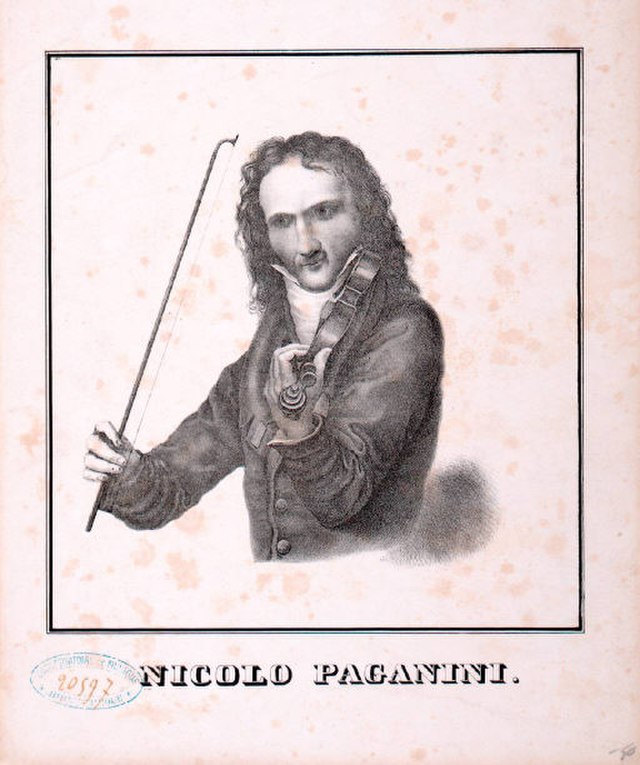

It is taken for granted today that Paganini is almost a God-like figure for violinists. After all, he epitomises the ultimate virtuoso figure, both as someone whose technique outshone (so we are told!) every other player of his time, and who oozed charisma.

That’s the image, one that he carefully cultivated himself, and we know much of it to be true. But how that mythology built to a point where even in somewhere like the Czech Republic – where he had by his standards a terrible failure when he visited – I as a Czech violinist would shape much of my career around the idea of him and dedicate my new album Paganiniana to his influence, is fascinating to try and pin down.

Back in the late 1820s, Paganini performed in Prague several times and, we read, the audiences got smaller and smaller – it definitely was not a case of Paganini-mania, more of the Czech public being underwhelmed by this greatest of classical showmen. And that might have been part of the problem. Prague back then was deeply traditional. Its citizens venerated Mozart and didn’t readily accept the new and groundbreaking (it even took them some time to grow to like Beethoven). So this extraordinary man whose feats were so prodigious and his manner on stage so possessed, that rumours spread that he had either done a deal with the devil, or was a murderer who had practised obsessively during years in prison, might have caused ladies to faint across Europe, but Prague seemed mostly immune.

Back in the late 1820s, Paganini performed in Prague several times and, we read, the audiences got smaller and smaller – it definitely was not a case of Paganini-mania, more of the Czech public being underwhelmed by this greatest of classical showmen. And that might have been part of the problem. Prague back then was deeply traditional. Its citizens venerated Mozart and didn’t readily accept the new and groundbreaking (it even took them some time to grow to like Beethoven). So this extraordinary man whose feats were so prodigious and his manner on stage so possessed, that rumours spread that he had either done a deal with the devil, or was a murderer who had practised obsessively during years in prison, might have caused ladies to faint across Europe, but Prague seemed mostly immune.

Paganini has become centrally important in Czech violin history, though, and Czechia/Bohemia was also important to him, in ways that are sometimes hidden from plain view. To begin with, it was in Prague that Paganini met the German writer Julius Schottky, who went on to write his official biography, documenting lots of important materials in the process. And then there was the Czech violinist, Josef Slavik, who came to be known as "the Bohemian Paganini".

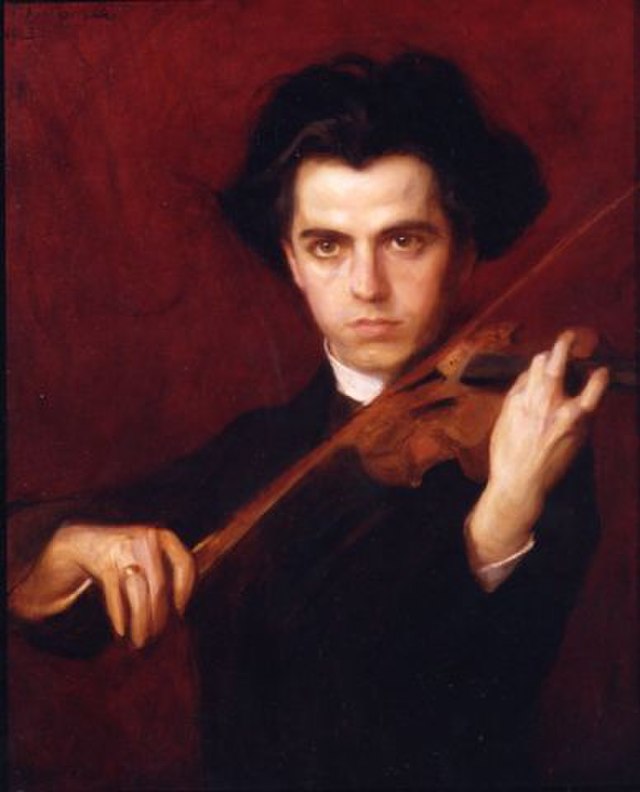

Slavik (pictured left), who lived in Vienna and was deeply influenced by Paganini there, was the first Czech violin virtuoso. The story goes that Slavik heard Paganini play his famous piece "La Campanella" in a concert and, a couple of days later, Slavik knocked on Paganini’s door, introduced himself and played this same "Campanella" off by heart, having only heard it the once. They became friends and even played some concerts together, although, we are told, Paganini never agreed to play duo with Slavik – you have to wonder why.

Slavik (pictured left), who lived in Vienna and was deeply influenced by Paganini there, was the first Czech violin virtuoso. The story goes that Slavik heard Paganini play his famous piece "La Campanella" in a concert and, a couple of days later, Slavik knocked on Paganini’s door, introduced himself and played this same "Campanella" off by heart, having only heard it the once. They became friends and even played some concerts together, although, we are told, Paganini never agreed to play duo with Slavik – you have to wonder why.

Slavik composed pieces very much in the Paganini style, and in fact I have recorded one of these – as a world premiere recording, in fact – on Paganiniana, a devilishly difficult piece that Slavik wrote aged only 17 or 18, and it uses the same kind of technique beloved by Paganini. We must also be grateful to Slavik for sitting nearby while Paganini played and writing down some of his works (Paganini wrote little down as he was notoriously secretive). Many of Slavik’s works are lost today, and he died young, but we can hear through this the kind of impact that Paganini had on some important Czech musicians.

And the same can be said of Heinrich Wilhelm Ernst (pictured right), another violin prodigy from Czech, born in Brno (the second largest city in the Czech Republic), who met Paganini in Vienna. Ernst went all the time to watch Paganini play, to study him, and eventually Paganini encouraged and befriended the younger man. Paganini developed the violin technique which we use today; both Slavik and Ernst adopted it. But what is really incredible to think about is that there were no recordings then, there were no CDs, no Spotify, music wasn’t global. And yet Paganini made such an impact that these other virtuosi were able to study him on stage and learn enough from that to spread what Paganini had invented to other places.

And the same can be said of Heinrich Wilhelm Ernst (pictured right), another violin prodigy from Czech, born in Brno (the second largest city in the Czech Republic), who met Paganini in Vienna. Ernst went all the time to watch Paganini play, to study him, and eventually Paganini encouraged and befriended the younger man. Paganini developed the violin technique which we use today; both Slavik and Ernst adopted it. But what is really incredible to think about is that there were no recordings then, there were no CDs, no Spotify, music wasn’t global. And yet Paganini made such an impact that these other virtuosi were able to study him on stage and learn enough from that to spread what Paganini had invented to other places.

Paganini himself, meanwhile, did little to encourage this – terrified of others learning his secrets, he only ever had one student. In fact, he was an old-fashioned showman in every sense. He would even withhold the sheet music from orchestras with which he played, until the last moment, so that he would sound better in comparison to the musicians around him. And we can see why with someone like Ernst – there were critics at the time who directly compared them, saying that Paganini was the better technician, but Ernst the better musician. Similarly Schubert, who composed his famous Fantasy in C Major for Slavik to play, wrote that Slavik was a second Paganini, only more musical!

Slavik was the first Czech virtuoso, although he was not a superstar back home, but other Czech musicians respected him. And the Czech violin school was developed after Slavik, and so that style of playing was sort of in the tradition of Paganini. I write “sort of” because that style of playing is actually the French style, which had influenced Paganini himself. So the French style, with some awareness of how Paganini had developed it, came to Prague, and the Prague Conservatory is the second-oldest in the world, after Paris. And after Slavik, "the Slav Paganini", many students at the Prague Conservatory talked about Paganini and wanted to play their music using the Paganini technique.

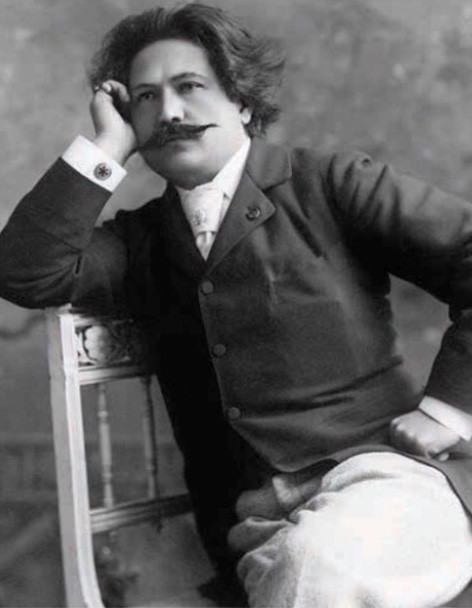

It was the fantastically talented František Ondříček who was the first Czech violinist to go truly international, including to the United States (well, there was also Ferdinand Laub, a close friend of Tchaikovsky). And he would play Paganini’s pieces, write articles about him, and was nicknamed "the second Paganini". He wrote incredibly difficult etudes and other things in Paganini’s style, and he even went to play for Paganini’s son, Achille, in Parma, whose judgement of Ondricek’s playing was to say, “I hear the bow of my father”.

It was the fantastically talented František Ondříček who was the first Czech violinist to go truly international, including to the United States (well, there was also Ferdinand Laub, a close friend of Tchaikovsky). And he would play Paganini’s pieces, write articles about him, and was nicknamed "the second Paganini". He wrote incredibly difficult etudes and other things in Paganini’s style, and he even went to play for Paganini’s son, Achille, in Parma, whose judgement of Ondricek’s playing was to say, “I hear the bow of my father”.

Incidentally, there’s a bit of a grisly end to that story. Achille was so impressed by Ondříček that he had his father’s crypt opened and removed his coffin so that Ondříček could see Paganini’s face through a little window in the coffin, and as they were replacing it, a nail fell from the coffin and Ondříček was allowed to take it. He wrote later that this way he had “met” Paganini, and about how moved he had been, and he kept that nail in his violin case until the day he died and was himself buried with it.

After Ondříček came Jan Kubelík, father of the conductor Rafael Kubelík and a superstar violinist in his time, eclipsing even František Ondříček. They called Kubelík – you guessed it – also "the second Paganini", or sometimes "Paganini reborn". Commentators of the time wrote about the mesmerising Paganini-like look in Kubelik’s eyes; people fainted in his concerts just like at Paganini’s. At one Kubelík concert in Russia a fan of his actually shot himself because he couldn't bear the excitement of the concert.

So the newspapers all around the world really pushed this idea of the Kubelík-Paganini connection, and while Kubelík was not a born self-publicist like his famous predecessor and didn’t push that line, he did love Paganini’s music, often played it in concert and even composed a cadenza for Paganini’s Violin Concerto No. 1 (which I also include in this new album).

Kubelík was the biggest violin superstar in the world before World War One. He was one of the first European violinists to tour to India; he was celebrated in Japan; he had eight huge tours in the United States; he even had a train carriage named after his estate, Bychory, which he would take on tour with him. And when he came to New York the harbour would be lined with thousands of people waving and yelling, “Long live Kubelík!”. In many ways he really was the closest to Paganini that the world had seen, and of course he and all of the others propagated the legend of Paganini as they went.

Kubelík was the biggest violin superstar in the world before World War One. He was one of the first European violinists to tour to India; he was celebrated in Japan; he had eight huge tours in the United States; he even had a train carriage named after his estate, Bychory, which he would take on tour with him. And when he came to New York the harbour would be lined with thousands of people waving and yelling, “Long live Kubelík!”. In many ways he really was the closest to Paganini that the world had seen, and of course he and all of the others propagated the legend of Paganini as they went.

And then it all stopped for Kubelík. World War One came, travel became much harder and as a Czech with an estate on the Austrian-Hungarian border, Kubelík found himself in a tricky position politically. It led him into deep debt, his career never recovered, and in the meantime Fritz Kreisler had taken his place in global popularity.

After Kubelík, the Paganini myth was greatly diminished. Kreisler was the man of the moment and he was very different: first and foremost people appreciated his beauty of tone, not his technical acrobatics. In the Czech Republic, musicians started to talk much more about musicianship over technique; not that Paganini became a dirty word, but his status dimmed. Most of the leading violinists, with one or two exceptions (Váša Příhoda being one), rarely played him – Suk never played Paganini, for instance.

So I have consciously spent much of my career working to bring Paganini back to the centre of the Czech violin tradition. In terms of respect for virtuoso violin playing, and also the idea that classical music doesn’t always have to be played with a frown. After Kreisler, Czech musicians began to venerate great musicians like David Oistrakh and Isaac Stern – very important players in many ways, of course – and a sense began to permeate that classical music always has to be very serious. In fact, the phrase that the Czech newspapers use for classical music more precisely translates as "serious music". And some of that had to do with the seriousness of the communist era when we were under the Russians.

So I have consciously spent much of my career working to bring Paganini back to the centre of the Czech violin tradition. In terms of respect for virtuoso violin playing, and also the idea that classical music doesn’t always have to be played with a frown. After Kreisler, Czech musicians began to venerate great musicians like David Oistrakh and Isaac Stern – very important players in many ways, of course – and a sense began to permeate that classical music always has to be very serious. In fact, the phrase that the Czech newspapers use for classical music more precisely translates as "serious music". And some of that had to do with the seriousness of the communist era when we were under the Russians.

Either way, with the diminishing of the Paganini legend, something changed. So I am trying to be one of the ones to try to change it back, to bring back some of what Paganini gave us; with the music and the sense that music can be played to be fun and to take your breath away. And this, my album in which I play solo violin works by many composers from around the world who were inspired by Paganini (including pieces by many of the violinists I have mentioned in this article, and one work by myself), is one more part of my contribution. Raise a glass to Paganini, and while we’re at it to Slavik, Ondříček, Kubelík and all the rest.

Add comment