Elysian Singers, SPCMH, Sam Laughton, St Luke’s, Chelsea review - John Cage and friends given a rare airing | reviews, news & interviews

Elysian Singers, SPCMH, Sam Laughton, St Luke’s, Chelsea review - John Cage and friends given a rare airing

Elysian Singers, SPCMH, Sam Laughton, St Luke’s, Chelsea review - John Cage and friends given a rare airing

Adventurous choral modernism alongside entertainingly anarchic postmodernism

In my reviewing for theartsdesk I like as much as possible to ski off-piste, reaching areas of repertoire, performer and venue that mainstream coverage doesn't. There is much great music-making that flies, to mix my metaphors, under the radar, but which is well worthy of being written about.

The title of the concert – “John Cage and Friends” – was, as the Elysian’s conductor Sam Laughton (pictured below) conceded, a bit misleading. The composers featured were so various that finding a unifying thread would be impossible, but Cage’s status as, in his own term, the great “permission-giver” made his as good a banner as any for this ship to sail under. The concert fell into two halves, with first the Elysians singing some knotty and at times challenging music that was nevertheless conventional choral music, followed by the SPCMH recreating a '70s postmodernist vibe in its “anything goes” free-form set. The finale was both groups coming together for Eric Whitacre’s Cloudburst, which calls for a panoply of percussion, from handbells to bass drum.

The Elysian Singers opened with Per Nørgård, whose Wie ein Kind derives from his long-standing obsession with the writings of Adolf Wölfli, a Swiss writer and artist who suffered from schizophrenia, and whose often fantastical and nonsensical writing have been the basis of several pieces by Nørgård. A sample of the text for this piece gives a flavour: “G’ganggali ging g’gang, g’gung g’gung!” It is given a chordal setting, interrupted by outbursts of shouts and cries – Helly Summerly giving a particularly striking solo here amid a steadfast performance. The central movement is a very challenging sing, the Elysians dealing with the chromatic lines unhesitatingly.

The Elysian Singers opened with Per Nørgård, whose Wie ein Kind derives from his long-standing obsession with the writings of Adolf Wölfli, a Swiss writer and artist who suffered from schizophrenia, and whose often fantastical and nonsensical writing have been the basis of several pieces by Nørgård. A sample of the text for this piece gives a flavour: “G’ganggali ging g’gang, g’gung g’gung!” It is given a chordal setting, interrupted by outbursts of shouts and cries – Helly Summerly giving a particularly striking solo here amid a steadfast performance. The central movement is a very challenging sing, the Elysians dealing with the chromatic lines unhesitatingly.

The Elysians have a long association with James MacMillan, who is their patron. His Changed was accompanied by three muted trombones playing a solemn ostinato, the choir overcoming a slightly uncertain start to reach a full-voiced climax, while The Rising Moon was augmented by handbells and vibraphone, deftly played by Matt Venvell.

The two pieces by Jonathan Harvey were both written for Winchester Cathedral. I love the Lord has a lovely smudged sonority, as half the choir sustains a pedal chord while the rest move to an adjacent harmony. The Eliot setting The dove descending was strident and dissonant, the choir focused and stern, organ scrunches supplying a fiery redemption.

The John Cage choral piece, Four2, showed perhaps why he is more talked about than performed: the piece was fine, but more interesting in conception than in aural experience. Aleatoric, allowing the conductor freedom in bringing parts in and out, the harmony that resulted from long sustained notes was banal, and lacking the magical simplicity that someone like Howard Skempton can conjure.

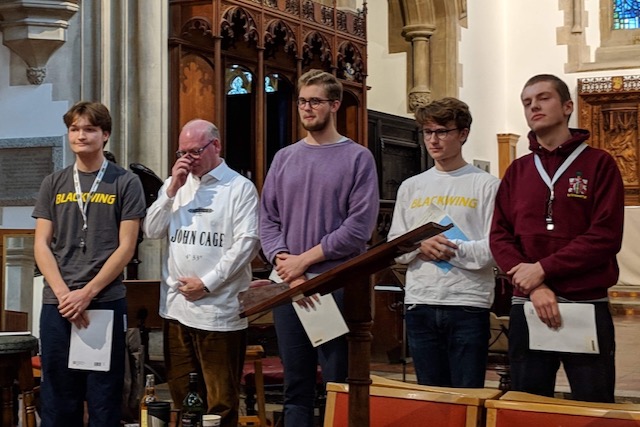

Jeremy Summerly (pictured left) is well-known as the conductor of the Oxford Camerata, whose recordings for Naxos of early choral repertoire are much-loved staples. In his time as Director of Music at St Peter’s College, Oxford, he initiated the St Peter’s Contemporary Music Happening, the group comprising the four final year undergraduates performing alongside Summerly himself. As Summerly admitted in his introductory comments, a lot of the music featured is no longer contemporary, dating from the 1950s and '60s, suggesting perhaps that today’s experimental musicians are working in different media, such as computer music or film.

Jeremy Summerly (pictured left) is well-known as the conductor of the Oxford Camerata, whose recordings for Naxos of early choral repertoire are much-loved staples. In his time as Director of Music at St Peter’s College, Oxford, he initiated the St Peter’s Contemporary Music Happening, the group comprising the four final year undergraduates performing alongside Summerly himself. As Summerly admitted in his introductory comments, a lot of the music featured is no longer contemporary, dating from the 1950s and '60s, suggesting perhaps that today’s experimental musicians are working in different media, such as computer music or film.

But there was no doubt this half-hour set – put together with a care that belied its chaotic surface – was entertaining and enjoyable, even if it felt more museum-piece than cutting-edge. (Perhaps this school of music went so far down the road that it reached a dead-end?) We started with John Cage’s antic Solo for sliding trombone, played here, with appropriate perversity by two trombonists, Joe Smales and Felix Fardell, who explored a range of ways of making sounds from the trombone, from playing with mutes, actually playing the mutes themselves, deconstructing the instruments and even, on the odd occasion, blowing a normal note through the instrument.

One of the two rules of the SPCMH (pictured below) is that they always include the jazz standard “Autumn Leaves” in some form. Here it came mashed-up with an In Nomine by Robert White (1538-74) arranged for a “broken consort” of two trombones, recorder, harpsichord and vibes, slipping into barbershop harmonisation and finally plainchant (both very impressively sung). Finn Blakey gave an exceptional, virtuosic reading of Georges Asperghis’s Récitations op 46 no 8 from the pulpit, while Summerly and Matt Venwell clapped their way through Pascal Zavaro’s Kino-Klapp, with its nod to Steve Reich’s Clapping Music.

They finished with a combination of two of LaMonte Young’s famous “instruction” pieces from 1960. One gives two pitches which have to be sustained “for a long time” and the other consists entirely of the words “most of them were very old grasshoppers”. The latter part was interpreted by Felix Fardell bouncing out through the audience, while the other players reiterated the B and F-sharp (although I’d question whether it qualified as “for a very long time”).

They finished with a combination of two of LaMonte Young’s famous “instruction” pieces from 1960. One gives two pitches which have to be sustained “for a long time” and the other consists entirely of the words “most of them were very old grasshoppers”. The latter part was interpreted by Felix Fardell bouncing out through the audience, while the other players reiterated the B and F-sharp (although I’d question whether it qualified as “for a very long time”).

The set was performed with the necessary deadpan seriousness, allowing the moments of humour to emerge better, and the musical juxtapositions were a revealing collage. Ending with the Whitacre was – for all its strengths – something of an anti-climax, bringing us back into the world of conventional performance. Cloudburst sounded good, as it usually does, but for me needs a bigger choir, both for the vocal climax and the clicking and thigh-slapping that recreates the rainfall: in this case more is more.

rating

Explore topics

Share this article

Add comment

The future of Arts Journalism

You can stop theartsdesk.com closing!

We urgently need financing to survive. Our fundraising drive has thus far raised £49,000 but we need to reach £100,000 or we will be forced to close. Please contribute here: https://gofund.me/c3f6033d

And if you can forward this information to anyone who might assist, we’d be grateful.

Subscribe to theartsdesk.com

Thank you for continuing to read our work on theartsdesk.com. For unlimited access to every article in its entirety, including our archive of more than 15,000 pieces, we're asking for £5 per month or £40 per year. We feel it's a very good deal, and hope you do too.

To take a subscription now simply click here.

And if you're looking for that extra gift for a friend or family member, why not treat them to a theartsdesk.com gift subscription?

more Classical music

Bizet in 150th anniversary year: rich and rare French offerings from Palazzetto Bru Zane

Specialists in French romantic music unveil a treasure trove both live and on disc

Bizet in 150th anniversary year: rich and rare French offerings from Palazzetto Bru Zane

Specialists in French romantic music unveil a treasure trove both live and on disc

Scottish Chamber Orchestra, Ibragimova, Queen’s Hall, Edinburgh review - rarities, novelties and drumrolls

A pity the SCO didn't pick a better showcase for a shining guest artist

Scottish Chamber Orchestra, Ibragimova, Queen’s Hall, Edinburgh review - rarities, novelties and drumrolls

A pity the SCO didn't pick a better showcase for a shining guest artist

Kilsby, Parkes, Sinfonia of London, Wilson, Barbican review - string things zing and sing in expert hands

British masterpieces for strings plus other-worldly tenor and horn - and a muscular rarity

Kilsby, Parkes, Sinfonia of London, Wilson, Barbican review - string things zing and sing in expert hands

British masterpieces for strings plus other-worldly tenor and horn - and a muscular rarity

From Historical to Hip-Hop, Classically Black Music Festival, Kings Place review - a cluster of impressive stars for the future

From quasi-Mozartian elegance to the gritty humour of a kitchen inspection

From Historical to Hip-Hop, Classically Black Music Festival, Kings Place review - a cluster of impressive stars for the future

From quasi-Mozartian elegance to the gritty humour of a kitchen inspection

Shibe, LSO, Adès, Barbican review - gaudy and glorious new music alongside serene Sibelius

Adès’s passion makes persuasive case for the music he loves, both new and old

Shibe, LSO, Adès, Barbican review - gaudy and glorious new music alongside serene Sibelius

Adès’s passion makes persuasive case for the music he loves, both new and old

Anja Mittermüller, Richard Fu, Wigmore Hall review - a glorious hall debut

The Austrian mezzo shines - at the age of 22

Anja Mittermüller, Richard Fu, Wigmore Hall review - a glorious hall debut

The Austrian mezzo shines - at the age of 22

First Person: clarinettist Oliver Pashley on the new horizons of The Hermes Experiment's latest album

Compositions by members of this unusual quartet feature for the first time

First Person: clarinettist Oliver Pashley on the new horizons of The Hermes Experiment's latest album

Compositions by members of this unusual quartet feature for the first time

Gesualdo Passione, Les Arts Florissants, Amala Dior Company, Barbican review - inspired collaboration excavates the music's humanity

At times it was like watching an anarchic religious procession

Gesualdo Passione, Les Arts Florissants, Amala Dior Company, Barbican review - inspired collaboration excavates the music's humanity

At times it was like watching an anarchic religious procession

Classical CDs: Camels, concrete and cabaret

An influential American composer's 90th birthday box, plus British piano concertos and a father-and-son duo

Classical CDs: Camels, concrete and cabaret

An influential American composer's 90th birthday box, plus British piano concertos and a father-and-son duo

Cockerham, Manchester Camerata, Sheen, Martin Harris Centre, Manchester review - re-enacting the dawn of modernism

Two UK premieres added to three miniatures from a seminal event of January 1914

Cockerham, Manchester Camerata, Sheen, Martin Harris Centre, Manchester review - re-enacting the dawn of modernism

Two UK premieres added to three miniatures from a seminal event of January 1914

Kempf, Brno Philharmonic, Davies, Bridgewater Hall, Manchester review - European tradition meets American jazz

Bouncing Czechs enjoy their Gershwin and Brubeck alongside Janáček and Dvořák

Kempf, Brno Philharmonic, Davies, Bridgewater Hall, Manchester review - European tradition meets American jazz

Bouncing Czechs enjoy their Gershwin and Brubeck alongside Janáček and Dvořák

Solomon, OAE, Butt, QEH review - daft Biblical whitewashing with great choruses

Even a top soprano and mezzo can’t make this Handel paean wholly convincing

Solomon, OAE, Butt, QEH review - daft Biblical whitewashing with great choruses

Even a top soprano and mezzo can’t make this Handel paean wholly convincing

Comments

15 pieces on the bill. Not a

A comment such as this

Nevertheless the first

Nevertheless the first question does need some addressing when there are no less than 15 pieces on the programme, don't you think? Especially when you don't need to root around to find excellent choral music by women composers.

‘Most of them were very old