Several melodies reappear in different settings; “I’m a Girl” and “Water flowing from the High Mountain” from the 1910 12 Pieces for Children turn up in 1911’s Seven Songs. Many of the pieces are tiny, and it’s striking how Komitas can suggest so much in just a few bars. “The Sun, the Sun” is a slice of bright radiance lasting just 27 seconds. Try the Seven Dances, premiered in Paris in 1906 and admired by Debussy and Saint-Saens. How can this repertoire be so little-known? Schleiermacher is a persuasive guide; if you’re fond or Satie, or Mompou, you need to make space for Komitas.

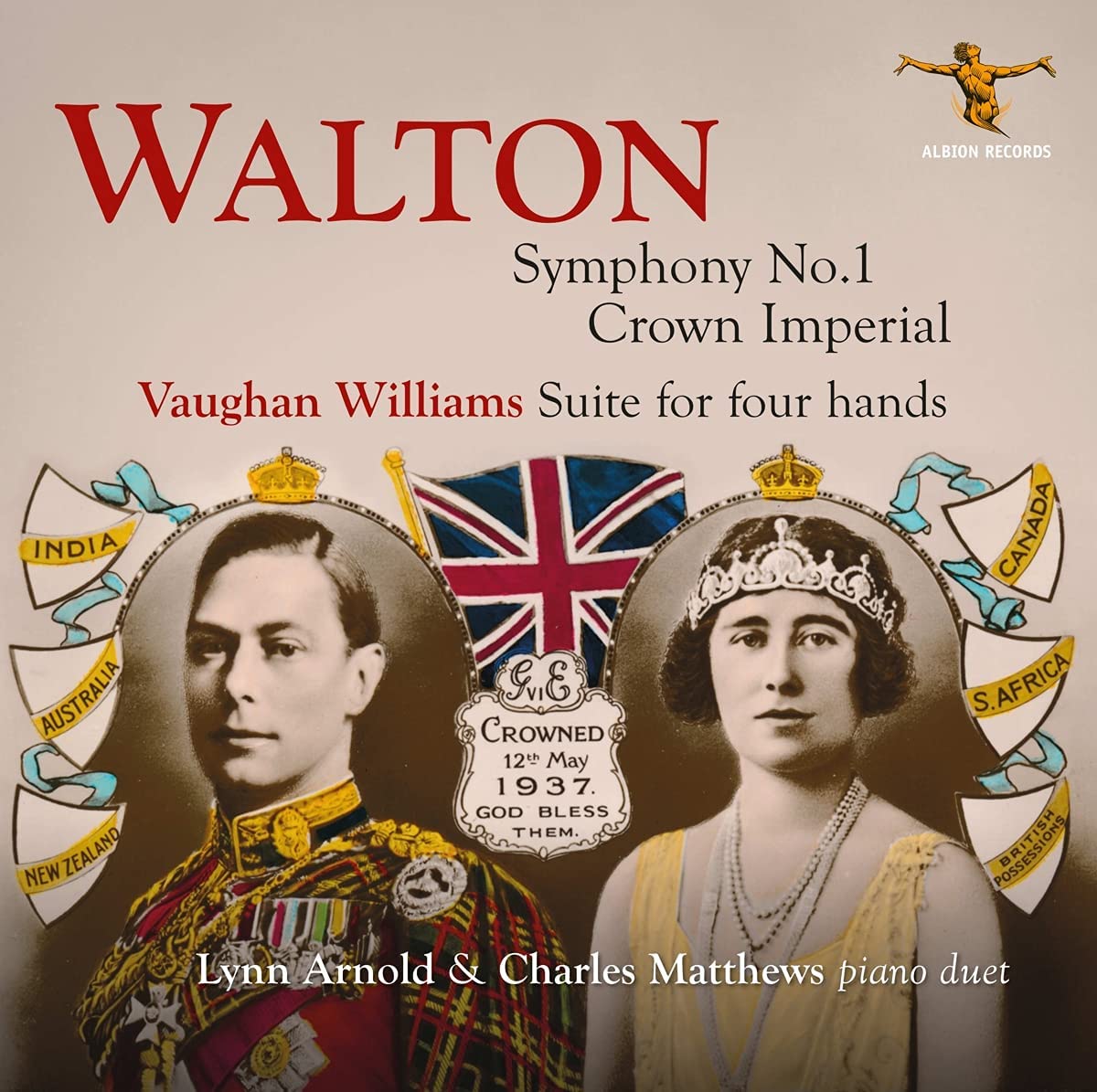

Walton: Symphony No. 1, Crown Imperial, Vaughan Williams: Suite for four hands Lynn Arnold & Charles Matthews (piano duet) (Albion Records)

Walton: Symphony No. 1, Crown Imperial, Vaughan Williams: Suite for four hands Lynn Arnold & Charles Matthews (piano duet) (Albion Records)

Musically, Vaughan Williams and Walton might not seem to have much in common – though the senior composer liked Belshazzar’s Feast and the Viola Concerto, and Walton was a fan of Vaughan Williams’s quirky 8th Symphony. Ralph and Ursula Vaughan Williams enjoyed a holiday in Ischia as guests of the Waltons in 1958, and both men worshipped Sibelius. This main draw on this entertaining CD is a piano duet version of Walton’s Symphony No. 1, made two years after the work’s premiere by Herbert Murrill, then Professor of Composition at the Royal Academy of Music. A contemporary review described the transcription as having “some formidable and strenuous pages… more likely to be tackled by serious students than duettists giving an evening’s entertainment.” Lynn Arnold and Charles Matthews are much more than serious students; this performance is mostly a blast, and recommended to anyone who loves this symphony. There’s a lot of gnarly basso writing in Walton’s first movement, and while the opening timpani roll lacks mystery as a low piano roll, hearing the chords as actual notes rather than murky clouds of sound is a revelation. Plus, the playing is so sharp and punchy, this performance lasting just under 45 minutes. The first movement’s quiet centre is eerily spare and desolate, the coda exultant. Murrill’s version of the scherzo could pass for a Prokofiev sonata in places, and the “Andante con malinconia” is all the more poignant heard in monochrome. Murrill’s duet version of Crown Imperial is fun – again, it’s satisfying to hear the chords so clearly, Arnold and Matthews favouring energy and exhilaration over bombast.

Between these two works comes Vaughan Williams’s Suite for Four Hands on One Pianoforte, written in 1893 while its composer was a history student at Cambridge, the unpublished manuscript now in the British Library. A thorny piece of baroque pastiche, it’s totally uncharacteristic but very striking, the craggy “Prelude” a real attention-grabber. All three works are premiere recordings, and you can’t imagine them being better served.

20th Century Foxtrots Vol. 2 – Germany Gottfried Wallisch (piano) (Grand Piano)

20th Century Foxtrots Vol. 2 – Germany Gottfried Wallisch (piano) (Grand Piano)

This is intoxicating fun: a disc of foxtrots from post-World War I Germany. How jazz reached the country is up for debate; the Treaty of Versailles banned the import of foreign cultural goods (ie 78rpm records), and radio stations didn’t start broadcasting until 1923. Many prominent cultural figures weren’t fans: Stefan Zweig described jazz’s rapid spread as a “monotonisation of the world”, and politicians on the right spoke of jazz having "infected" the nation. Gottlieb Wallisch gives us 29 numbers on this CD, the earliest one from Paul Hindemith, who’d encountered jazz while playing in Swiss spa orchestras. The 1922 “Dance of the Wooden Dolls” from his enchanting ballet Tuttifäntchen is a charmer. Other well-known names include pianist Walter Gieseking, whose set of Three Dance Improvisations includes a terrifically catchy Charleston, and Kurt Weill – Wallisch plays the “Tango-Ballade” from The Threepenny Opera and a pair of bittersweet numbers composed in 1934 for Jacques Deval’s play Marie Galante. This anthology lasts for 66 minutes, but you’ll need several hours to absorb it fully: each new, unknown dance number sent me down a Wikipedia and YouTube rabbit hole in search of more information about the likes of Max Butting, Bernhard Seckles and Siegfried Borris.

Selected highlights would have to include Fidelio F Finke’s little “Shimmy”, taken from a set of children’s pieces, and an idiomatic “Blues” by Eugen d’Albert. Plus Leopold Mittmann’s Concert Jazz Suite, each of its three numbers channelling Gershwin. The last one, enticingly titled “Hot”, is superb. It’s all brilliant. Stick this disc on shuffle if you ever get to host a dinner party – your guests will thank you. Wallisch’s playing combines virtuosity with the lightest of touches, and the close, immediate recording balance suits this repertoire well.

Add comment