Horn concertos don't make frequent appearances in the standard concert repertory and when they do it will usually be a work by Mozart or Richard Strauss. It wouldn't be entirely true to say that horn players feel keenly the lack of a serious core of works such as that available to pianists, string players and singers. This is partly because of the wealth of sumptuous orchestral writing which allows the horn to shine from the back of the orchestra at key moments without requiring it to carry the entire performance, and also owing to the small number of significant solo works by some great composers.

The concertos for solo horn and orchestra by Mozart fall into this latter category, although not all are as familiar to audiences as (the wrongly numbered) No 4 (K495) of Flanders and Swann "An Ill Wind" fame. As with so many classical concertos most of them came from a particular composer/performer relationship, the performer in this case being one Joseph Leitgeb (1732-1811), a renowned player of his time, about whom very little is really known aside from some accounts in Mozart's letters and a few appearances in registers and some practical documents which he left behind. (Pictured below, Roger Montgomery)

Leitgeb (also known as Leutgeb) appears in the register of Esterhazy Court employees in 1763 (where Joseph Haydn was employed), and it is almost certain that Haydn wrote his Horn Concerto in D for Leitgeb. In the early 1760s he performed concertos in the Vienna Burgtheater by M. Haydn, Ditttersdorf and Hofmaster. He also travelled to Paris where the Mercure de France praised his playing in two of the 1770 Concerts Spirituels citing his outstanding quality as being "able to 'sing' adagios as perfectly as the most mellow, most interesting and most accurately pitched voice".

Leitgeb (also known as Leutgeb) appears in the register of Esterhazy Court employees in 1763 (where Joseph Haydn was employed), and it is almost certain that Haydn wrote his Horn Concerto in D for Leitgeb. In the early 1760s he performed concertos in the Vienna Burgtheater by M. Haydn, Ditttersdorf and Hofmaster. He also travelled to Paris where the Mercure de France praised his playing in two of the 1770 Concerts Spirituels citing his outstanding quality as being "able to 'sing' adagios as perfectly as the most mellow, most interesting and most accurately pitched voice".

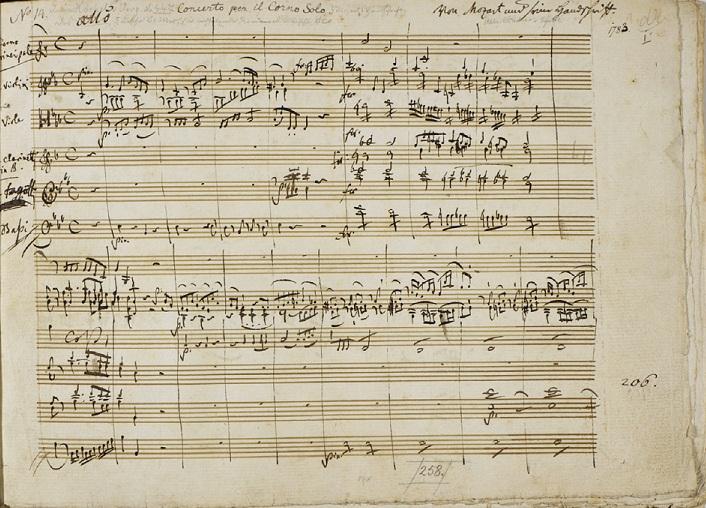

He appeared many times in Mozart junior and senior's letters, initially when the young Wolfgang, away on the first European Grand Tour in 1763, listed Leitgeb among those whom he missed. On one of his Italian tours with his father he frequently beseeched Leitgeb to join them that he might make his fortune and Leitgeb did eventually tour with them in 1773. (On this evidence it appears that the revision to include the horn obbligato aria in Mitridate, Re di Ponte was intended for him but that he may not have arrived in time to deliver it). Leopold Mozart wrote to Wolfgang in 1777 that he had loaned Leitgeb the money to purchase a tiny house in Vienna and forwarded the request for him to write a horn concerto. This concerto took a long time to come but finally in 1783 it arrived with the headnote "WA Mozart took pity on Leitgeb, Ox, Ass and Fool at Vienna, May 27th 1783". There followed another three "Leitgeb" concertos, K495 in 1786, K447 in 1787 and finally the unfinished K412/514 in 1791. There was further evidence of personal interaction verging on playful banter in these works, particularly the last where a continuous running commentary becomes more and more raucous. Even in Mozart's last year he remained close to his friend, taking him to performances of The Magic Flute and staying with the Leitgebs when his wife was away for a health cure.

In the context of Mozart's works the number of horn concertos is slight next to the piano concertos, roughly on a par with the violin concertos and exceeds the single clarinet concerto, oboe concerto, bassoon concerto and the two flute concertos. In the canon of horn music they occupy a much greater place than this assessment suggests owing to the dearth of really good horn music by first-rate composers. In the development of the instrument and the concerto they are also hugely significant. Although there are many solo horn concertos which predate Mozart's concertos and which also use the three-movement form culminating in a compound-time rondo, there are no compositions which are so complex harmonically or use quite such chromatic passages in the solo horn part.

Watch Roger Montgomery playing and talking about Mozart's Horn Concerto No 4

Until this point horn parts largely concentrated on the available notes of the natural series of harmonics which means that the parts are triadic in the low and middle registers and can play scales in the highest octave, only becoming fully chromatic at the very top. The "discovery" that the varied placement of the right hand in the bell of the instrument could allow most of the gaps to be bridged was claimed by Domnich for his teacher Anton Hampel from the Dresden Court in the mid-18th century, but is likely to have been widely known and used for much longer.

Leitgeb was clearly a master of the stopping technique as Mozart, when he wrote his first works for him, employed many such stopped notes in lyrical sections and passagework. This had the effect of not only unlocking the middle register but allowing the horn to move through more remote key areas than it had hitherto been able to. In effect the horn could now participate very much more fully in the more tonally complex forms and structures. This gain comes with a comparative loss of tone on the notes which have to be modified, and a great deal of effort needs to be employed to preserve the musical line which is now full of subtly disparate tones by compensating the dynamics and bending the pitches to correct them. One by-product of this constant adjustment is that the dynamic has to be maintained at a level where the different sounds can be suitably blended: too much projection in too remote a key and there is a strong possibility that the stopped notes will stick out with a metallic sound; too quiet and they will be overly muffled.

It is apparent from the extent of Mozart's lyrical writing and the technical demands he requires that Leitgeb's abilities were not exaggerated. He possessed a wide range but seemed to favour upwards runs in the high register rather than the leaping arpeggios which were more the signature of another great horn virtuoso, Giovanni Punto (1746-1803) (pictured below). Sadly there exists no contemporary account of the performances of these works. The surviving manuscript folios and various passages from Mozart's letters show an affectionate and bawdy relationship full of banter, and this aspect has sometimes been exaggerated. While there are many jokes and jibes on the written face of the score, little of this is obvious from the actual music itself which is mostly far from slapstick or tongue-in-cheek.

It is apparent from the extent of Mozart's lyrical writing and the technical demands he requires that Leitgeb's abilities were not exaggerated. He possessed a wide range but seemed to favour upwards runs in the high register rather than the leaping arpeggios which were more the signature of another great horn virtuoso, Giovanni Punto (1746-1803) (pictured below). Sadly there exists no contemporary account of the performances of these works. The surviving manuscript folios and various passages from Mozart's letters show an affectionate and bawdy relationship full of banter, and this aspect has sometimes been exaggerated. While there are many jokes and jibes on the written face of the score, little of this is obvious from the actual music itself which is mostly far from slapstick or tongue-in-cheek.

Musically, they might not impress next to the language and scale of the piano concertos, but the ingenuity with which Mozart crafts a large-scale form with a newly discovered tonal palette brought the solo horn genre away from the simpler formula of the reliance on the natural open notes and consequently into a richer and more complex area. It is quite easy to take them for granted now, especially as there are more recent "great" works, but they remain more than just a record of a friendship and an expert understanding of the technical possibilities of a simple form of the horn.....especially to horn players!

These differences are particularly relevant when attempting reconstructions of incomplete Mozart horn works as the scale, form and mood of many of Mozart's concertos for other instruments are so specifically conceived for those instruments that they offer few clues in the completion of the horn works.

The fragment in E major is one of Mozart's most tantalising legacies to horn players. Composed in either 1785 or 1786 it falls after his first concerto for Leitgeb (K417 in 1783) but probably before the second one (K495 in 1786) and his intentions were never clear for the piece. Only one of the horn concertos is complete in manuscript, that of K447 in E flat, but while full versions of others are facilitated by early editions, this one, K494a, is discontinued, abandoned after a mere 90 bars with a (mostly) fully orchestrated tutti and a sparingly sketched solo exposition which stops just short of the second subject. While there is no dedication to a particular soloist, it is possible that it was intended for Leitgeb, but there is an absence of the playful commentary which can be found somewhere in all of the Leitgeb works. Mozart was in the habit of signing and dating his works upon completion, so the abandonment deprives us of any such specific information. It could be for another player or perhaps it was abandoned before such comments might have been overlaid.

The fragment in E major is one of Mozart's most tantalising legacies to horn players. Composed in either 1785 or 1786 it falls after his first concerto for Leitgeb (K417 in 1783) but probably before the second one (K495 in 1786) and his intentions were never clear for the piece. Only one of the horn concertos is complete in manuscript, that of K447 in E flat, but while full versions of others are facilitated by early editions, this one, K494a, is discontinued, abandoned after a mere 90 bars with a (mostly) fully orchestrated tutti and a sparingly sketched solo exposition which stops just short of the second subject. While there is no dedication to a particular soloist, it is possible that it was intended for Leitgeb, but there is an absence of the playful commentary which can be found somewhere in all of the Leitgeb works. Mozart was in the habit of signing and dating his works upon completion, so the abandonment deprives us of any such specific information. It could be for another player or perhaps it was abandoned before such comments might have been overlaid.

As to the reason for the failure to complete, one can only speculate. Mozart was not given to writing for posterity and if a certain opportunity for a performance vanished, he was not averse to ditching a piece mid-composition. However, the works written for Leitgeb were not revenue producers for him and seem to have been created from friendship rather than any commercial imperative. This could suggest that the piece was intended for another virtuoso such as Giovanni Punto or Jacob Eisen if change of circumstances were indeed a factor. The work itself is slightly unusual in its key of E major, not so much for any extra difficulties which might be presented to the horn, but for the rather tricky problems presented to the orchestral instruments. There are remarkably few works by Mozart which are principally in E. Exceptions are the Piano Trio K542 and the Adagio K261 for violin and orchestra, but otherwise it is mainly encountered in operatic movements such as "Soave sia il vento" and "Per pietà" from Cosi and "Placido è il mar" from Idomeneo or examples like the second movement of the Violin Concerto in A K219.

As to the reason for the failure to complete, one can only speculate. Mozart was not given to writing for posterity and if a certain opportunity for a performance vanished, he was not averse to ditching a piece mid-composition. However, the works written for Leitgeb were not revenue producers for him and seem to have been created from friendship rather than any commercial imperative. This could suggest that the piece was intended for another virtuoso such as Giovanni Punto or Jacob Eisen if change of circumstances were indeed a factor. The work itself is slightly unusual in its key of E major, not so much for any extra difficulties which might be presented to the horn, but for the rather tricky problems presented to the orchestral instruments. There are remarkably few works by Mozart which are principally in E. Exceptions are the Piano Trio K542 and the Adagio K261 for violin and orchestra, but otherwise it is mainly encountered in operatic movements such as "Soave sia il vento" and "Per pietà" from Cosi and "Placido è il mar" from Idomeneo or examples like the second movement of the Violin Concerto in A K219.

Any issues with continuing and completing this work lie not in the treatment of the thematic material which Mozart has outlined sufficiently to be able to create a plausible exposition and recapitulation, but in the middle section (which always replaces the traditional development in the horn concertos) where new lyrical material is usually introduced as opposed to the more rigorous treatment of previous thematic material. While the existing horn concertos serve as models for these episodes, the challenge is to use the templates without copying and to adapt material freely without exceeding the simple style which Mozart employed so effortlessly.

- Roger Montgomery's new recording of the four completed Mozart horn concertos with the OAE is available on Signum Classics. Read Graham Rickson's review

- The autograph manuscript of K447 is in the Stefan Zweig Collection at the British Library. The digitised score can be viewed online. All the British Library's Mozart manuscripts are online.

Add comment