To demonstrate what makes chamber masterpieces tick and then to play them, brilliantly, is a sequence which ought to happen more often. Perhaps too many musicians think their eloquence is confined to their instruments. Not violinist Simon Blendis and pianist William Howard of the Schubert Ensemble. Both are models of naturalness, witty when occasion demands, fearless of chapter and verse when they can conjure up the sounds of what they're talking about, never needing to do the "we're passionate about this music" shtick when it's perfectly obvious, and will become more so in performance.

In little over half an hour they evoked spot-on illustrations of Martinů's cross-rhythms, syncopated dances and proto-minimalism in his Second Piano Quintet of 1944, and of the shifting colours beneath the cornucopia of melody, the subtle ongoing development and the unusual ranges for the instruments in his fellow Czech Dvořák's fertile A major Piano Quintet. When it came to the performances after a ten-minute interval, we heard all this and more in performances of an intensity for which the mere demonstrations hadn't prepared us. Earlier comparisons of the range in which Dvořák sets the cello's opening melody with what it would sound like an octave above and below made us listen out for the composer's equal genius in picking unusual ranges for themes in the other instruments; Jane Salmon's cello, Douglas Paterson's viola and Blendis's often very high-lying violin part all sounded so free and natural, yet at the same time unorthodox, in the liberating acoustic of Kings Place's Hall One, the best venue in London for chamber music.

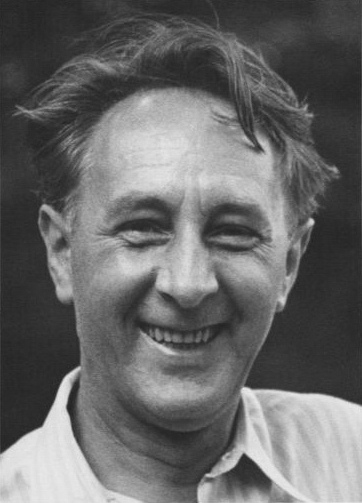

We needed the Dvořák to take us from the bittersweet, major-minor fluctuations of its mostly vibrant first movement and the poetic shifts between the Dumka-lament and what Blendis had described as the calypso joyousness of its first contrasting episode to the unalloyed happiness of Furiant-Scherzo and Finale. Because, like Dvořák's first half but to the power of ten, Martinů's masterpiece is in a constant state of febrile evolution. Anthony Burton in his excellent notes hits the quality on the head by describing the sequencing of the first movement – and by extension nearly everything by Martinů in American exile from his beloved Moravia (the composer pictured above in 1943, the year before he composed the Second Piano Quintet) – as "owing nothing to the organic development or the tonal logic of traditional sonata form, and everything to a sense of psychological rightness".

We needed the Dvořák to take us from the bittersweet, major-minor fluctuations of its mostly vibrant first movement and the poetic shifts between the Dumka-lament and what Blendis had described as the calypso joyousness of its first contrasting episode to the unalloyed happiness of Furiant-Scherzo and Finale. Because, like Dvořák's first half but to the power of ten, Martinů's masterpiece is in a constant state of febrile evolution. Anthony Burton in his excellent notes hits the quality on the head by describing the sequencing of the first movement – and by extension nearly everything by Martinů in American exile from his beloved Moravia (the composer pictured above in 1943, the year before he composed the Second Piano Quintet) – as "owing nothing to the organic development or the tonal logic of traditional sonata form, and everything to a sense of psychological rightness".

To penetrate it, though, takes intensive hard work, and the Schubert Ensemble, Martinů pioneers, have gone well below the surface. So they can bring tears to the eyes and put you on the rack with the sudden bursts of expansive emotion – usually, as Blendis had pointed out, for the strings alone, the piano mostly driving them forward in semi-demented menace or joy. Howard's touch was even and assured throughout, never mechanical, and the team ran the gamut from elegant neo-baroque trills in the outer portions of the Adagio movement to the merry-go-round delirium which spins the outer movements to surprisingly optimistic conclusions. Exhausting, surely for the players; an emotional roller-coaster for the audience.

Gratitude to the players for championing one of those rare things which are often mooted but rarely deliver like this, a neglected masterpiece, came with a sadness that this was not only the last of their six "Quintessentials" concerts this season – kicking myself for missing the rest – but their final concert in Kings Place, with which thanks to the presiding genius Peter Millican they have had an association dating back to before the hall's opening events nine years ago. After 35 years together, they bow out conclusively in June 2018; so don't miss their Wigmore finale next March.

Add comment